Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (French:

Tintin au pays des Soviets)Original publication dates: January 1929 – May 1930

First collected edition: 1930

Author: Hergé

Tintin visits: Belgium (Brussels), Germany (Berlin), Soviet Union (Moscow, Belarus, Stolbtsy), Poland (Second Polish Republic)

Overall rating:

Plot summary available here

Plot summary available here.

Publisher's synopsis:

Accompanied by his dog Snowy, Tintin leaves Brussels to go undercover in Soviet Russia. His attempts to research his story are put to the test by the Bolsheviks and Moscow's secret police...Comments: This first Tintin adventure initially saw publication in the pages of the children's supplement of

Le Vingtième Siècle ("The Twentieth Century"), a right-wing and staunchly Catholic Belgian newspaper, run by Abbot Norbert Wallez. Wallez intended to use the supplement, which was named

Le Petit Vingtième ("The Little Twentieth"), as a means of passing on his conservative and pro-fascist ideals to the paper's young readership. The 22-year-old Hergé (real name Georges Remi), who already worked as an illustrator for the newspaper, was appointed to the position of editor of

Le Petit Vingtième in 1928. After illustrating a number of different strips for the supplement, Hergé finally got a chance to write and draw his own creation, Tintin. I've read that

Tintin in the Land of the Soviets represents the earliest example of an American-style comic strip, with speech balloons and the like, appearing in Europe. I've no idea if that's actually true, but clearly, having been published in 1929, it would have to be one of the very earliest examples, I would think.

Although both the writing and artwork in this first Tintin adventure are undeniably crude when compared to Hergé's later works, the basic personalities and character of Tintin and his white-haired terrier, Snowy, are more or less fully formed from the start. For example, Tintin is sporting his distinctive plus-fours (golfing trousers) and unruly quiff of hair from the very first page...

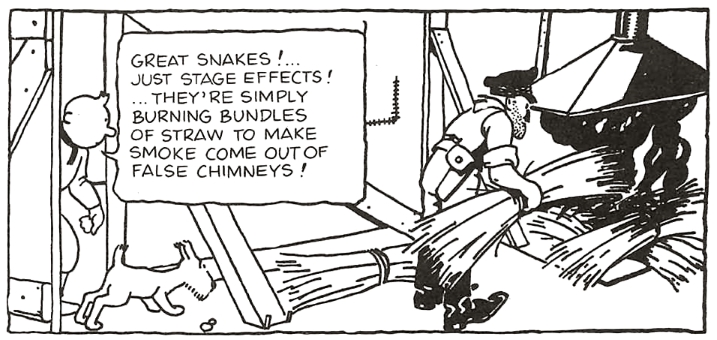

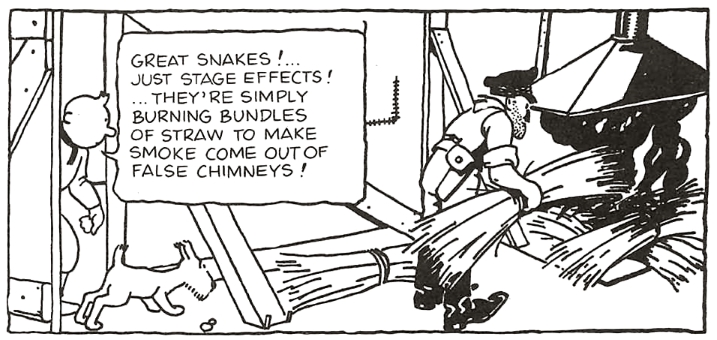

Then, just a little later on in the story, we hear the boy reporter utter his catchphrase of "Great Snakes!" for the first time...

I should just note though that Tintin's signature exclamation is a creation of the English translators, Michael Turner and Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper, and is not present in the original French language editions of the books.

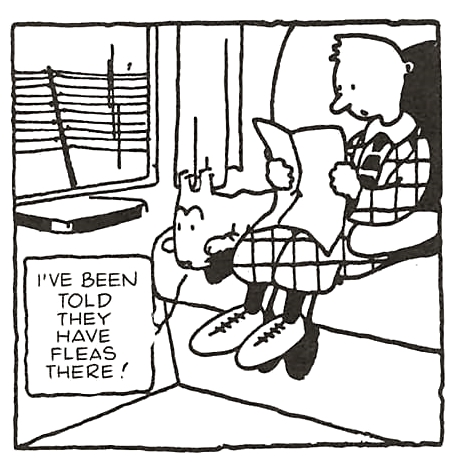

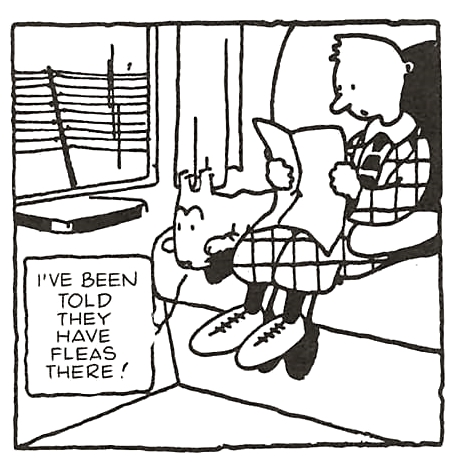

The basics of Snowy's personality are similarly well defined: he's shown to be Tintin's unerringly loyal sidekick, a source of comic relief, with an obsession for bones and a susceptibility towards vanity. He can understand human speech too. He also serves as a welcome foil to the boy reporter's unswerving optimism, by offering up sarcastic and cynical rejoiners.

I suppose at this point I should just offer an explanation of the term "boy reporter". Tintin is not a child. He works for a newspaper as an investigative journalist and he can drive a car and fly a plane. Although his age is never explicitly stated by Hergé, he is, in all likelihood, in his late teens. The concept of being a "teenager" was unheard of when these earliest Tintin stories were written. Back then, most people would leave school at around the age of 14 and go straight out to work, essentially transitioning from a child to an adult almost overnight. Young males were routinely referred to in the workplace as "boy" or "lad" by their older co-workers, and this is essentially why Tintin is referred to as a boy reporter, despite the fact that, in my mind, he's probably between 17 and 19. On a related note, it's interesting that we get to see Tintin working like a real reporter in

Land of the Soviets and actually composing a piece for his newspaper. This would be the first and last time that such a thing would happen in the series.

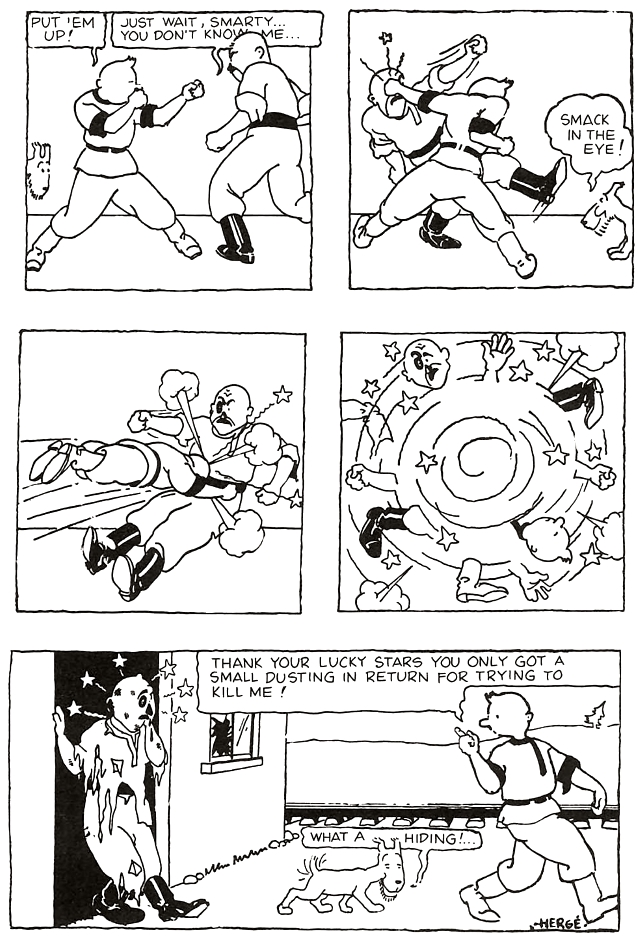

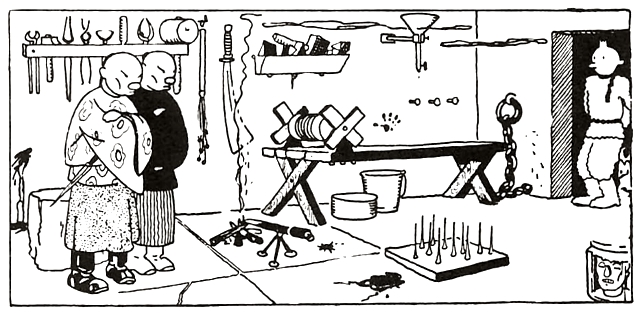

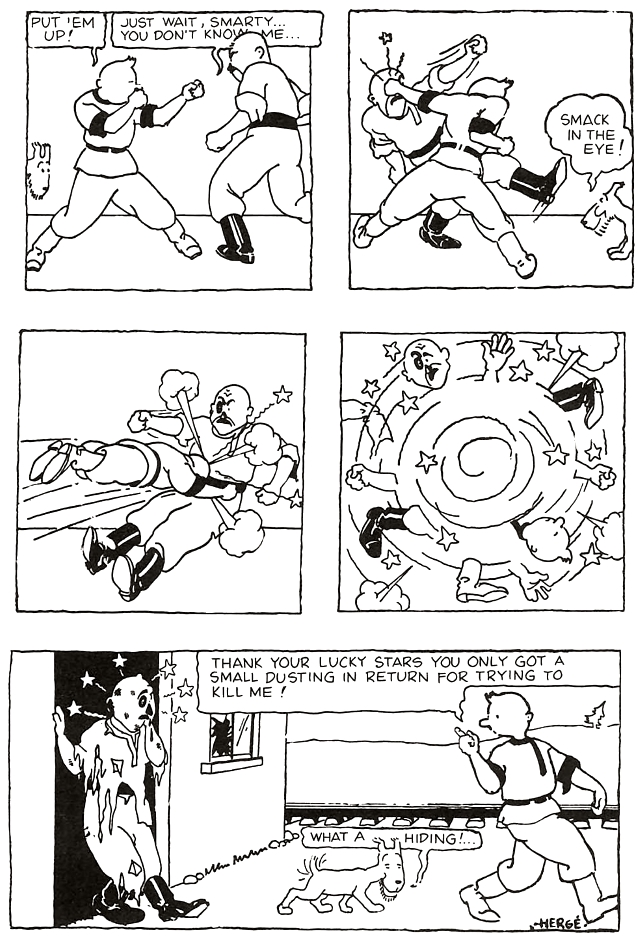

While we're on the subject of Tintin's age, he's shown here to be pretty tasty in a punch-up for one of such tender years. In fact, he's quite the pugilist in this adventure, as you can see...

In fact, Tintin comes across as rather thuggish in this first story. His tendency towards violence reaches new heights when he kicks the cr*p out of a wild bear about two thirds of the way through the adventure. To be fair, the bear was just about to eat poor Snowy, but still, this scene neatly foreshadows the unsavoury predilection for animal cruelty that Tintin displays in his next adventure,

Tintin in the Congo.

Without doubt, the biggest problem with

Land of the Soviets – aside from its crudely rendered artwork, which is almost totally bereft of the detailed backgrounds and meticulous authenticity that Hergé would later justly become famous for – is its heavy-handedness. The book is little more than a piece of anti-communist propaganda, and not a particularly well crafted one either! The Soviet authorities are universally portrayed as stupid, evil, corrupt, and viciously cruel. Unfortunately, in order to put across Wallez's anti-Bolshevik sentiments in the strip, Hergé has to have Tintin condescendingly point out the communists' failings at every opportunity, which, in turn, serves to imbue our hero with an off-putting air of smugness and self-righteousness.

Oh, and we also get some offensive racial stereotyping of the Chinese thrown in for good measure...

No wonder Hergé later described this book, along with

Tintin in the Congo, as "the sins of my youth."

Another criticism of this story would be that it is far too episodic in nature, as we watch Tintin go from one action sequence and communist put-down to another in rapid succession, with little in the way of any over-arching plot. Of course, given its origin as a weekly comic serial, this is somewhat understandable, but I've also read that while he was writing

Land of the Soviets, Hergé had little or no idea of where the adventure was supposed to be going and it shows.

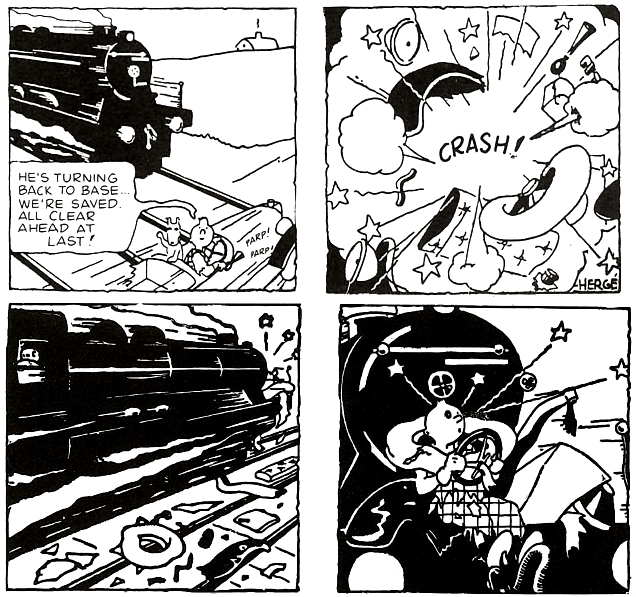

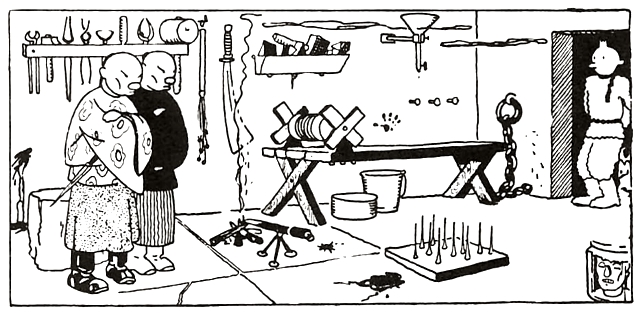

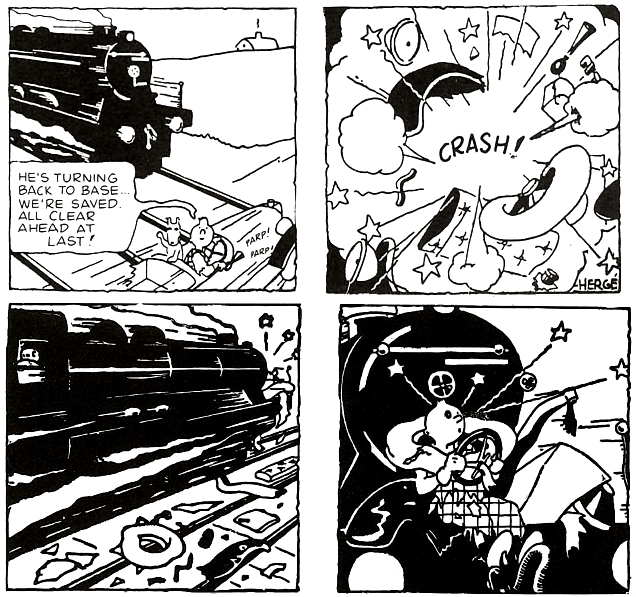

There's a lot of cartoonish, slapstick physical humour and unrealistic violence in this story too, which is very much at odds with later books in the series. Here, Tintin is routinely involved in lethal incidents that should have, by rights, killed him – such as when his car collides with a steam train, leaving him perched on the front of the engine...

Unfortunately, the slapstick comedy here simply isn't very funny and, I'm pleased to say, Hergé would get much better at eliciting full belly laughs with physical comedy in subsequent stories.

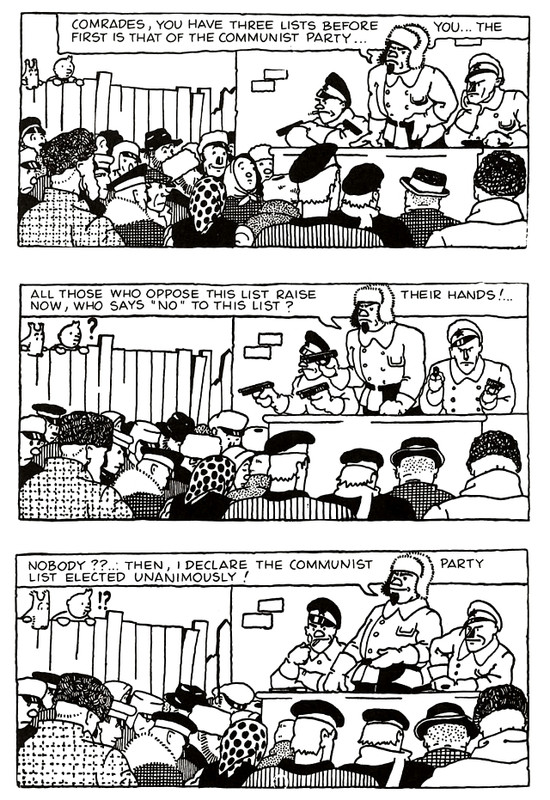

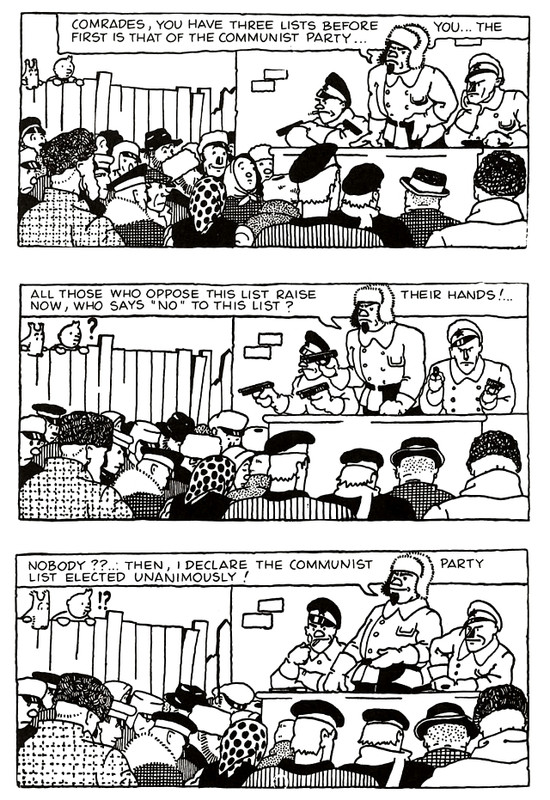

In spite of this book's shortcomings, there are faint glimpses of the greatness yet to come. For example, there's a well executed split-view sequence, in which we see a group of Soviet officials attempting to enter Tintin's room from the corridor outside, that is quite well staged. Then there's this scene, in which Tintin witnesses a group of peasants being coerced at gunpoint into voting for the communist party, which is fairly powerful...

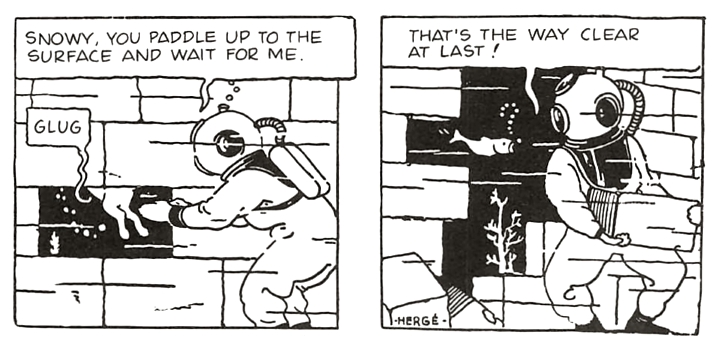

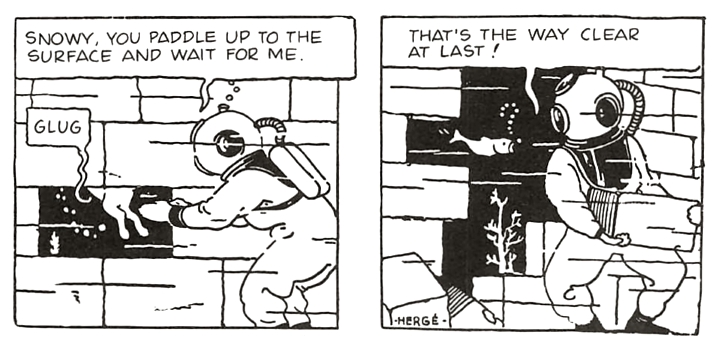

Additionally, the scene in which Tintin dons an old fashioned diving suit exhibits a confidence of line that is sadly lacking from much of the rest of

Land of the Soviets. It also brings to mind similar scenes from the twelth book of the series,

Red Rackham's Treasure...

The depiction of the Gare du Nord in Brussels on the final page – as Tintin and Snowy return home to cheering crowds, having foiled a Bolshevik plot to blow up the capitals of Europe – is simply excellent and is rendered with an accuracy that is noticeably lacking elsewhere in the book. This kind of attention to detail and authenticity would soon become a hallmark of Hergé's art...

Overall, as the opening salvo of one of the greatest

bandes dessinée series of all-time,

Tintin in the Land of the Soviets is a misfire of epic proportions. It is, without doubt, the weakest of all 24

Tintin stories, but thankfully it's a rather quick read. In addition to the aforementioned scratchy, sketch-like artwork and two-dimensional anti-communist writing, a lot of this book is just really silly and much less realistic than later entries in the series. I mean, at one point Tintin fashions a makeshift propeller for his aeroplane out of a nearby tree. Now, clearly propellers have to be aerodynamically machined to specific measurements in order to work, not just roughly whittled from a log with a penknife, but Hergé doesn't let that stop the boy reporter. Such disregard for realism and science would be firmly out of favour in later books.

Still, for all of its shortcomings, a number of the basic pillars on which The Adventures of Tintin are built are already in place here. Tintin already has his distinctive trousers and hairstyle; he is shown to be a reporter for a Belgian newspaper; he is a champion of the oppressed; he adopts cunning disguises on occasion; and his dog, Snowy, provides comic relief and wry commentary. That said, Hergé is still clearly trying to decide exactly what sort of a character Tintin will be.

It's also important to remember that Hergé himself was very ashamed of this book. In fact, he was so ashamed that he actively prevented its republication until 1973. For that reason, it is the only one of his early Tintin adventures that Hergé didn't redraw in later years, which is why it's only available in its original 1930 version today. Still, the strip was an immediate success with the children of Belgium upon publication, ensuring that there would be further adventures for the boy reporter, and, for that, we should be grateful.

Although this is the first Tintin adventure, I would

not recommend it to newcomers to the series. This book is for hardcore Tintinologists only. If you are a new reader, you would be far better off starting with the third book,

Tintin in America, or any of the volumes that followed it. Still, to a lover of the Tintin series, this is the acorn from which a mighty oak tree would grow.