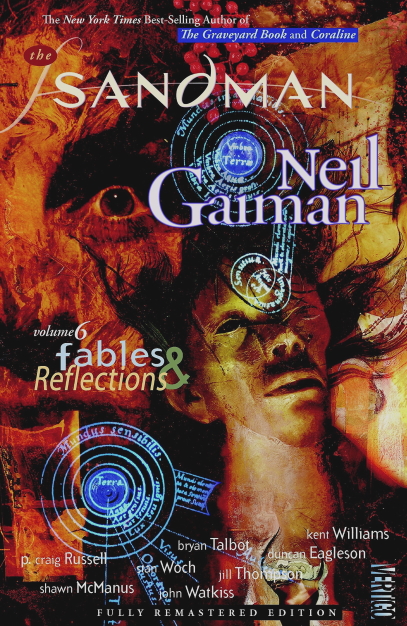

The Sandman: Volume 6 – Fables & ReflectionsOriginal publication:

The Sandman #29–31 (August – October 1991) /

The Sandman #38–40 (June 1992 – August 1992) /

Vertigo Preview #1 (February 1993) /

The Sandman #50 (June 1993)

Script: Neil Gaiman

Artwork: Kent Williams (pencils & inks)/Shawn McManus (pencils & inks)/Stan Woch (pencils & inks)/Dick Giordano (inks)/Duncan Eagleson (pencils)/Vince Locke (inks)/Bryan Talbot (pencils)/John Watkiss (pencils & inks)/Mark Buckingham (inks)/Jill Thompson (pencils)/P. Craig Russell (pencils & inks)

Publisher's synopsis

Publisher's synopsis:

The critically acclaimed The Sandman: Fables and Reflections continues the fantastical epic of Morpheus, the King of Dreams, as he observes and interacts with an odd assortment of historical and fictional characters throughout time. Featuring tales of kings, explorers, spies and werewolves, this book of myth and imagination delves into the dark dreams of Augustus Caesar, Marco Polo, Cain and Abel, Norton I and Orpheus to illustrate the effects that these subconscious musings have had on the course of history and mankind.So, I'm onto volume 6 of my read-through of

The Sandman.

Like the earlier volume "Dream Country", this is a collection of done-in-one stories and other odds and ends in which Neil Gaiman takes us on a sort of hodgepodge journey through history and folklore. Four of the tales ("Thermidor", "Three Septembers and a January", "August", and "Ramadan") are about prominent historical figures from different eras and different parts of the world, who all apparently led lives that were influenced by dreams. The other stories focus on folklore, Greek mythology, fear of creative failure, and the physical act of storytelling. Actually, storytelling is one of the repeating motifs in this collection, though that's not really a new thing for this series.

The issues of

The Sandman included here are gathered together out of sequence from their original chronological publishing order, and, like the earlier "Dream Country", many of them don't actually feature the title's central protagonist Dream (a.k.a. Morpheus) in much more than a supporting role. However, whereas that earlier collection of one-shots was of such high quality that the lack of Morpheus didn't really matter too much, "Fables & Reflections" isn't quite as satisfying on the whole.

Anyway, let's focus in on each of the stories included in this volume...

Fear of FallingThis short story appeared in

Vertigo Preview #1, which I think was a publication intended to officially launch DC's Vertigo line of comics. The comic featured a number of exclusive stories from DC's then-current crop of "for mature readers" titles, including, of course,

The Sandman.

"Fear of Falling" provides

Fables & Reflections with a really strong start: by page 2, I was already thinking, "Holy s**t, this is good!" But like any fiction, so much of what makes it work or not work for a reader boils down to what they themselves bring to it, in terms of their personality, emotional state, life experiences, and general world-view. Like the earlier "Calliope", this is a story that deals with the insecurities and nagging doubts that gnaw at creative people, and I can definitely relate to that.

In this case, the creative in question is a young playwright who is about to debut his newest play. As rehearsals continue and the opening night draws nearer, he begins to become anxious about the possibility of his play being badly received by audiences and critics. His fear of failure (the metaphorical fear of falling referenced in the title) becomes so overwhelming that he makes the decision to stop rehearsals and abandon his play altogether. However, after falling asleep in front of his TV watching Alfred Hitchcock's

Vertigo (I see what you did there Gaiman

), he encounters Dream, who offers some sage advice about the possible futures that are open to a person who is falling in their dreams: sometimes they wake, sometimes they die, and sometimes...just sometimes...they fly! The young playwright's resulting epiphany gives him the courage to press on with rehearsals.

Interestingly, we never actually see the play premièred or find out whether or not it was a success, but those concerns are really beside the point. The message here is that in order to achieve anything of worth we have to have the courage to attempt to fly, even if there's the possibility that we will fall. There is, however, a secondary point being made: as well as the fear of failure, there's also the fear of success and the additional pressures and insecurities that it brings. After all, the higher you climb, the further you have to fall, right?

"Fear of Falling" is a short and simplistic tale, but it's a well written one. Kent Williams' artwork isn't really to my tastes – it's too scratchy and scribbly – but it serves the brief narrative well enough. Really though, it's the dialogue that sells the story for me. Gaiman's scripting is very naturalistic, conjuring entirely relatable characters in just a few panels, which is no mean feat.

Three Septembers and a JanuaryThe next story concerns one Joshua Norton of San Francisco, who, in 1859, proclaimed himself Emperor of the United States of America. Norton actually existed and I believe that I'd heard about him before (something in my distant memory was jogged when I read this story). I read up on him online after finishing this issue and the particulars of his life are fascinating. Norton was once a wealthy businessman, but he lost his fortune after investing in Peruvian rice. He then fell into depression and obscurity, resurfacing in 1859 to declare himself Emperor. Though he wielded no political power at all, and was widely viewed as mentally deranged or at least wildly eccentric by the people of San Franscisco, they nonetheless took him to their bosom. He was treated as a celebrity and something of a beloved curiosity around the city.

The story opens with the dejected and miserable Norton, his business now in tatters, contemplating suicide, while Dream's sister Despair looks on. She issues Dream with a challenge to try and save him from her clutches using his dream powers. Reluctantly Dream agrees and plants the notion of becoming the first Emperor of the U.S. in the depressed businessman's mind while he sleeps. The next day, Norton, with renewed purpose in his life, writes a letter to a local newspaper announcing his proclamation to the world. The paper runs the letter as a joke, but the story catches the public's imagination and the rest is history!

I think Gaiman's message here is all about the powerful role that imagination plays in forming our identities, and how the way in which we present ourselves to the world at large crystallises that identity for ourselves and those around us. The point being that, if you proclaim yourself as something forcefully enough, other people will eventually come to view you in that way and treat you as that thing, regardless of whether it's a true representation of you or not. This is shown in the story by the way in which Norton more or less lives the reality of being an Emperor simply because the people around him play along with the conceit. They fete him as a king, give him free food and drink, and accept his fake currency as legal tender. His home town of San Francisco even touts him as a tourist attraction. Superficially, at least, he

is the Emperor of the United States by sheer force of will alone.

In addition, I think this is also Gaiman's riff on the "madness-as-sanity" trope that claims that you have to be crazy in order to stay sane in this world. At one point in the story, Dream's sister Delirium looks in on Norton and astutely sums up his eccentric behaviour by telling her brother,"

His madness keeps him sane." To which Dream cryptically responds...

The artwork by Shawn McManus is pretty nice here and well suited to the time period. Overall, I found this to be a somewhat lightweight tale, albeit one that is also rather enchanting and whimsical.

ThermidorSet during the French Revolution, "Thermidor" is a savvy look at the nature of absolute power and how it corrupts absolutely. The story's title immediately made me think of the dish Lobster Thermidor, but it actually refers a summer month in the calendar that was created during the French Revolution (Wikipedia tells me that the month of Thermidor ran from 19th July to 17th August of our modern-day Gregorian calendar).

This tale centres on Johanna Constantine, who previously appeared in volume 2,

The Doll's House, during the "Men of Good Fortune" interlude. I'm not sure if Johanna Constantine has anything to do with the character John Constantine of DC's

Swamp-Thing and

Hellblazer comics (an ancestor of his perhaps?), but I'm betting that she does. No doubt others in the forum will be able to tell me.

"Thermidor" gives us our first glimpse of Orpheus, who is the son of Dream and Calliope. If I remember my Greek mythology correctly, I believe that Orpheus' father was actually Apollo, but Gaiman says otherwise here. Anyway, Johanna is in possession of Orpheus' severed – but still very much alive – head. Within the world of

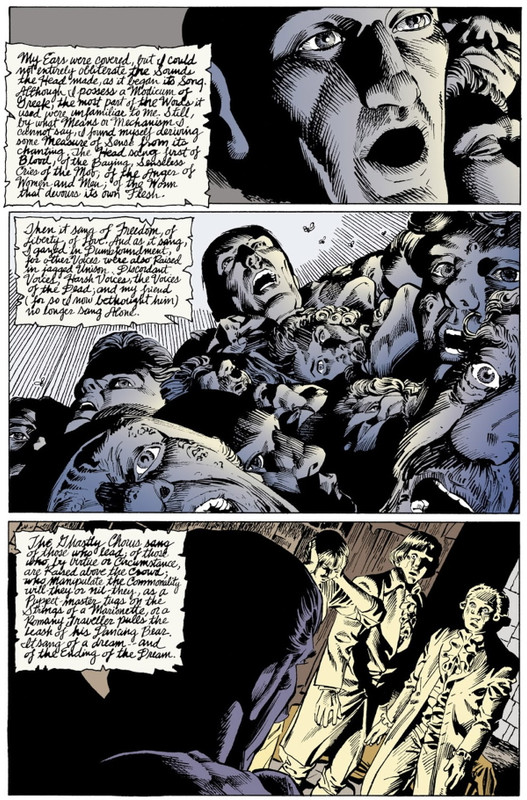

The Sandman, the head of Orpheus is a powerful supernatural artefact, which is being sought by the real life historical figure and architect of the French Revolution's "Reign of Terror", Maximilien Robespierre. Robespierre captures Johanna and forces her to reveal where she has hidden the head, which results in a scene that is both extremely creepy and very memorable, in which Orpheus' disembodied head leads a choir of other heads that have been severed by Madame Guillotine in song...

This is, of course, the fabled "song of Orpheus", which is so ghastly/beautifully that it entrances Robespierre, allowing Johanna to escape with Orpheus' head.

"Thermidor" really wasn't one of my favourite stories in

Fables & Reflections. I guess that it's important, in that it introduces Morpheus' son for the first time, and it also ties-in with the story "The Song of Orpheus", which is found later on in this volume. But I can't say that this issue really gripped me.

The HuntThis is a werewolf folk tale told by a Russian immigrant Grandfather to his disinterested Granddaughter. The scenes between Grandfather and Granddaughter are set in the then-modern era of the early 1990s, but the folk tale itself occurred decades earlier in the depths of the Russian forests.

The story follows the journey of a young male lycanthrope named Vassily, whose people live in the forest and have little contact with outside civilisation. He falls in love with the image of a duke's daughter and journeys far away from his people to find her. He hasn't gone very far when he encounters a female lycanthrope who takes him back to her forest people's encampment for rest and food. Here we get a cool cameo appearance by the witch Baba Yaga of Russian folklore, complete with her flying mortar and pestle.

Finally, upon reaching the duke's castle, Vassily manages to come face to face with his beautiful daughter (with a little help from Morpheus), but instead of wooing her, he elects to return to his people, despite the duke's daughter being everything he had dreamed of. He reunites with the young werewolf girl that he met earlier and they become lovers. "The Hunt" ends with a good twist, but I won't spoil it for you.

I have to be honest and say that I'm not entirely sure what point Gaiman is trying to make with "The Hunt". Or even if he is trying to make one! This might just be a nice story, with a good twist at the end. That said, it could maybe be seen as a parable which prompts us to consider how realistic our dreams and desires are, and whether or not they are worth pursuing. Alternatively, this could be a commentary on whether or not what we desire is always what we need. And then again, maybe this is a story about the importance of traditions and the benefits of staying with your own kind – which seems like a bit of an insular and xenophobic moral to me, to be honest.

Anyway, regardless of any underlying message, I found "The Hunt" to be a mildly diverting, but fairly lightweight tale overall.

AugustThe next story in

Fables & Reflections takes us to ancient Rome where we meet Emperor Augustus, who is Julius Caesar's nephew. For one day every year, Augustus disguises himself as a sore-riddled beggar and goes down to wander among the ordinary people of Rome and think. He does this because Morpheus once told him in a dream that, as a beggar on the streets, he would be below the gods' notice and would be able to plot and plan without them being privy to his thoughts. On this particular occasion, Augustus is accompanied by a dwarf named Lycius who sits beside him on the steps of a city temple, with their begging-bowls pushed out in front of them.

The pair talk of many things, which gives Gaiman the opportunity to explore past events in Augustus' life – in particular, a shocking revelation about the relationship between Augustus and his uncle Julius Caesar. I'm probably giving too much away if I say that this appears to be Gaiman examining the nature of homosexuality in ancient Roman society and how it differs from late 20th century social norms.

It's interesting because to the modern-day reader, this looks like a sexual assault...and, in fact, it is. But I'm not sure that it would've been viewed as such in ancient Rome. Sexuality back then wasn't divided along hetro/homo/bi-sexual lines, like ours is today: back then, sexuality was organised along the lines of whether you were someone who was being penetrated or someone who was the penetrator. It was perfectly acceptable for an adult male to penetrate a young boy (and, in fact, it carried more social kudos than penetrating a woman because women were deemed inferior). But for an adult male to penetrate another adult male was deemed to be a perversion in Roman society, much like it has been for a lot of our recent history. So, for an adult to come into the bedroom of a young boy and sodomise him – even against his will – may not have been terribly unusual behaviour in ancient Rome, though it is clearly very traumatic for Augustus.

Anyway, overall this was definitely one of the better stories in the book. I'm not sure how historically accurate Gaiman's depiction of Augustus is, or whether there's any evidence for what happens between him and Julius Caesar, but that doesn't really matter because he definitely "feels" real. That is to say that the reader "feels" as if he gets a sense of the man. I've also got no idea whether Lycius the dwarf is a real historical figure or not, but again, this is kind of beside the point because Lycius "feels" real, even if he's not.

The icing on the cake in this chapter is the excellent Bryan Talbot artwork, which really brings the bustling streets of Rome to life...

Soft Places

Soft PlacesThis story is set in the mid-13th century and follows a young Marco Polo, who, as our story opens, is lost in a desert sandstorm, having become separated from his father's caravan. The "Soft Places" of this issue's title are those places in the world where the barriers between dreams, time, and reality are at their thinnest. The desert spot where Polo now finds himself is one of these shifting places and, as a result, he is soon meeting with a stranger who knows Marco as an old man. He also meets Morpheus and the region of the Dreaming known as Fiddler's Green (in his human form). We met Fiddler's Green previously in volume 2,

The Doll's House, where he played a prominent role. Morpheus speaks of having recently escaped imprisonment, which is a reference to events in volume 1,

Preludes & Nocturnes, so clearly this is not the Morpheus of the 13th century.

Unfortunately, this story really didn't do much for me and was probably my least favourite in the book. Unlike Emperor Augustus, Polo isn't terribly well fleshed out as a character and, as a consequence, the great explorer never quite feels like a real person. To be honest, I actually found this story quite boring, which is a rarity for me with

The Sandman.

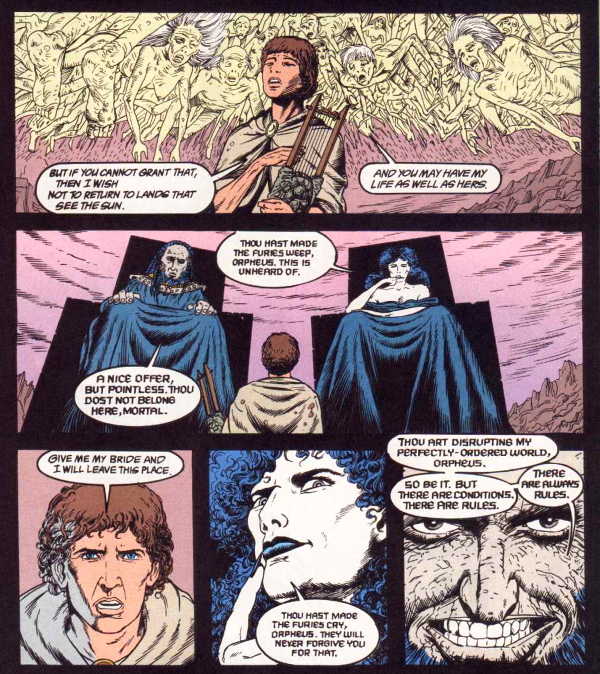

The Song of OrpheusIn this chapter, Gaiman recounts the tragic tale of the legendary musician Orpheus and his journey into the underworld in search of his dead wife Eurydice. As far as I can remember my Greek mythology, this seems to be a fairly accurate re-telling of the myth, except, as I mentioned earlier, that Orpheus is Dream's son and not Apollo's. Oh, and I should probably mention that this issue wasn't released as part of the regular series, but instead appeared in

The Sandman Special: The Song of Orpheus in 1991.

The entire Endless family are present at Orpheus and Eurydice's wedding, along with Aristaeus, the satyr-like god of shepherds and bee-keeping, who, in trying to rape Eurydice, inadvertently causes her death from a viper bite. Interestingly, we finally get to meet the Endless' missing brother Destruction at the wedding. Destruction is a burly, jovial warrior clad in armour, who seems to like a joke.

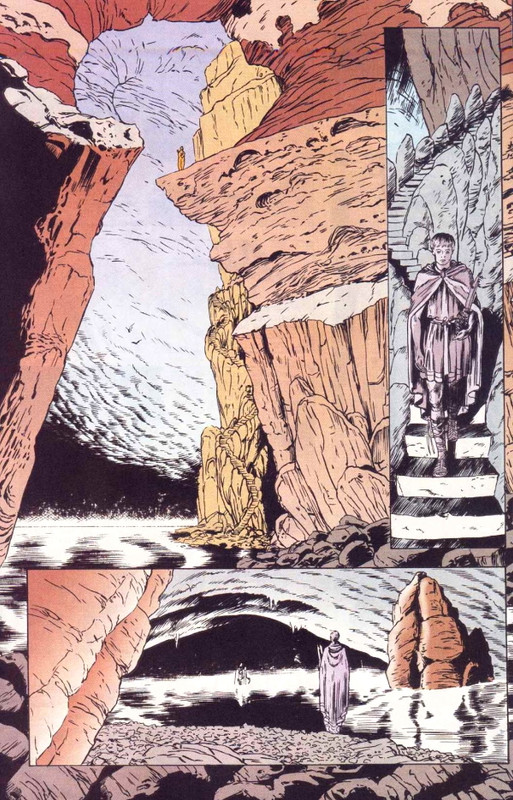

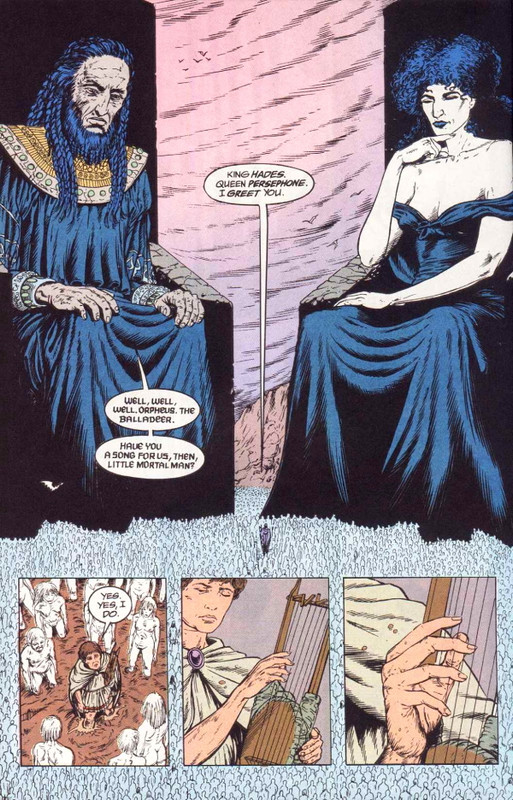

I liked this story a lot, which is in no small part due to Bryan Talbot's pencils and Mark Buckingham's inks. The art brings the wedding, the boatman on the shores of the river Styx, the assembled hordes of the underworld, King Hades and Queen Persephone, and Orpheus' death at the hands of the frenzied Bacchante vividly to life. In particular, I think Talbot really captures the oppressive grandeur of the caverns leading down to the underworld...

And his towering depictions of King Hades and Queen Persephone really took my breath away...

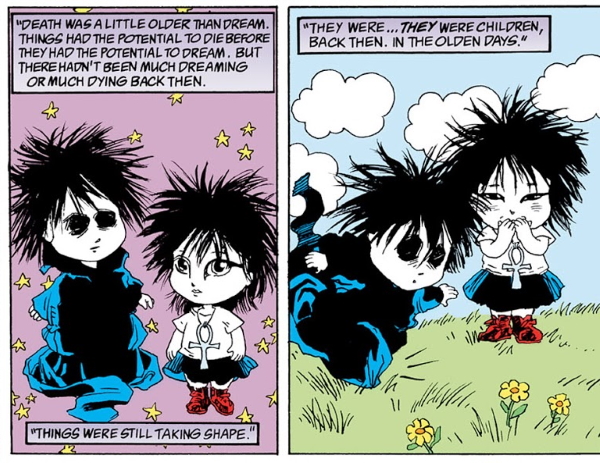

The Parliament of Rooks

The Parliament of RooksThis story is more or less just a throwaway piece, in which we follow the toddler son of Hector Hall (the '70s superhero Sandman) and his wife Lyta. Daniel, as Morpheus named the infant, has the ability to travel from our world to the Dreaming at will, having been conceived there. He is found by Eve who carries him to the House of Mystery, where Cain and Abel, the hosts of DC's old horror comic

The House of Mystery, dwell. The group all take tea together and tell stories.

Cain's story explains how a parliament of rooks works, while Abel tells a story about the Endless when they were younger, which is drawn in an almost excruciatingly cutesy way by artist Jill Thompson...

The art in this section looks decidedly manga inspired to me. I'm sure that some folks must've loved the cuteness of it all, it doesn't do much for me, I'm afraid.

The most interesting story for me was Eve's, in which she tells the tale of the first two wives of Adam, the first man. The first is named Lilith and the second is has no name. The only folkloric Lilith I know of is a sexually wanton demon from Jewish mythology, and I had certainly never heard of Adam having any wives prior to Eve. I mean, I'm fairly well read on the modern Bible, even though I'm not a Christian, but plumbing the deeper depths of Judeo-Christian theological study is not something that I've ever had the time or inclination to do. So, I've no idea if there is actually any theological basis to this, but I assume that Gaiman, who is clearly an intelligent and well read individual, has done his research.

Anyway, as I say, I found this to be a pretty lightweight issue overall. It didn't really seem to go anywhere and the continued appearances of the two hosts of DC's

The House of Mystery is perhaps my least favourite aspect of

The Sandman. Still, something that this story gives us which is pretty interesting, is a hint that Morpheus is in a relationship with someone. I assume that this isn't a reference to his old lover Nada, as her story seems to be done and finished. So, I'm thinking that this is something that will be explored in greater detail in later instalments perhaps?

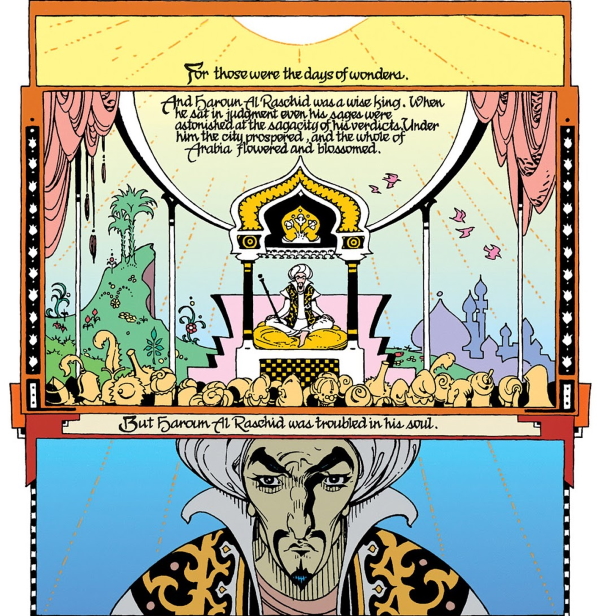

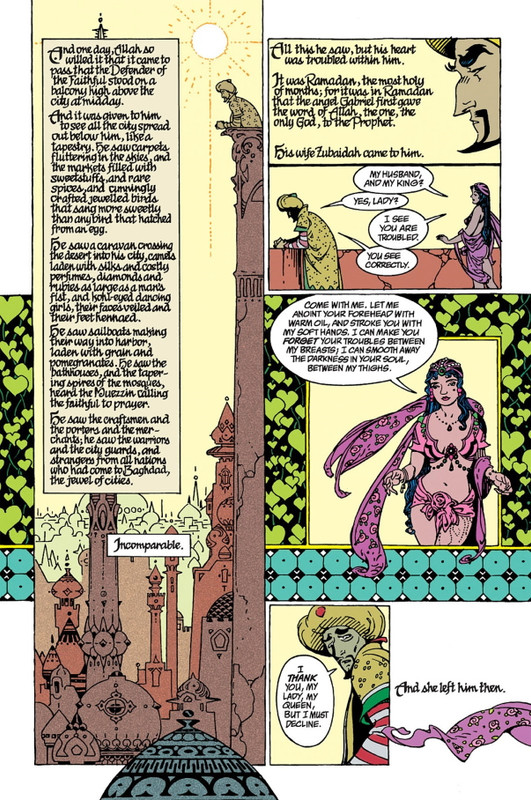

RamadanThe final story in the book is called "Ramadan", which is, of course, a month of fasting, prayer, and community gatherings in the Islamic calendar. Set in the 10th century, during the Golden Age of Islam, "Ramadan" follows Harun al-Rashid, the Caliph of Baghdad, as he takes us on a whistle-stop tour of the city. Al-Rashid, who was a real person, tours the spectacular architecture of Baghdad, with its bejewelled mosques and minarets, takes in the centres of high art and advanced learning, visits the teeming marketplaces, with their exquisite foods and flying carpets, and also shows us the earthly pleasures that the city has to offer. This then, is a glimpse of Baghdad at its moment of cultural apex; the greatest city that Allah ever created in the greatest age of mankind.

Unfortunately, despite all his wealth and power, al-Rashid is troubled by the thought that his perfect kingdom cannot last forever and will one day be no more. In desperation, he summons Morpheus, the Lord of Dream, and asks him if he will buy the city from him so that it may live forever in the dreams of men. Dream agrees and, as the bargain is completed, flying carpets fall from the sky, the perfect buildings of the city suddenly look much more decrepit, and the marketplaces become places full of the wretched poor. On the final page, we flash forward to the Baghdad of the early 1990s, which is a war-torn, bombed out shell of a city.

The first thing to note about "Ramadan", aside from it clearly being influenced by the

Arabian Nights, is that it is beautifully drawn by P. Craig Russell. This may well be the artistic highlight for the series so far. Russell's drawings of Baghdad's gleaming cityscapes – all multicoloured towers, mosques, and minarets – and exotic palaces have a slightly European,

bandes dessinée flavour to them to my eyes. But the art and colouring job still manage to sucessfully conjure up the arabesque majesty found in Islamic art perfectly. It really is a breathtakingly beautiful comic...

This has got to be one of the best stand-alone stories in the series so far, comparable to the excellent "The Sound of Her Wings", "Calliope", and "A Midsummer Night's Dream", even if it never quite reaches the heights of those three earlier stories IMHO.

In the story, Gaiman takes us from Baghdad's heyday to its then-present state, having been reduced to bombed out rubble by the first Gulf War. The ending is quite powerful, for sure, but more interesting to me was the immediate change in the city as soon as Morpheus accepts al-Rashid's deal. Once the deal is sealed, the marvellous architecture of Baghdad vanishes, the fantastic colours of the buildings become muted browns, and the magic flying carpets fall limply to the floor. I took this to be evidence that this "Golden Age of Baghdad" was never anything more than a dream. As a seat of learning and art, the city was amazing by the standards of its time, yes, but it wasn't ever quite the fairytale, Arabian Nights-esque place we imagine it to be. Thus, Gaiman deftly navigates his way around any accusations of Islamophilia.

For me, "Ramadan" is a story about the power of dreams, imagination, and storytelling as a way of preserving humanity's greatest wonders.

Summing up, I don't think this was one of the better volumes of

The Sandman. It has its moments, for sure, and a handful of these tales are really very good. But I found others to be much less satisfying. There's frequently a fairly overt narrating voice found in these stories, which I'd not noticed before in

The Sandman, and the collection features so many different art styles and subject matters that it has a haphazard, scattershot feel. It should also be noted that these stories don't really seem to add much to the over-arching narrative of the series, although it may turn out that Gaiman is planting seeds here for future instalments.

Ultimately, this was a solid, but not amazing volume. I think it also suffers by coming on the heels of

Season of Mists and

A Game of You, which were both truly excellent. This might be the first volume of

The Sandman that I've read which I would consider calling "inessential."