|

|

Post by MWGallaher on Nov 16, 2020 7:34:27 GMT -5

I wonder if Marvel had any trepidation (or blowback) from using the name Night Rider for its eerie, white-garbed, hooded vigilante, as the KKK (and other white supremacist, vigilante groups as well) were often referred to as night riders and their violent attacks as night rides. I hadn't thought of that, but I would conclude so, because they eventually change the name once again to "Phantom Rider"! |

|

|

|

Post by tarkintino on Nov 16, 2020 8:49:41 GMT -5

Then we can look forward to a time displaced Kid Colt, paired with Knight Rider.... Noooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo!

..and no!  |

|

|

|

Post by MDG on Nov 16, 2020 9:37:47 GMT -5

I wonder if Marvel had any trepidation (or blowback) from using the name Night Rider for its eerie, white-garbed, hooded vigilante, as the KKK (and other white supremacist, vigilante groups as well) were often referred to as night riders and their violent attacks as night rides. I'm more curious if they had trepidation about using the name "Linda" to credit that Two-Gun Kid story, so went with "L.A." |

|

|

|

Post by profh0011 on Nov 16, 2020 14:56:01 GMT -5

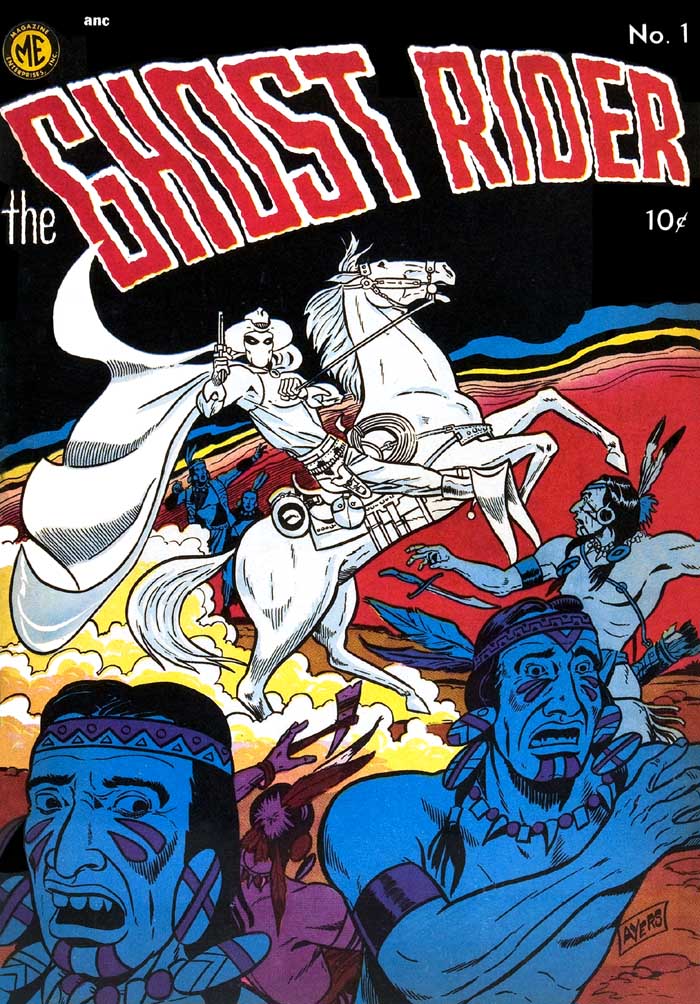

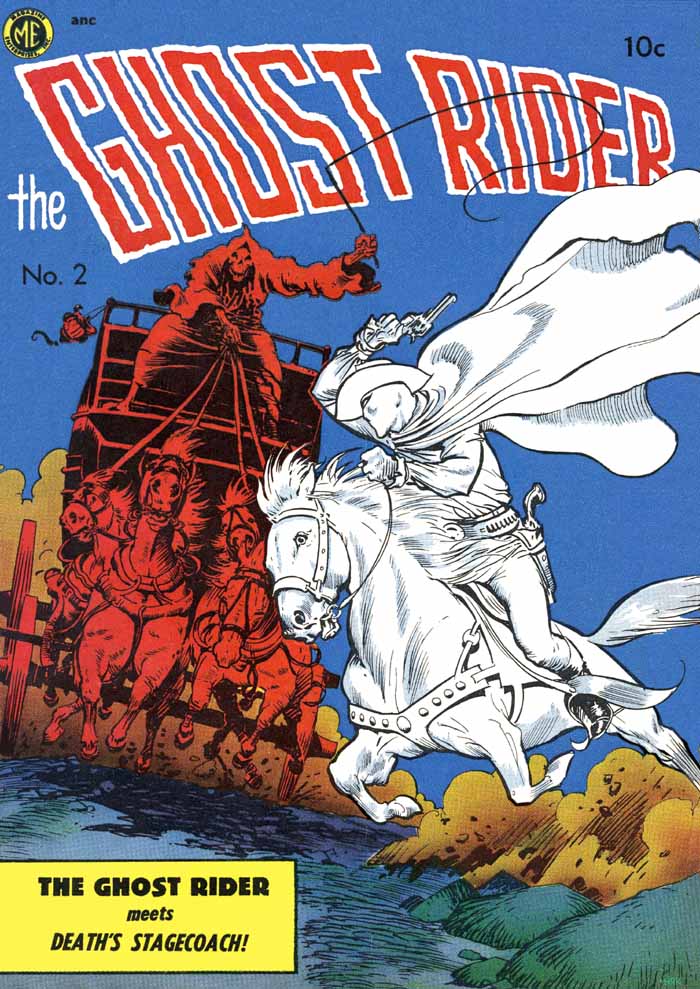

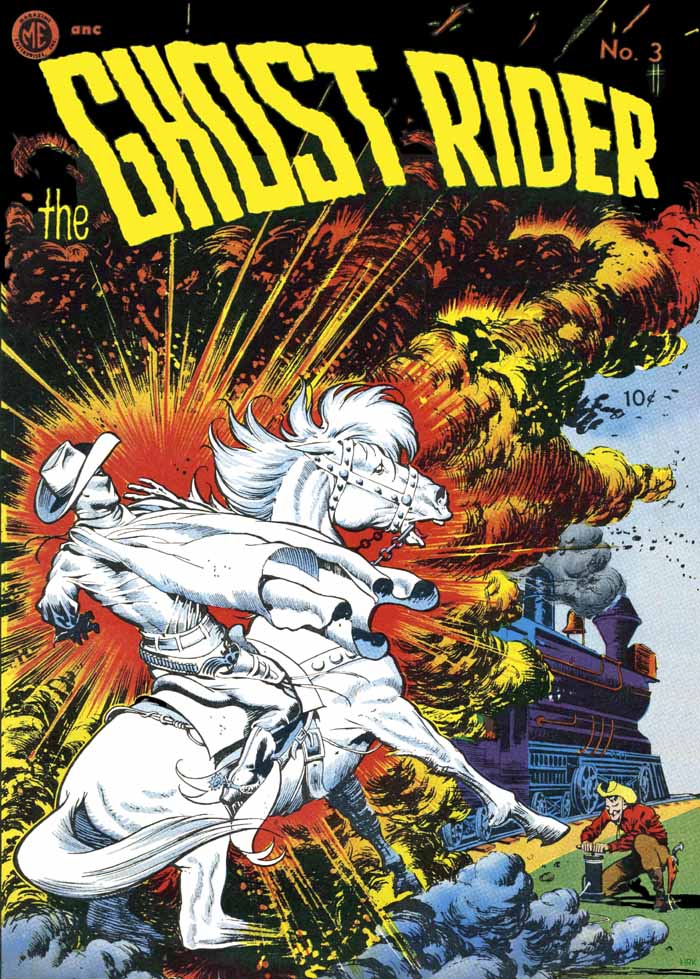

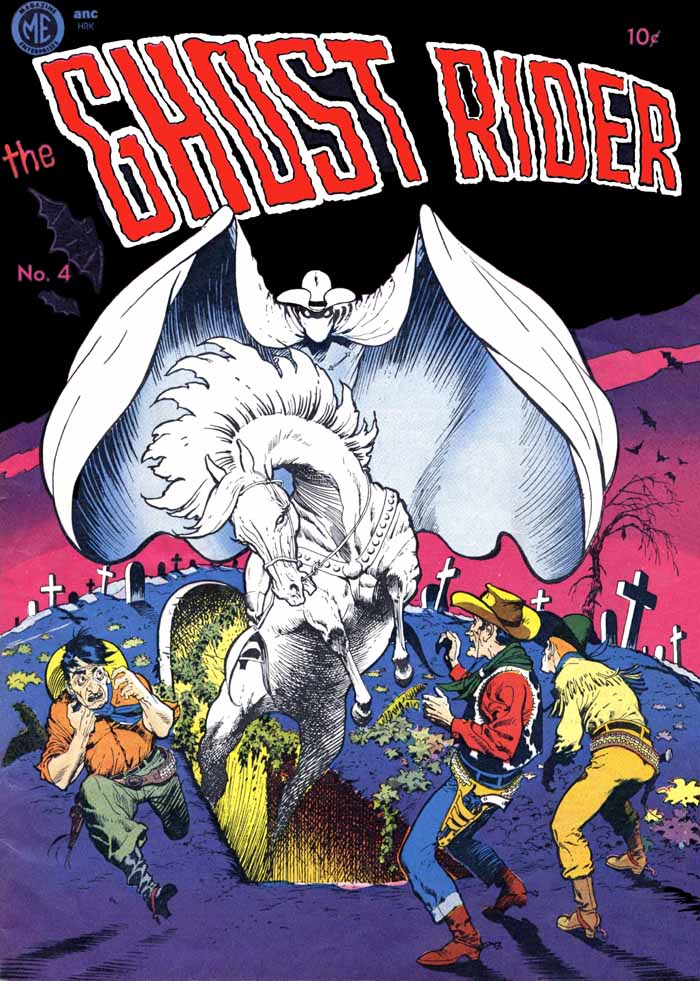

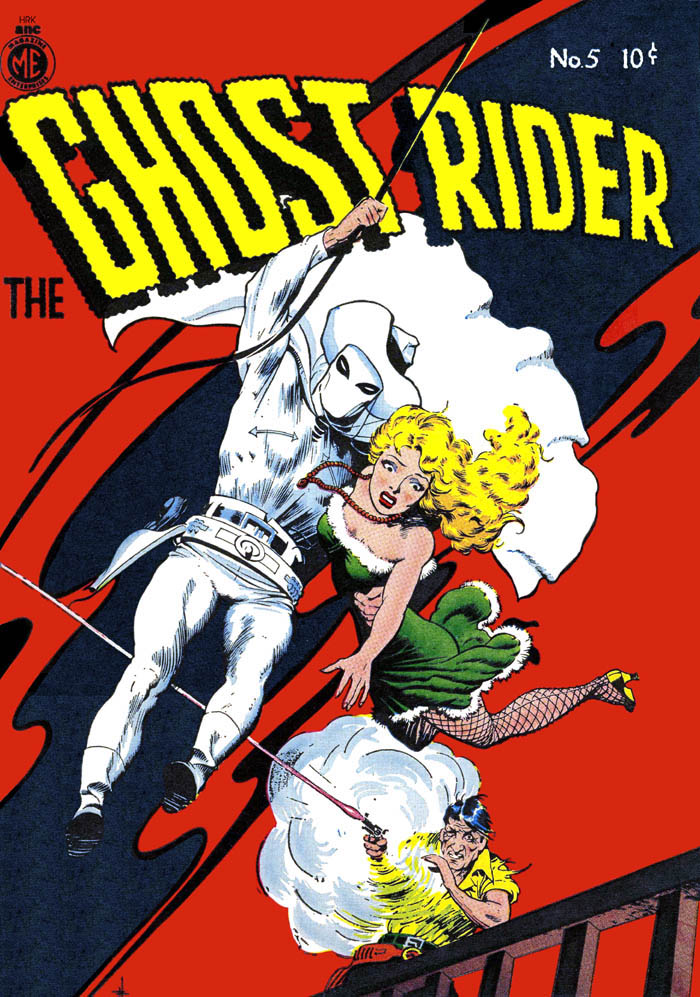

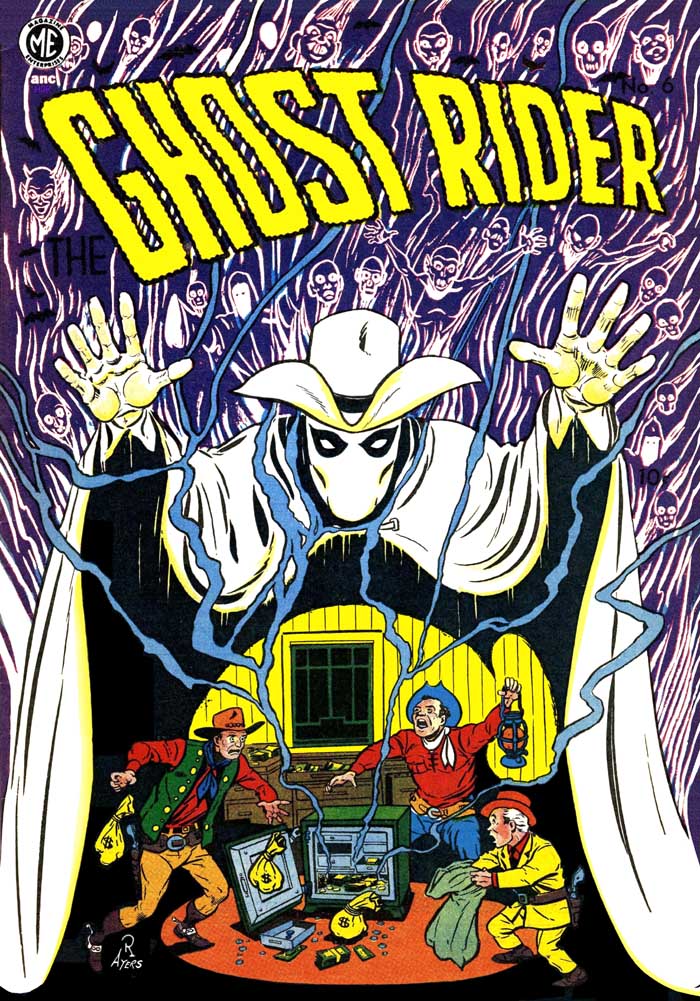

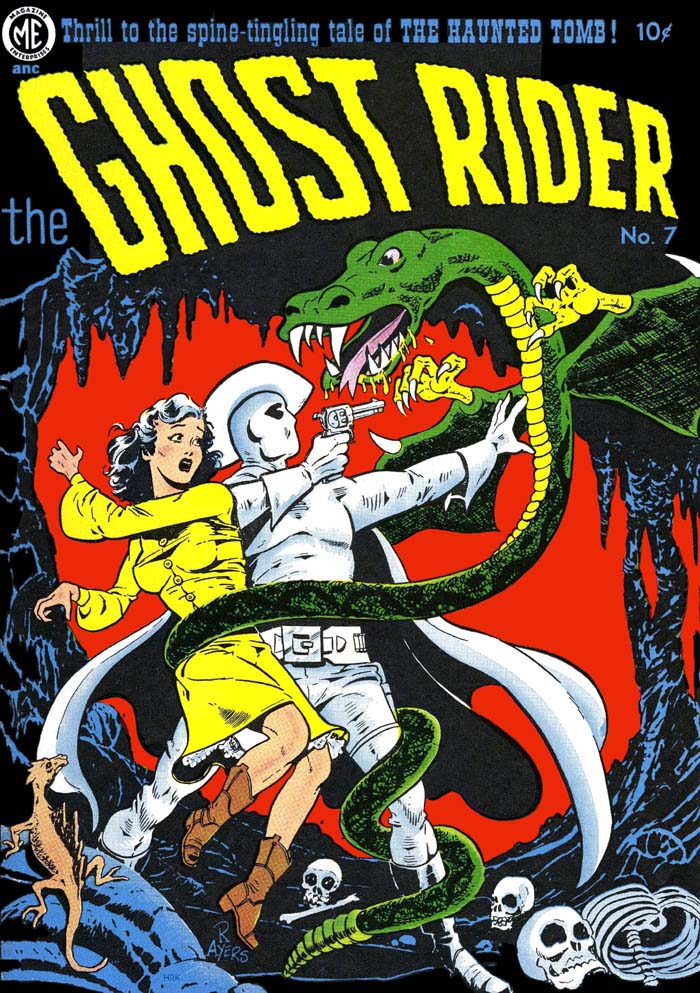

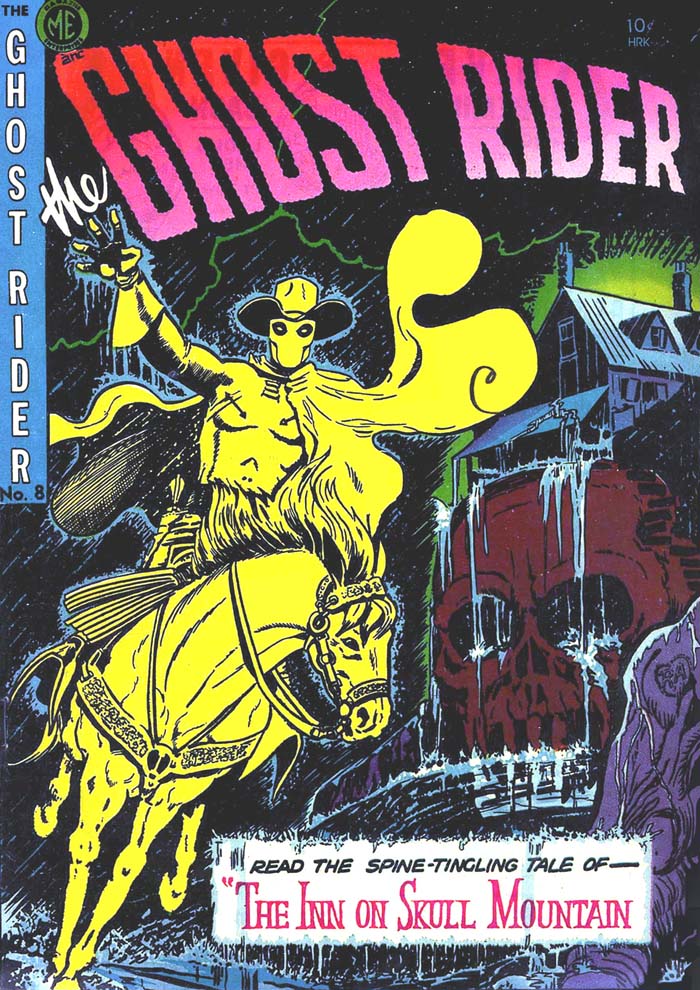

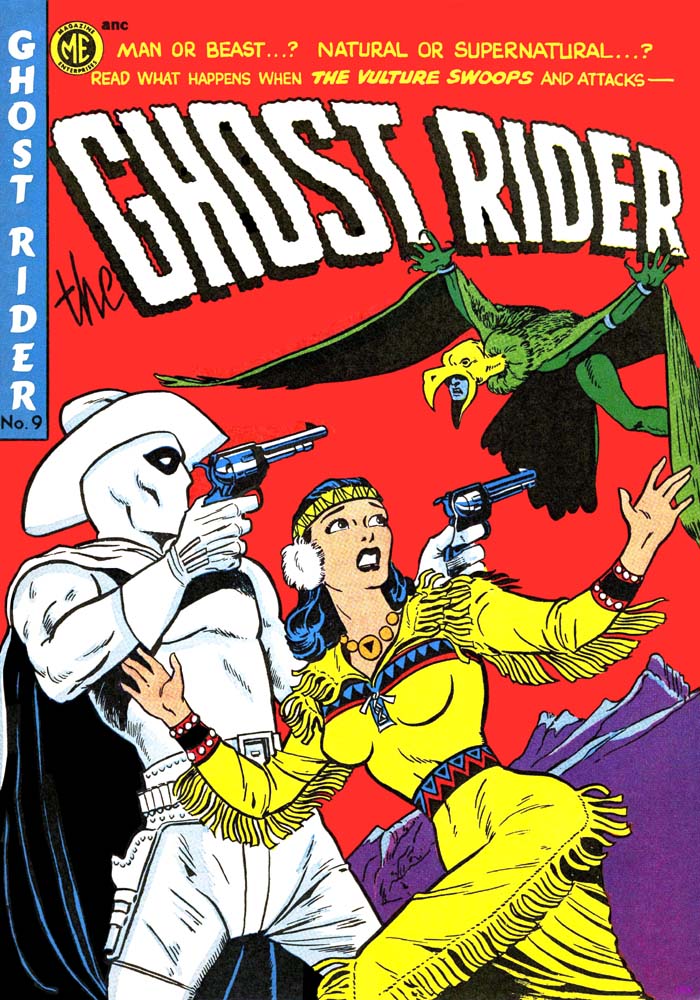

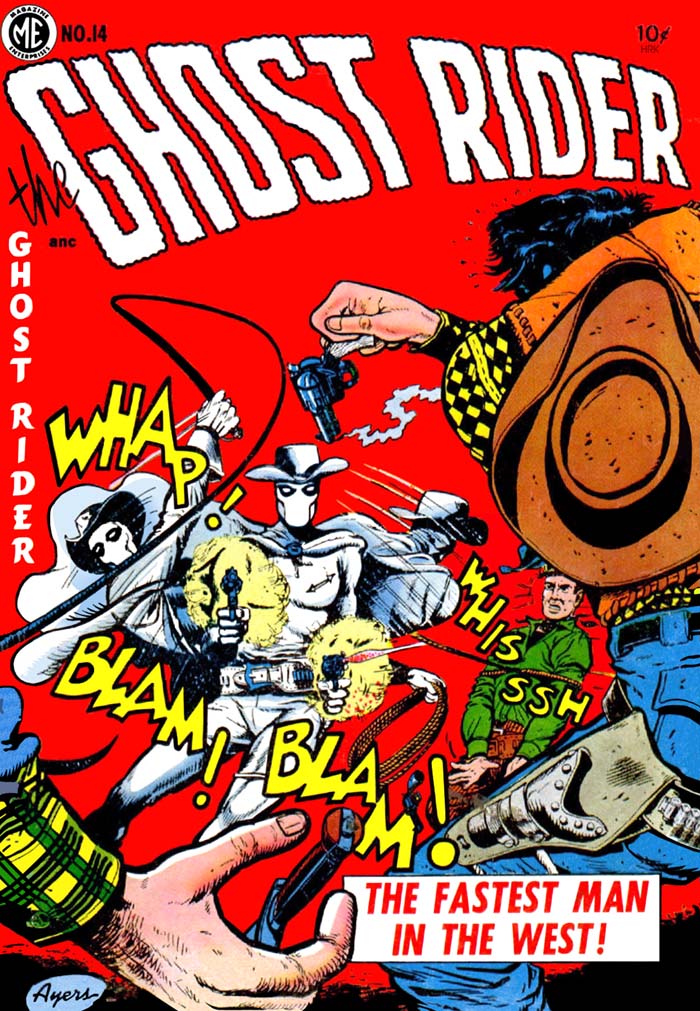

I've seen at least 4 instances where a "new" Marvel character was PUBLISHER-mandated (as if "editor" madates were soul-less enough). In each case, Martin Goodman ordered new characters so he could re-use ("STEAL!") names previously used by defunct publishers. In each case, some of the earliest stories with these "new" characters were among the worst-conceived, worst-written in all of 60s Marvel... Daredevil (Lev Gleason) Ghost Rider (Magazine Enterprises) Captain Mar-Vell (Fawcett) Ka-Zar (in this case, Marvel was rippng off themselves) Magazine Enterprises publisher Vincent Sullivan threatened to sue Goodman over the new western "Ghost Rider", and what I noticed was, the magazine was cancelled ONE month after it went monthly! So it wasn't lack of sales that put it down. However-- one month AFTER that... the new "Captain Marvel" debuted. Goodman just couldn't be stopped. Marvel's western "Ghost Rider" (note quotation marks) was mostly a concoction of editor Roy Thomas. I can tell this by how he named the guy "Carter Slade" (gee, shades of Roy's favorite DC hero, Carter Hall), made him a SCHOOL-TEACHER (gee, as Roy had been before becoming a comics professional), and how you had a character who should have known better insisting that the masked hero was secretly a bad guy (gee-- SHADES OF FREAKIN' SPIDER-MAN), not to mention including a kid sidekick (something Marvel's editor would not have approved of), and a REALLY LAME soap-opera involving a woman who was already engaged who kept shoving herself in Carter's path, but then repeatedly pointing out that she wasn't available (so get the HELL out of his way, you stupid cow!). Basically, that cast was one of the most unlikable and infuriating of all of 60s Marvel. On top of this, the dialogue by Gary Friedrich-- and sometimes Roy himself (filling in uncredited-- BUT I COULD TELL, there was no mistaking his intensely-annoying style) made the book just about unreadable. So, recruiting the artist of the ORIGINAL character to WRITE THE STORIES and DRAW THE ART-- Dick Ayers-- didn't help much, because by the time Ayers was brought on board, Thomas had already destroyed any hope the series might have had. Carter Slade was brought back in WESTERN GUNFIGHTERS so they could continue publishing leftover stories and new ones, while avoiding putting out a BOOK whose name AND character would be an obvious Copyright violation... and before long, Carter was KILLED OFF (a typical Thomas move) and replaced with a brother who was an actual... U.S. Marshal. Oy. Goodman STILL wanted to reuse the name "Ghost Rider", which is why Gary Friedrich, whose big thing was motorcycles, eventually created JOHNNY BLAZE. I just wish that had been the name of the series.

I like to tell people... Carter Slade was NOT "the original Ghost Rider"... U.S. Marshal Rex Fury. Marvel NEVER published the original GHOST RIDER. Magazine Enterprises did. And, later, Bill Black's Paragon Publications and AC Comics. However, at some point, Marvel's lawyers sent Bill Black a "cease and decist" order... to which he responded by thumbing his nose at their B***S***... and changing the name to... HAUNTED HORSEMAN.

GHOST RIDER was not supposed to be a western version of Spider-Man... he was a "spooky" version of THE LONE RANGER. (And he had a Chinese sidekick!)

|

|

|

|

Post by brutalis on Nov 16, 2020 21:05:57 GMT -5

I always knew of the original Ayers Ghost Rider, seeing many pictures of the covers and wondered how they might be. Over the last 2-3 years I have grabbed affordable copies of Bill Black's Best of the West so I can honestly say they were wild, wonky and weird in the best possible ways. Marvel never really made much of an effort to make anything special of the character, yet as a youth I was captivated with him under any name change they gave him. No matter how poor the stories were I would buy anything featuring him in doing my part to support more stories.

So much wasted potential😢

|

|

|

|

Post by tartanphantom on Nov 16, 2020 23:44:35 GMT -5

While I don't have any issues of the actual ME Ghost Rider series, I do have a couple of issues of Tim Holt Western (also published by ME) with Ghost Rider stories-- after all, that's where he got his start before getting his own book. Don't have Tim Holt #11 though-- that's the Ghost Rider 1st appearance, and it's a wee bit beyond my pocketbook.

|

|

|

|

Post by profh0011 on Nov 17, 2020 11:23:58 GMT -5

The TIM HOLT comic was really Ghost Rider's regular monthly "home"-- just as DETECTIVE COMICS was for Batman, ACTION COMICS was for Superman, and SENSATION COMICS was for Wonder Woman. ME's GHOST RIDER (which ran 14 issues) was a quarterly, which more than doubled the amount of GR stories each year. All 14 issues were also part of ME's " A-1" anthology, meaning every issue had 2 different names & numberings. That can get confusing! At the GCD, each issue is therefore listed twice. I ran across a similar (but even more confusing) situation with a Brazillian horror anthology in the 60s, but the Guia Dos Quadrinhos database site down there is not set up to allow any book to be posted twice, which has made it frustrating for me, as the one guy who runs the site didn't believe me when I told him I'd figured out the bizarre double-numbering of so many issues. The Comic Book Plus site has every issue of Magazine Enterprises posted online to read for free! I also put a lot of effort into cleaning up scans of the covers. (I had a problem with my computer monitor getting darker as it went, and I was over-compensating before I realized what was going on. So a lot of the scans from that period of clean-ups look a bit odd... oh well. I'm too busy to go back and make further adjustments.) professorhswaybackmachine.blogspot.com/2012/05/tim-holt.htmlRex Fury debuted in TIM HOLT #6 (May 1949). For 5 episodes, he went under the name of " The Calico Kid". The 1st episode had art by Ernie Bache. The 3rd was by Fred Guardineer. The 2nd, 4th & 5th were by Dick Ayers. The 6th episode was the "origin" of the GHOST RIDER. From that point on, every single episode was illustrated by Dick Ayers. Many of them were inked by Ernie Bache. It kinda reminds me a bit of the John Buscema-Ernie Chan team. I've always liked Ayers' pencils more than his inks. He often said he hated inking anyone else, to him it was just a job. Myself, the only penciller I liked seeing him teamed with was Jack Kirby. The rest of the time, it seemed he was wasting his best talent. Crazy enough, when the Comics Code came in, GHOST RIDER was one of the casualties, since the series had delved more and more into horror-- at first, fake horror, but more as it went, real supernatural horror. Marvel's rip-off version never did that-- one more knock against it. JOHNNY BLAZE went the other way, with SATAN as the main recurring villain early-on. Annoyingly, later on, Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter ordered the removal of any references to Satan or Jesus from the series, and by the time Roger Stern came on briefly, he did a retold version of Johnny's origin revealing it was the Mephisto character, not actually "Satan". That just watered it down in my eyes. |

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on Nov 17, 2020 19:55:29 GMT -5

Giant-Size Kid Colt #3, July, 1975 “Death Duel with Dack Derringer”, 20 pgs Written by Gary Friedrich Drawn by Dick Ayers Inked by Vince Colletta Lettered by Jean Hipp Colored by Petra Goldberg Edited by Len Wein  Cover by Gil Kane Summary: We open with a shocking scene: gambler Dack Derringer shoots Kid Colt point blank in a dispute over a game of poker. Seem’s Dack’s holding four aces, but Colt had just discarded an ace to build his full house! Dack backs away to the swinging saloon doors, holding his pistol on the onlookers who’ve objected to the “cold-blooded murder” they just witnessed, but Dack collides with school teacher Carter Slade, arriving on the other side of the doors, curious about the shot he heard. Both are knocked down, but Dack rides off, while Carter sees to Kid Colt, who’s not dead, after all, just gravely wounded. Since Doc Bentley’s out of town, Carter takes Colt home for recovery, and assigns the townsmen to round up a posse, since the sheriff’s out of town, too. Seems Carter’s pretty good at doctoring, given that the bullet passed close to the Kid’s heart. He sends his young houseboy Jamie to fetch old Mrs. Benson to serve as Colt’s nurse, because as soon as the sun sets, Carter Slade’s gonna do some Night Riding! Darkness falls, and we get a gander at the Night Rider’s set-up: a secret cave where he keeps his glow-in-the-dark Night Rider gear, complete with projection lantern and luminous rope. Still in his civilian garb, Slade hits the trail of Dack Derringer.  But by the time he catches up with the posse, he’s in the striking solid white costume of “He Who Rides the Night-Winds”, adopting an imperious, dramatic speech pattern as he scolds the posse who are abandoning the pursuit. He pulls his disappearing act, vowing that Dack Derringer will soon be imprisoned…or dead! Back at Carter’s homestead, Kid Colt is recovering remarkably. Three days later, in another town miles away, Dack Derringer finds that his bad reputation precedes him, thanks to the Night Rider who has beaten him there. If Dack’s money isn’t good enough in this town to buy him a beer, he thinks his bullets will be good enough to take down a Night Rider. To his shock, Dack’s bullets do no harm to the spectral cowboy taunting him from across the street, a spectral cowboy who vanishes before the astonished eyes of all observers. (Readers in 1975 know that Dack was shooting at an image projected from the Night Rider’s lantern!) Dack flees in terror, but runs immediately into a more physically substantial Night Rider, who unseats Dack from his saddle with a lasso, forcing him to attempt an escape on foot. With no option but to resort to gunfire, Dack finds that this time, his shots do some damage (if only a flesh wound that sends him tumbling unconscious to the dirt)—the Night Rider is human after all! He steals the Night Rider’s horse (discovering that the apparently solid white steed is a common chestnut brown beneath the luminous phosphorus dust the Night Rider covers his horse in). That horse is way beyond anything the townsmen’s mounts are capable of matching. Dack is gone with the wind, and the wounded Night Rider makes plans to head home, hoping Kid Colt is recovered enough to assist him. Colt is indeed on the mend, and ready to leave the company of Jamie and Mrs. Benson to pursue the “two-bit card chisler” (sic) that shot him. Night Rider, on a borrowed “worthless nag”, has managed to catch up with the posse, who have Dack Derringer boxed in against the walls of a closed-off canyon. Night Rider worries that if the posse catches Dack, they’ll discover that his horse was covered in phosphorus, spoiling the myth he’s built up around himself. He ponders aloud whether it’s worth letting Dack go free so that he can’t reveal what he’s learned, but Kid Colt, who’s also arrived on the scene in time to overhear, and to talk some sense into the ghostly gunslinger:  And finally it’s a Western Team-Up! Derringer has discovered that this apparent trap provides him a position from which he can simply slaughter the posse from on high. The posse members give it a go, but back down for fear of losing one of their own. If only they could get a couple of men behind him… Kid Colt’s a little leery of teaming with a spook, but Carter convinces him: “As with all things spiritual—you can only trust me! And trust me you should! After all, if I wanted to kill you, I could have easily done so long before now!” One of the posse’s gotten tired of waiting Dack out, and makes a brave move, but it’s one that earns him a bullet in the chest. That’s enough to get this team-up into action, right? Well, after a bit more jaw-boning, maybe…   Night Rider attempts to spook Dack Derringer, but Dack’s no dummy, and takes aim at the haunted horseman he knows to be human. Oops! He fell for the projection again, operated from the rocks above by Kid Colt! Faced with a Night Rider every way he turns, Dack loses his composure and doubts his convictions—maybe the Night Rider’s a genuine spook after all? Dack bows to the mystery man in a plea of repentance, and the Night Rider… prays?!

Before Dack can shoot the sermonizing spectre, Kid Colt takes him out with a shot from behind. Unnecessarily, according to the Night Rider, who had a back-up plan ready. He explains that his prayer was just an attempt to determine whether Dack’s remorse was sincere, and, alas, it was not. With the story coming to a close, Night Rider feels obliged to attempt to arrest the fugitive Kid Colt, but allows him to depart with his claims of innocence. Warning the Kid to clear his name before venturing again into Night Rider territory, Colt departs with a claim to have seen through the Night Rider’s act all along. Comments: With a more generous page count, this is the most engaging of the team-ups we’ve looked at so far. First off, the lowered stakes provide an interesting contrast to the usual fare. This is no old-west supervillain with a fancy costume and nickname (which were standard threats in Marvel’s Ghost Rider series) or a gang of thugs threatening the safety of the town or rustling cattle from an innocent ranch-owner like we might see in a Kid Colt story. It’s just some guy, who’s shot another guy and gone on the lam. For a series named after “Kid Colt”, the Kid himself does next to nothing in this story. He gets shot, he talks the Night Rider into doing the right thing, serves as the Night Rider’s technical assistant, and shoots his earlier assailant in the back, unnecessarily. It’s not much of a team-up; it’s a Night Rider story, with Kid Colt guest-starring, and no denying it. And the original crew of Marvel’s Ghost Rider, Friedrich and Ayers, were probably as happy focusing on their old friend as the readers who were more interested in superhero-style costumes and gimmicks than in typical western comics. Which, by 1975, were quite likely in the majority. I’ve gotta admit, the prayer scene really threw me for a loop. Seeing the hero pause the action for a full page of prayer to the almighty was a surprise, and had me wondering whether Night Rider was supposed to be some kind of religious crusader. Revealing that it was a ruse was kind of a let-down, but there’s still the hint that Night Rider was more sincere than he was letting on in hoping that Derringer had genuinely had a change of heart. I also liked the bit where Dack was disappointed to discover that he wasn't welcome to do any gambling thanks to Night Rider spreading the word about his bad nature. Taken together, it does make the Night Rider out to be someone intent on taking his enemy down psychologically in order to get him to redeem himself under pressure. Not the most genuine of redemptions, no, but it's different enough to be notable. I do mightily appreciate Professor H’s giving us all the low-down on the original Ghost Rider. While I have more appreciation than he does for Marvel’s version (but I loved your takedown of it, profh0011 !), it has always rubbed me the wrong way that Marvel was so blatant about co-opting the defunct character without permission from Magazine Enterprises, without making the kinds of changes they did to distinguish Daredevil and Captain Marvel from their predecessors. But that all-white costume is irresistibly compelling. It surprises me that few publishers opted for that, as effective as it is. (I can recall Marvel’s own White Tiger, but that’s about it.) While I'm not a big fan of Dick Ayers' work, I do have some nostalgic attraction to it, and I've gotta say he does some good "supporting actors". In this one, Dack Derringer is the stereotypical weasel with a slick look and a thin mustache, cliche but effective. I didn't have any trouble with Colletta's inks, entirely adequate for the job. Also of interest, among the reprints backing up the lead story is "Fury of Farrow Gap", as mentioned before, the most recent solo Kid Colt story prior to the previous issue's solo. Werner Roth does a pretty fine job, aided ably by Colletta, and we also get some reprints featuring the artwork of long-time Kid Colt artist Jack Keller, perhaps better known for the racing stories he did for years at Charlton. I'm quite fond of Keller's work. It's pleasant and has a lot of character, but still looked a little old-fashioned and simplistic in the 70's. And with that, Giant-Size Kid Colt came to an unsurprising end. It had played its part in the Marvel Western Team-Up micro-genre, picking up the banner from its cancelled precursor, using its inventoried material, and following the same trail while providing all-new content to accompany the then-running Night Rider reprint series.

|

|

|

|

Post by profh0011 on Nov 17, 2020 22:20:31 GMT -5

Credits in 60s Marvels were often inconsistent, leading some Marvel fanatics to insist that what was listed was "correct", even when it wasn't. For example, the 3 issues of DAREDEVIL where Bob Powell worked with Wally Wood had the credits written 3 different ways, suggesting the issues were done differently, when they weren't. All 3 had Wood on story, layouts & inks, Powell on pencils. #9 & 11 had dialogue by the editor, #10 Wood dialogued his own story. But editorial comments suggested #10 was the "only" one Wood wrote, which was total B***S***. Editorial comments were also rude, insulting and derogatory toward Wood and his abilities-- it's NO DAMN WONDER he took up the opportunity to jump Tower Comics right after and spearhead their "THUNDER AGENTS" line. As he put it, "The page rate was the same, but at least at Tower I GOT PAID for the writing I was already doing."

Likewise, the 1967 "Ghost Rider" splash pages, some clearly credit Dick Ayers with the story plot, and Gary Friedrich on all of them, when in fact, Ayers wrote ALL of the stories, and Friedrich only did dialogue on certain episodes, with Roy Thomas filling in uncredited on a few.

This may-- or may not-- have changed later on. Crazy but true: Dick Ayers much later did a number of "Phantom Rider" episodes as back-ups in the 90s "Ghost Rider" revival-- the ones without Johnny Blaze. However, he ALSO did a few brand-new "Haunted Horseman" stories with Rex Fury, written & inked by Bill Black, for AC Comics.

|

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on Nov 18, 2020 6:55:30 GMT -5

Thanks for noting the issue with credits, Prof. I very much appreciate that the role the artists actually played in writing the stories in those 60's Marvels is becoming more widely acknowledged. In those Daredevil and Ghost Rider issues, especially, you can sense "the editor" regretting his allowing readers to get a somewhat more accurate picture of the "writing" process and re-burying it with credits that, sometimes rather creatively, obscure the division of labor: in issue 3 of Ghost Rider, it's "written by Gary Friedrich" and "plotted and drawn by Dick Ayers", and in issue 4, it's "Gary Friedrich * Dick Ayers Scrutiny of Sepulchral Seances!" What the heck?! In issue 5, the credits are in the style of newspaper article with headlines "Gary Friedrich's seething scripting showcased!" and "Dick Ayers' artwork called awe-inspiring"...and even "Stan Lee Edits and Embellishes Another Frontier Fantasy!" (Wait, isn't "embellishing" usually a synonym for "inking" in this context? Talk about misleading credits! I assume Stan's saying he rewrote some dialogue.) Issue 6 is just a "Gary Friedrich and Dick Ayers Monument of Mysterious Mysticism" while issue 7 winds us all the way to the standard "Written by: Gary Friedrich Drawn by: Dick Ayers".

I'd missed out on Ayers' 90's Phantom Rider backups in the series reprinting the "Original Ghost Rider". It looks like there were quite a few of them, running from issues 3-20, culminating in a Western Team-Up between the Rider and El Aguila, a Mexican western adventurer! I think I might have to get around to that one here, somewhere down the line!

|

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on Nov 18, 2020 8:57:32 GMT -5

I should have drawn some attention to the fact that the Night Rider in the afore-mentioned Giant-Size Kid Colt #3 was Carter Slade, Marvel's first incarnation of the then-Ghost Rider. In "real-time" continuity, Carter Slade had died and been replaced by his brother Lincoln, as Henry mentioned in an earlier post. But it was Carter who was appearing in the reprint comic at the time, which had not yet (and never would) catch up to the Lincoln Slade era of Marvel's Western Gunfighters comic, so it made sense to align this story with the Night Rider material being published contemporaneously in 1975. Of course, in stories set in the past, especially when not-dependent on issue-to-issue continuity, there was no need to explain that this story occurred prior to Carter Slade's death (or, for that matter, young Jamie's death--according to Western Gunfighters, Jamie had an ill-fated turn as Carter's first successor).

Western Gunfighters is another series I'll be getting around to, as I've learned that it, too, featured a team-up appropriate for attention here.

|

|

|

|

Post by profh0011 on Nov 18, 2020 13:33:14 GMT -5

Most of those I never read, except where I found scans of the original art online. No, really! I've also read about a lot of this stuff, while doing research here and there. I forgot that just within the context of the marvel western GR series, they had 3 different people taking on the name. To me, Marvel just totally disrespected the memory and legacy of someone else's character. I did read when Steve Englehart (no longer on top of his game) did an excessively-long time-travel story in WEST COAST AVENGERS, in which he did even worse things with Phantom Rider (or whatever he was being called at that point). They really made it difficult to follow a lot of these obscure series in the 70s, often jumping from one book to another to another between appearances. I was thinking about this just yesterday with their ESSENTIAL MARVEL HORROR reprint collections, which really made it much easier to read some of those characters who kept jumping books between almsot every story. The Night Rider also appeared in GHOST RIDER #50 (Nov'80) where he teamed up with Johnny Blaze, in a story by Michael Fleisher and Don Perlin.

I may be missing some of these, but Rex Fury appeared in GREAT AMERICAN WESTERN presents SUNSET CARSON #5 (?? / AC / 1991). " Ghost Town Gauntlet" (10 pages). Story & inks by Bill Black, pencils by DICK AYERS. Sunset Carson teams up with Haunted Horseman.  As far as I know, the last appearance of Rex Fury was in BEST OF THE WEST #31 (AC / 2002). " The Curse Of The Carpathians" (5 pages) Story by Bill Black, full art by DICK AYERS. (I would have preferred if Black had done the inks, but that's me.) Now that I think about it, I really don't know if Ayers wrote the story himself, and Black only did the dialogue. The thing is, unlike Marvel's editor, I'm pretty sure Bill Black did it all, depending on the story.  This one's IN STOCK at AC Comics! link |

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on Nov 19, 2020 15:53:11 GMT -5

Kid Colt Outlaw #201, December 1975 Written by Gary Friedrich Penciled and inked by Dick Ayers Artie Simek, letterer Vic Mortellaro, colorist edited by Marv Wolfman  Cover by Gil Kane “Death in the Devil’s Dungeon” Summary: The story opens with its three main characters about to cross paths: the Kids are about to happen upon (from different directions) a stagecoach containing Burt Riker (“gambler—con man—fast gun”).  Also arriving, a gang of bandits intent on holding up the stage for its safe box. While Rawhide and Colt start firing on the bandits, Riker tries to make out like a bandit with the beautiful young lady sharing the passenger’s seats. The bandits flee at the Kids’ “two-man army”, and the Kids attempt to vamoose when a posse arrives in pursuit of the robbers, lest their undeserved outlaw reputations get them in trouble. They’re unable to escape, and are taken into custody by the sheriff. Still in the coach, Riker continues to make unwelcome advances as the situation outside is resolved, telling the woman “it’s hard to tell the good guys from the bad guys!” One of the captured, masked bandits accuses Colt and Rawhide of being the ringleaders, and Riker, finally exiting the coach with what appear to be lipstick marks on his face, vouches not for the Kids, but for the bandit, claiming that he himself was recruited to ride as a passenger as part of the heist plan.  Kid Colt recognizes Riker, and forces the story out of him as they and Rawhide wait in jail. Riker’s trying to get himself thrown in the pen to rescue his kid brother, who’s a convict. When he saw the chance to shangai his old acquaintance Kid Colt into this cockamamie plan, he took advantage of it, landing Rawhide along with him (“Because any friend of Kid Colt is a friend of mine! Right, Kid?!” The trio is sentenced to ten years at the state pen in Yuma, Arizona, with its infamous “Devil’s Dungeon.” Meanwhile, the real culprits receive only six months in the local jail. They find themselves doing hard labor under a brutal guard. The warden plans to teach them a lesson and sends them to the Devil’s Dungeon, but not before telling Riker that his brother Steve is no longer being held: he tried to escape and was shot in the back! The three do a month in the dungeon, and Colt recalls how he and Burt Riker met in Dodge City, when Colt defended the unarmed, womanizing Riker from the bullets of a jealous boyfriend. When Colt and Riker strike camp at a safe distance, Riker reveals that he wasn’t actually unarmed at all—he’s a fast gun, himself, but never kills. Now Colt’s good deed has proven pointless and has earned not only Colt a stretch in the big house, but also his innocent friend Rawhide.  After their stay in the dungeon, the boys are back at hard labor, and Riker assaults a guard who lays a bullwhip on Rawhide, which earns them an even worse fate, left in deep holes to suffer the heat and the tarantulas. When the guard—who has appropriated Colt’s trademark black-splotched leather vest—returns after 12 hours with some water, Colt pulls the guard down into the hole with him by yanking on the rope from which the bucket of water was lowered. Colt regains his vest and the guard’s six-shooter, and uses the guard’s body as a ladder to ascend to the hole’s opening. Above ground, Colt rescues Rawhide and Riker and make their try at an escape. Success seems unlikely, but Riker strikes out across the prison yard, doing a decent turn by making himself the sacrifice that might enable the Kids’ getaway.  Using a rifle as a lever, the Kids manage to unbar the prison gate from the inside. They look back, planning on bringing Riker along. Riker’s on his way, indeed, having eluded capture, but the same guard who killed his brother Steve gets a clean shot, and Riker goes down. The furious warden sends out ten armed men on horseback to bring back the Kids, who are attempting to escape on foot. With no hope of outrunning them, our heroes stage an ambush: when one of the pursuers rides ahead to scout for the fugitives, Colt pops up from under a dug-up bush (!?) and gets the drop on him, while Rawhide gets the drop on his horse, leaping from a perch in a tree. The Kids leave the hapless bounty-seeker tied to a cactus and head across the desert for the border. The horse they’ve taken doesn’t have many miles left in him, and the ten men are hot on their tail (having recovered the tied-up Zeke). Rawhide dismounts, telling Colt he has a plan in mind, while Colt takes shelter behind the prone horse, using its flank to steady his rifle aim. Zeke’s poised to fire on Colt when Rawhide repeats the same trick , dropping from a mesquite tree to take him out.  With that, the Kids have nabbed a second horse and high-tail it for the border, making it over the Mexico line just ahead of the guards. From there, it’s a two-hour trek to the nearest town, where they hit the saloon with a considerable thirst, and surprise, surprise, there’s Burt Riker, trying to explain how he can be holding four aces when the Mexican he’s playing poker was holding one himself! He’s been waiting for his “friends”, having escaped with only a flesh wound, bribing a guard with money hidden in his boot. “I didn’t have enough to buy all three of us out—so I did what I could for you—before getting out myself! Bert Riker always takes care of his friends—right, Colt?!”  Comments Comments: The first page masthead read: “Stan Lee presents: Kid Colt and the Rawhide Kid – Together!” That’s another indication that suggest to me that this wasn’t prepared as a regular issue of Kid Colt Outlaw, since that sort of approach was used on Marvel’s team-up books, and not on solo books that happened to have a prominent guest star. And I think that by the time Giant-Size Kid Colt had made it to its third issue, Marvel had committed to this being their new “Western Team-Up”, just like Giant-Size Spider-Man was really a Giant-Size Marvel Team-Up. And of course, there was no “regular” material being prepared for Regular-Size Kid Colt Outlaw at the time, other than this oddity. For comparison, the masthead for the Giant-Size Spidey that co-starred Doc Savage:  With these last two issues, I’d have to say the western team-ups were on the upswing, getting quite a bit more interesting than the two stories prepared for Western Team-Up itself. Friedrich and Lieber both gave a lot of focus to the supporting character (or, in issue 1, to the brand-new potential lead), making up for the fact that the various Kids in each issue didn’t have a lot of meat on their bones. Murdock, Derringer, and Riker have some character background and undergo some character development on which the stories are hung, while Rawhide and Colt end up right where they started. Friedrich’s stories feel a bit more contemporary to me, incorporating prison brutality scenes that would evoke gritty 70’s cinema, with characters like Striker acting more clearly lascivious toward women than we saw Lily the saloon girl dealing with in WTU #1. This story also has a stronger “cowboy buddy picture” feel than the previous team-ups did, as Colt and Rawhide have to endure a shared misery and cooperate in almost all of the action. Kid Colt, as the titular star, does manage to steal a little more of the attention this issue, being the one with a prior relationship with the supporting character, and earning a personal grudge with the guard that steals his vest. Rawhide is really just along for the ride. Rawhide’s outlaw status makes the plot a bit more workable than it would have been had a more highly regarded western hero been required for plot’s sake to be hauled in to the pen, but there are no significant “character moments” for Rawhide here. And I believe this brings us to the end of the Bronze Age western team-ups. They breathed a little more life into a genre that Marvel couldn’t quite keep alive in an era when superheroes were ascendant. Next, I’ll back up quite a bit, but we’ll eventually make it back into the Bronze Age and cover the team-ups that preceded Western Team-Up #1. [/b]

|

|

|

|

Post by tarkintino on Nov 19, 2020 16:15:59 GMT -5

Kid Colt Outlaw #201, December 1975 Written by Gary Friedrich Penciled and inked by Dick Ayers Artie Simek, letterer Vic Mortellaro, colorist edited by Marv Wolfman Cover by Gil Kane “Death in the Devil’s Dungeon” So, if he's making a reference to the Lizzie Borden case, was this tale set in 1892 (the year the Borden murders occurred) or later? If its that late in the 19th century, it puts a different complexion on this western series, as it would seem the creators could have thought about moving it in the direction of some western serials where territories were still without plumbing and using horses, but early cars were used (for America, that would set the date at 1908 or later). Agreed; after Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid at the movies and Alias Smith and Jones (the TV series inspired by it), western characters were a bit more modern in their characterizations, certainly beyond John Wayne's stiff-backed stroller-types and even "hipper" than an earlier character of that type, Steve McQueen's Josh Randall from Wanted: Dead or Alive TV series (1958-61). This was the direction Marvel western heroes needed to follow, as it made a far more interesting group of characters to invest in, not coming off as well...relics. |

|

|

|

Post by Prince Hal on Nov 19, 2020 16:51:11 GMT -5

Is rascally ladies' man Burt Riker based on Burt Reynolds?  Inquiring minds want to know... |

|