|

|

Post by hondobrode on May 27, 2017 17:29:15 GMT -5

Yes, Tundra felt different, and more expensive, than anything else at the time, like a boutique publisher.

I too remember being impressed with Mike Allred. Madman was really cool. I also remember that Tundra's stock and production values were very high.

Looking forward to more !

|

|

|

|

Post by Reptisaurus! on May 30, 2017 18:35:54 GMT -5

Man, I've been reading this thread for over an hour now.

You are really close to having a book, here.

|

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on May 31, 2017 0:40:29 GMT -5

And I haven't gotten to Kitchen Sink, Aardvark-Vanaheim, Fantagraphics, Renegade, Slave Labor Graphics, and Last Gasp yet; let alone Dark Horse and Image! There's still some top self-publishing ventures and some imports, too (Dargaud USA, Catalan Communications, NBM, Platinum Editions). Oh, and there's Malibu (et al), Apple, Vortex, Valiant, Defiant, Broadway, Claypool, Topps, Tekno, Hero, Caliber, Fleetway/Quality/Etc (with UK reprints, like Judge Dredd, Slaine, and New Statesmen). Book? I'm going for a set of Encyclopedias!!!       |

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on Jun 4, 2017 18:59:40 GMT -5

Another pair of high profile releases from Tundra involved Dave McKean. McKean crossed the ocean to New York, where he made the rounds of the big publishers to show his work. This led to working with neil Gaiman, producing the Black orchid mini-series and the covers on Sandman, as well as drawing Grant Morrison's Arkham Asylum. The collaboration with Gaiman led to a short work, Violent Cases, in 1987.  The book was originally put out by Escape books and was then reprinted by Tundra. When Gaiman met with Tundra about doing the reprint, he was the rising star of comics, the Second Coming of Alan Moore, in many critics eyes (despite the differences in their writing styles and the types of stories they did). Gaiman knew the value of his name and he negotiated accordingly. According to the Comics Journal interview with Steve Bissette, Kevin Eastman had hoped that Gaiman would do more for them and Gaiman was cagey enough not to do that. Gaiman was experienced in the world of publishing and he treated the arrangement as business. Apparently, there was a bit of friction, as Tundra's aspirations didn't match Gaiman's. Still, Tundra helped bring Violent Cases to a wider audience. The story revolves around a narrator, who looks like Neil Gaiman, who describes an incident when he was young, where his father was trying to drag him upstairs to bed and the boy wanted to go back downstairs and the father tugged too hard and dislocated his arm. The father takes the boy to see an old osteopath, who turns out to have worked for Al Capone, in America. What follows is a juxtaposition of stories of Capone's violence and violence within the boy's world, whether from his father, other adults, or children. It's done in stark, subdued colors; almost black & white. Like much of Gaiman and McKean's work, it revolves around dreams and nightmares and it looks like something out of a dream or nightmare.    It's not for everyone. In many ways, it is darker than most of Sandman (which I would argue lost much of its darkness as it became a hit). It's not my cup of tea, nor was Mr Punch, their later collaboration. My brain can conjurer enough nightmares without Gaiman and McKean providing material. Cages I've never actually seen, nor do I have scans. This was McKean on his own, and his style is more basic and draws from elements of Latin artists Alberto Breccia and Jose Munoz, as well as Italian Lorenzo Mattotti.    Cages ran into the Tundra implosion, after 7 issues and was finished up at Kitchen Sink after the merger. It's still a bit of a cult book that only the faithful hunt down. Next, the last major prestige project from Tundra and the one that has had the longest lasting impact. |

|

|

|

Post by hondobrode on Jun 4, 2017 22:28:24 GMT -5

Looking forward to this next thang, which it took me years to finally get...

|

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on Jun 7, 2017 13:27:21 GMT -5

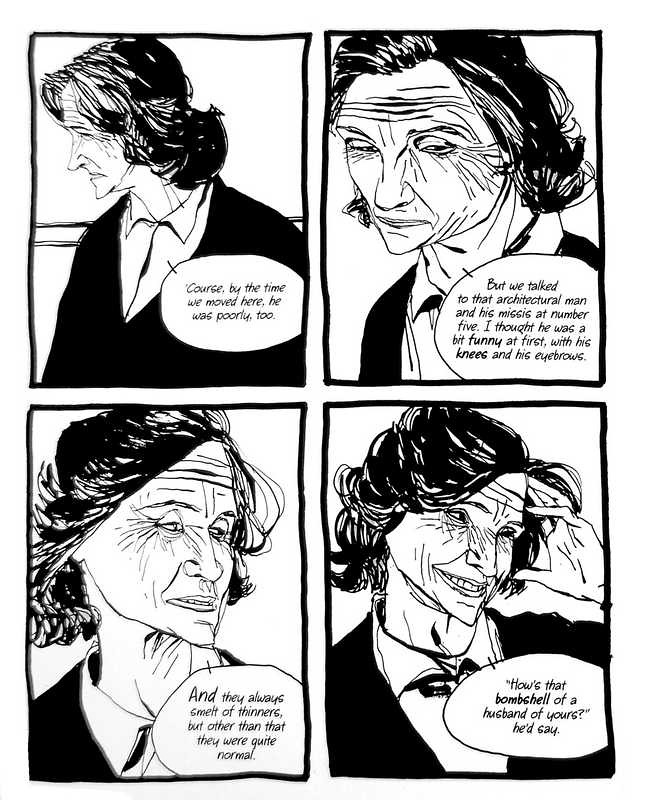

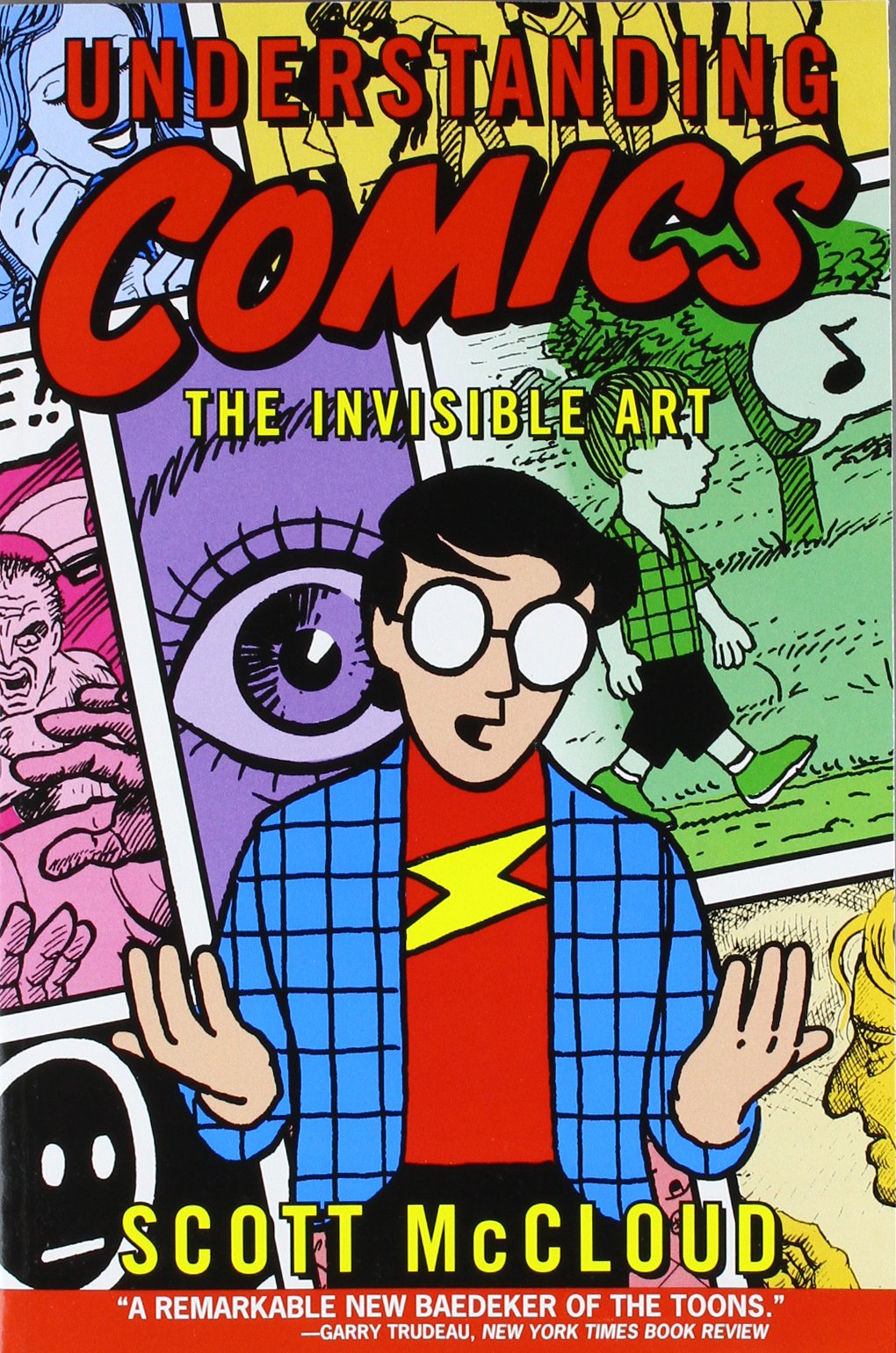

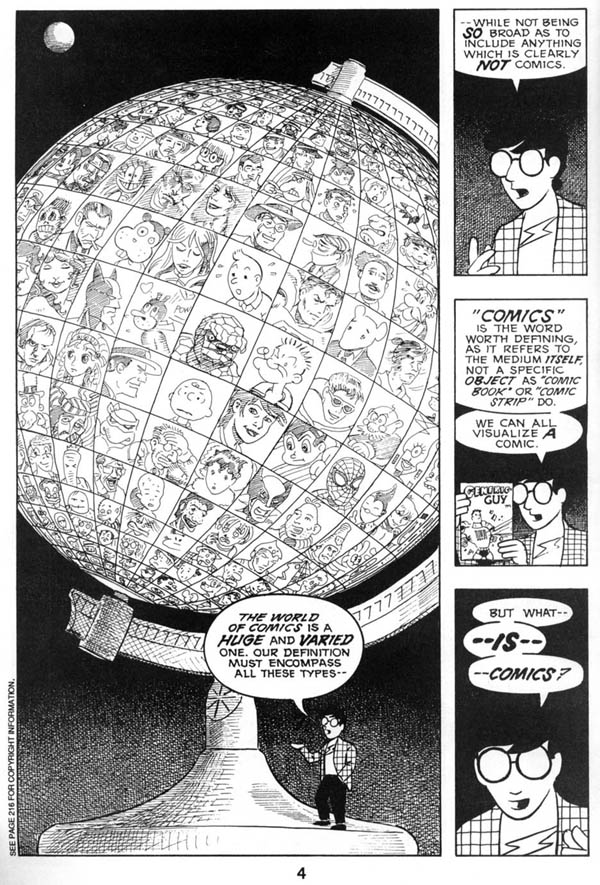

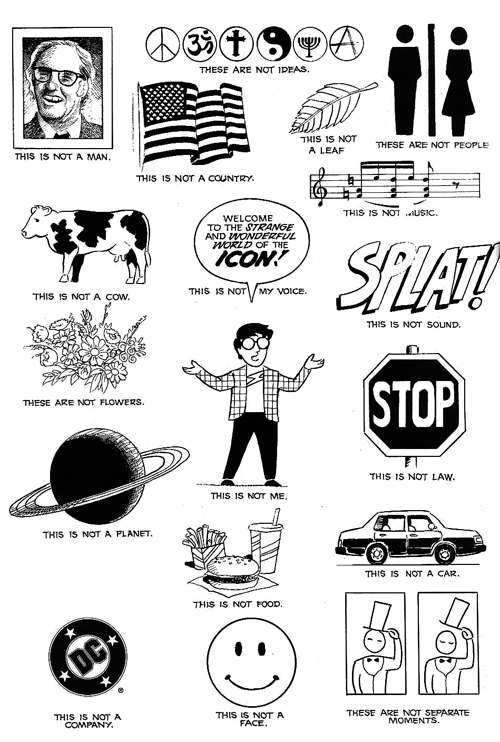

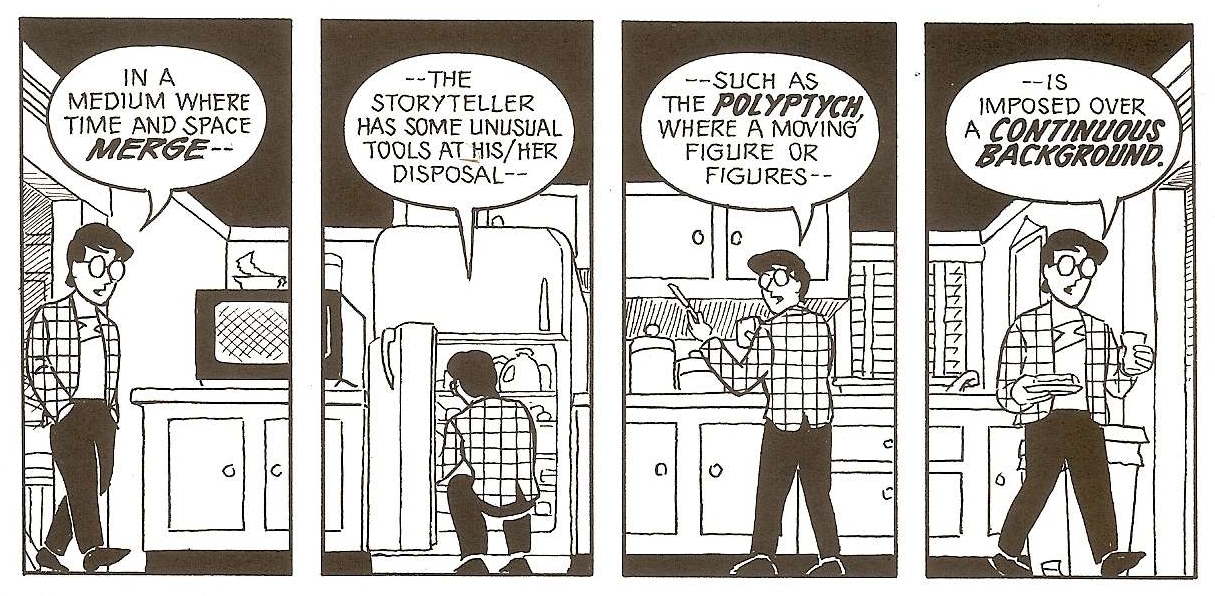

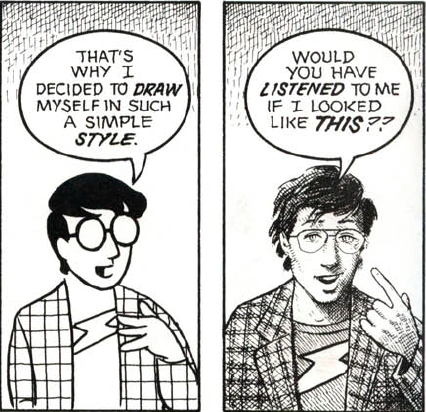

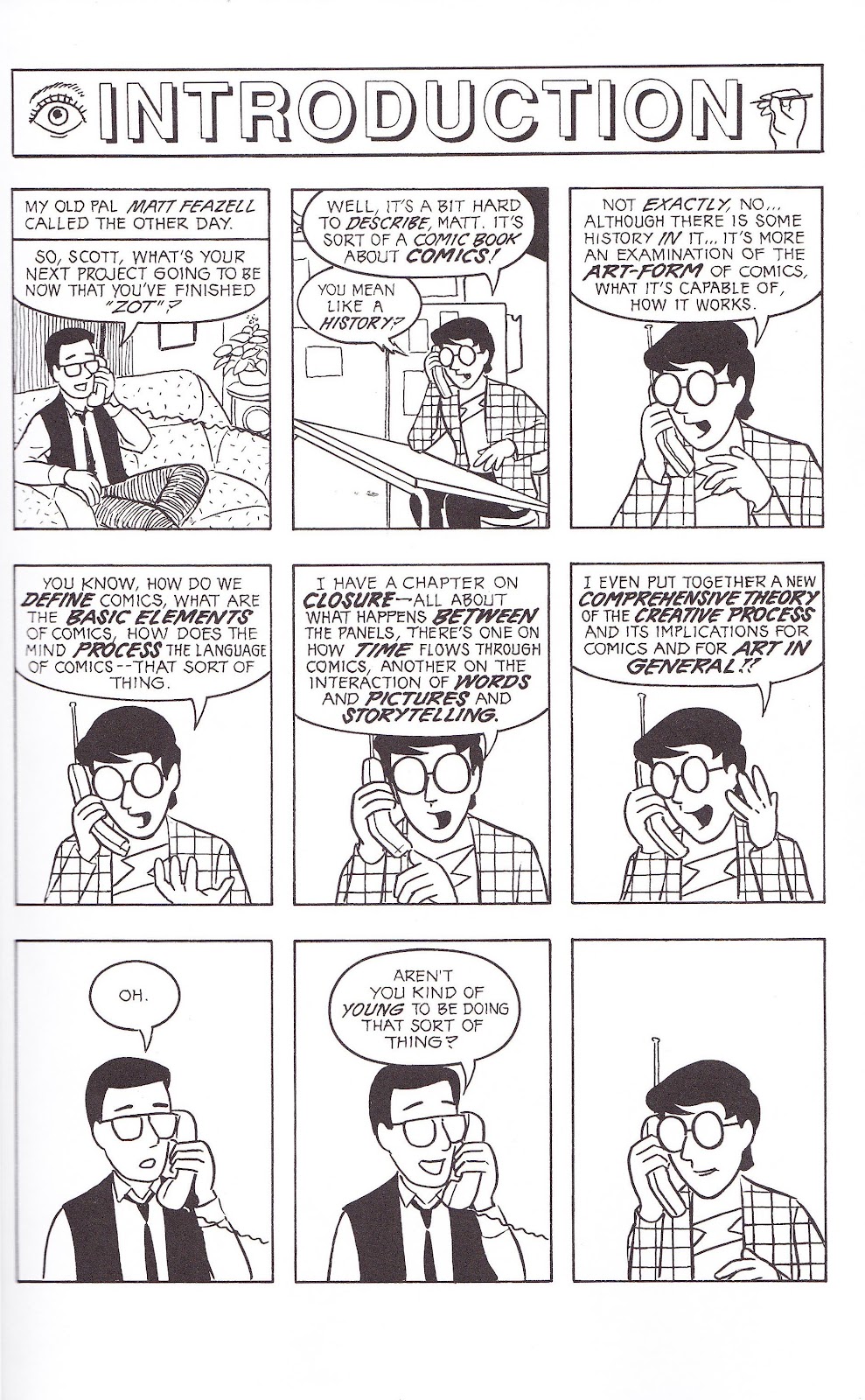

We now come to our last look at Tundra and the project that arguably most fulfilled their goals of publishing high quality material and providing a mechanisms for talented creators to produce their dream projects, without commercial considerations: Understanding ComicsNow, when most of you think of the book, I suspect your image is this:  This is the version most people have seen, from Harper Collins, found in most major bookstores' graphic novel section. When I think of it, I think of this:  This was the original Tundra edition, complete with their Mammoth icon (something which appears in the book!). I can't recall if I saw this in Advance (Capital City's order book) or in the Bud Plant catalog; but, I got it as soon as it came out. I had resigned my naval officer's commission and had looked at trying to become a comic book artist. I had applied to and been accepted at the Kubert School. I was reading and using every book I could find about cartooning and comic book art and storytelling. There weren't many. I had all of Burne Hogarth's Dynamic Anatomy books, which weren't exactly great instruction, as much as a showcase for Hogarth's art, with his thoughts. Some elements were more useful than others, while parts of it made me feel insecure about my art.  I also had How to Draw Comics The Marvel Way, with Stan Lee and John Buscema. It was a good starter book, with helpful hints about anatomy, foreshortening, composition, points of view and the bare basics of storytelling. However, it didn't go very deep and it only took me so far.  One series of books proved very useful, from Jack Hamm.   These were excellent instruction books, with more detailed techniques for achieving both cartoony and realistic art. They covered things like perspective and proportion, light and shade, texture, hair curls, bodytypes, elements of expression and more. These really helped me, especially in drawing more realistic proportioned characters and clothing. There was still an element missing, though, which was storytelling in comics. For that, there was really only one book:  Comics and Sequential Art Comics and Sequential Art is by Will Eisner. of course it is; who else treated comics as serious art, so early? Eisner first published the book in 1985 and it sets down his ideas about the storytelling mechanisms of comics. He looks at things like light and shade, point of view, etc; but, he also talks about how body language can convey ideas, how to use key scenes to tell a story, how to establish mood, etc.. These were the elements that helped turn comic drawing into comic book stories. So, what was so different about Understanding Comics?  The book is Scott McCloud's thesis about how stories are conveyed by the mechanisms of comics. It is filled with examples of how iconography conveys information, how our brains work with the layout of comic panels and also how these mechanisms have been used around the world.  McCloud opens by defining comics and what separates them from just illustration and animation. He establishes a vocabulary for comics and then shows how our brains respond to that vocabulary. He then moves beyond into how time works, how lines affect perception, how color can work and how to link all of the material into actual comic stories. He looks at historical examples of graphic storytelling, such as ancient pictograms and hieroglyphics, the Bayeux Tapestry, the works of William Hogarth, proto-graphic novels (like Rudolphe Topffer) the early recurring comics (like Alley Sloper and Max und Moritz), the classic comic strips and comic books. Throughout, McCloud mixes both an academic and a playful tone. However, another element that sets it apart from Eisner and the art books of Hogarth and Hamm is that it is done entirely in sequential art; it's a graphic novel about how graphic novels (comic books, manga, bande desiness, fumetti, whatever you want to call comics ) tell stories.    Now, I had been studying comics for a bit, so some of this material seemed a bit old hat. For instance, I knew how you could expand or contract time, depending on the number of panels you use. However, the concept of closure was a new idea for me:  Closure is all about how your brain fills in the gaps between panels. Comic panels show you moments in time;yet, somehow, your brain fills in the sequence of actions that take you from one panel to the next. It never struck me before. In animation, they have what is known as "in-betweening"; the sequence of movements that link the key scenes. Animation directors usually laid out those key moments, then "in-betweeners" drew the tedious drawings that moved the character from point A to point B. Closure does this in our brains, when we read a comic. Our brains do the "in-betweening". It is for this reason that an artist must be careful in which scenes he/she choose to depict. If they choose the wrong moments, our brains have trouble filling in the details. If they use too many or too few moments, it alters our perception of time. If it all sounds rather academic it is; and it isn't! McCloud has fun with it and recognizes when he's getting a bit too pompous and throws in a bit of humor:   Heck, the introduction helps set the dual tone of academic and playful:  The legacy of Understanding Comics is tremendous. The book transcended the world of comic distribution and became a mainstream academic work; a seminal work on the history and critical look at pop culture. It became a standard item in bookstores and libraries around the country and around the world. It won both the Harvey and Eisner awards. A swedish edition won the 1996 Urhunden Prize. The French edition won the Prix Bloody Mary (comes with a celery stalk!  ) at the 2000 Angouleme festival (one of the premiere comic festivals in the world). It is THE textbook for the aspiring comic artist. When I was a bookseller, there was nothing more satisfying than seeing someone looking at the book and seeing it in school libraries, when I visited to consult about graphic novels (my favorite duty, as a bookseller). The book had a modest release, which quickly snowballed into full-fledged star status and a visibility that most publishers would sacrifice their children to achieve. And, through it all, Scott McCloud has been a wonderful ambassador to the rest of the world, for comics. That is Scott McCloud's legacy and it is Tundra's legacy. |

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on Jun 7, 2017 14:12:36 GMT -5

Coda So, Tundra began as Kevin Eastman's attempt at producing quality comics, without profit motivation and to provide a structure that would allow creators to produce their dream works, without being beholden to commercialism and large publishers. It was a noble idea that was probably destined to fail. For one thing, Eastman was never really able to define what he wanted Tundra to be, beyond those vague philosophical ideas. For another, he let his enthusiasm for the idea outstrip his common sense. Steve Bissette detailed his experiences with Tundra in an interview with the Comics Journal (issue #185).  He describes a rather chaotic atmosphere, with too many indians and no chiefs. Eastman didn't want editorial interference and had no editorial department. While that took limits off of creativity, someone actually has to do the work of getting the book printed and published. That is the job of an editor. Some of these duties were covered by other people, who developed their own little fiefdom within the company. Sometimes, their point of view was at odds with others in the company, including Eastman. Bissette says that Eastman wanted to start small, with just a handful of releases, then came back from the San Diego Comic Con with 70+ projects that he had signed up! It was madness. Bissette describes some as having taken advantage of Eastman's generosity and then not producing the work; they took the money and ran. Others produced at such a slow rate that it took forever to release it. He talks about competing agendas when Eastman negotiated with Neil Gaiman, who was rather shrewd about his "brand." He describes how Eastman produced a digital production set up, then made it exclusive to Tundra's use. The operation used to do work for other ventures; but, by making them exclusive, they lost large revenue streams and Tundra couldn't provide enough publishable work to keep them busy. Eastman poured money into it, before shutting it down and laying off employees. Morale went in the toilet. before it was all said and done, Eastman had pumped something in the neighborhood of $14 million into 3 years of Tundra! Even for someone with Turtle Money, that was significant. Eastman decided to cut his losses and put Tundra to sleep. However, he didn't exactly shutter the operation. Instead, it was announced that Kitchen Sink had bought Tundra. This was stunning to the comic world and didn't quite make sense. Kitchen Sink was a fine operation; but, no one believed Dennis Kitchen was raking in the dough publishing Omaha the Cat Dancer, The Spirit reprints, Flash Gordon collections, and Cherry Poptart. Something didn't add up; Eastman was the one with the FU money. It later emerged that Eastman actually bought an interest in Kitchen Sink, while Kitchen maintained majority ownership. However, Eastman's Tundra projects became priorities for Kitchen Sink as they continued and finished such projects as From Hell, Maximortal, and Cages, and then published scheduled, but uncompleted works, like Eastman's own Melting Pot, with Simon Bisley. It seems though, there were certain expectations with Eastman's stake and that he didn't quite meet them and his stake in Kitchen Sink was reduced, over time. Eventually, Kitchen Sink ran into hardship, due to the fallout of the Distribution Wars, touched off when Marvel bought Heroes World and made it its exclusive distributor. Kitchen sold Kitchen Sink to a media group, who wanted it for The Crow and other properties that might be exploited for movies. In the end, Kitchen Sink was shuttered, another casualty of the 90s chaos. Kevin Eastman concentrated his energy on Heavy Metal, which he purchased around the same time that he set up Tundra. He was more successful with it, though nowhere near the success of the glory days of the magazine's earliest years. The magazine, which had always mixed sci-fi and fantasy with erotica, became increasingly focused on sex and horror, and showcased fewer and fewer high profile European works and more an more work from artists like Serpieri and less high profile contributors. Eastman sold the magazine a couple of years ago. In between, Eastman sold out his shares in Mirage and the Turtle franchise. Peter Laird maintained his involvement until 2009, when he sold all rights to Nickelodeon. In an apt metaphor, Tundra saw only brief light of day, before returning to the ice; but, that light shown very brightly. It did much to show the rest of the publishing world what comics could be, which did much to draw interest from mainstream publishers, which helped present new avenues for creators to pursue. Had it not occurred, Akiko, on the Planet Smoo might have been just a cult comic book, rather than a successful series of children's books. Same with Scary Godmother and, perhaps, even Bone. Would Paul Auster's City of Glass been adapted by Paul Karasik and David Mazzucchelli and published by Avon? Would Chris Ware have become the darling of the literary world? Well, maybe; but, maybe not as early as they did. Certainly, companies like Fantagraphics and Kitchen Sink, as well as individuals, like Art Spiegelman were working in the same avenues. However, Tundra concentrated those efforts into one package and threw a ton of money at it. It's results were few, but far reaching. |

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on Jun 7, 2017 14:24:55 GMT -5

ps

I never got to go to the Kubert School. At the time, the cost was something like $11,000 a year and I was not eligible for the GI Bill (the Navy paid for my Bachelor's Degree, up front), nor did I qualify for financial aid (military salary and benefits skewed the computations too much). The idea of loans was unthinkable, as I had existing debt to pay off; so, the dream didn't happen. Looking at it objectively, I doubt my art would have risen to the level to get me into the comic book world; I started focusing on it too late and had a long way to go. Still, the school was intensive training and who knows how things might have developed? Instead, I continued to be a fan and advocate, who spent 20 years as a bookseller, sharing that with customers. That was the most satisfying aspect of my time at Barnes & Noble, before their struggle to stay alive sapped the fun out of it. This is part of why I run off at the keyboard here; it's my outlet for sharing my love of comics.

|

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on Jun 9, 2017 21:37:10 GMT -5

If Tundra was the Rolls Royce of comics, then our next publisher was more of a Ford Focus, with a spoiler.  AC Comics, which, yes, it's still alive, is the oldest independent publisher in comics (depending on how you view Archie), having begun in 1969, as Paragon Publications. The company is the brainchild of fan/historian/writer/artist/publisher/chief cook & bottle-washer Bill Black. Essentially, it was another fanzine publisher, until 1983, when it started to produce full color comics on a regular basis. Now when you think of AC, a few things may come to mind...       and  From the start, Paragon Publications published cheap black & white superhero comics, like Paragon Presents  and black & white reprints of Golden Age comics, from defunct companies...  Their material appeared sporadically, averaging about 3 titles per year, since Bill Black was pretty much a one-man operation. In 1983, Paragon changed its name to Americomics, to provide an umbrella title for its material, rather than have several, infrequent books.  in 1985, it started its longest running series, Femforce..   By 1984, Americomics was calling itself AC Comics and it has remained thus, ever since. Over that time, they have drawn criticism for objectification of women, via cheesecake covers and interiors, low rent production values, and cheesy writing. It's kind of hard to say you are a serious publisher with books like this...  However, the saving grace for AC has always been the attention they have thrown on Golden Age comics, from the lesser publishers, in affordable packages. Being able to see Jerry Robinson & Mort Meskin art, Lou Fine stories, Matt Baker Phantom Lady strips, Dick Ayers Ghost Rider (the Magazine Enterprises original) and Avenger (an ME superhero title), some Catman comics, Crimebuster stories (including a whole collection of stories with Ironjaw) absolves a lot of sins. At its heart, AC is much like Golden Age publishers Fiction House, Fox, and Lev Gleason; they aim a little lower, have cheaper production values, but still have an enthusiasm to their stories. It's not all cheap T&A or old Golden Age material and I will also highlight some of their other homegrown characters, including Captain Paragon and The Sentinels of Justice, as well as the Femforce and the various Golden Age reprints. There's a lot repetitive product from AC, so I will stick to the unique and the highlights, as well as a few of their other ventures. Y'all come back now, ya here?    |

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on Jun 10, 2017 15:05:35 GMT -5

So, as I said last time, Bill Black and Paragon started out doing black & white fanzines, with some comic stories mixed in.    From the start, the focus was on Golden Age mystery men and women, jungle girls (especially Sheena and Nyoka, and western heroes, especially the Republic bunch and those of the early 50s. Black was also a fan of old horror movies and those elements mixed into his comics. When he started Paragon, he was also doing some work for Warren and even worked a bit with Roy Thomas, at Marvel In fact, the What If? issue, with the 1950s Avengers (3-D Man, Marvel Boy, etc...) that inspired the Femforce. Black had suggested an all-female team of Timely's heroines, but Roy shot it down. Within these fanzines, you could find reprints of things like old Sheena comics, as well as new characters, like Captain Paragon, the Shade, The Girl from LSD (later renamed Synn) and Tara, the Jungle She-Cat. The artwork was a bit crude, as it often was in fanzines. Paragon also produced some portfolios...  Paragon Golden Age Greats features art from Black, Dan Adkins, and Don newton, as well as a piece by Tom Fagan, the host of the Rutland Halloween parties that turned up in Marvel and DC comics. It also shows Black's tendency to push a good thing a little far, as his pin-up of Harvey's Black Cat features her being tied up by a dominatrix-looking woman, with exposed breasts (nipples covered Wendy O Williams-style). Damsel-in-distress imagery was part of pulps and comics, though this was a bit on the trashier side. In 1983, Paragon became Americomics and launched some full-color comics, including one titled Americomics.        Issue one features a cover by George Perez, with an interior story of The Shade, by Bill Black. The Shade fights within the dream world and is one of Black's oldest characters. his early appearances featured a standard superhero suit; but, he's upgraded into a more supernatural figure here. The story is not Alan Moore; but, it's fine, for this type of thing. Issue 2 features The Messenger, with story and art by some rookie, named Jerry Ordway. It's definitely not the Ordway we would come to know; but, there are signs of that talent, here and there. We also get another Shade story, where he must face The Terror, who is a version of the Nedor hero The Black Terror (a favorite of Black's). Issue 4 features an Ordway cover (his skills showing great leaps), with a story inside about a woman who accidentally intercepts a bolt of mystic power, turning her into a superhero, Dragonfly. Her life is a little heavy on the soap opera (and it's pretty cliched, though slightly satirical stuff) and the action isn't as well staged as the cover shot. Issue 5 gives us Captain Freedom, the protector of an underwater city. Art is by Vic Bridges, who appears to be heavily channeling John Byrne. Issue 6 is another old Black character, the Scarlet Scorpion (essentially, a Blue Beetle swipe). Wait, you skipped issue 3! Well, I'm getting to that. Issue 3 features the Blue Beetle; both of them (Dan Garrett and Ted Kord). Meanwhile, the Americomics Special features the Sentinels of Justice, a team composed of the Charlton Action heroes. How the heck did this come about? Well, Bill Black had also been involved in the Charlton Bullseye crowd and published some work there. When Charlton went belly up, Black published some stuff that had been intended for the revived Charlton Bullseye, which leaned heavily on amateur fan material. Guys like Bob Layton had seen their work printed in this method and this was more of the same. Americomics 3 has a Pat Broderick cover, but Rik Levins and Bill Black provide the interior story. The material indicates it is copyright Charlton and used by permission; so, Black was legitimately publishing this. Same with the Americomics Special, which has a story where The Question, Blue Beetle, Captain Atom and the Nightshade are teamed up as the Sentinels of Justice. Nightshade even gets a new costume and they face The Ghost, a villain from the Charlton stories. However, as the Special was printed, DC had finished the purchase of the Charlton Action Heroes (minus Peter Cannon, who was owned by Pat Morisi). Black makes note of it in the book and previews a new Sentinels of Justice, featuring his own characters. Atomic Mouse, another Charlton property, also made an appearance in issue 4.      AC published various comics with their homegrown heroes, including Captain Paragon, Scarlet Scorpion, Colt, Tara, Nightveil, Bolt and Starforce Six, Dragonfly and others. Most looked rather amateurish, next to DC and Marvel (heck, next to Eclipse and Pacific) and they never set the world on fire. Because of the heavy T&A element, the females did better, which we will get to in a bit. One book stood out a bit.      Black Diamond featured the adventures of Tiana Mathews, a globetrotting model who is secretly the Black Diamond, an agent of the spy organization Info Com 3. She deals in events surrounding the shady QUANSA organization. The story and art were a cut above a lot of what AC had been doing and the plot was more exciting. It was also different, mixing Marvel's Black Widow and the British Modesty Blaise, with a little Nick Fury, Agent of SHIELD for good measure. It didn't go overboard on the T&A, though it is there. Instead, it features a tough, capable female character kicking butt, with guns ablazin'. It was allegedly based on a movie in development, to star B-movie actress Sybil Danning (Battle Beyond the Stars, The Three and Four Musketeers). No movie ever came out. A graphic novel was promised, adapting the screenplay. Somehow, I suspect there was some conning going on here, or at least delusions of grandeur. Black said Danning got in touch after her agent saw a piece in Bill Black's Fun Comics, about Sheena and it mentioned the new movie (which was eventually made with Tanya Roberts) and thought Danning was perfect for it. Danning was put in touch with Black, who passed on info and she put him in touch with the Black Diamond writer/producer, Mike Frankovitch. The comic was the result. The awesome Gulacy covers on the later issues (Black did the cover of issue 1) helped sell it more than most AC books. It's a shame he didn't do the interior, as well. Danning was featured in photos and pin-ups, to help sell the book. As you can see, much of the AC model was professional or semi-professional covers, with amateurs on the interiors. The end result was mixed, with enthusiasm making up for skill, in some cases, and just overblown fan projects in others. This trend continued, as AC's covers were often superior to the interiors. That, except for the Golden Age material.    Black continued producing fanzines, with Bill Black's Fun Comics. Like the older Paragon material, these were a mix of articles, Golden Age reprints, fan pin-ups, and new material. Black reprinted some Matt Baker Phantom Lady comics, from Fox, thinking the character was in the public domain. The Fox stories were; but the name was owned by DC comics, via their purchase of the Quality Comics version. They soon exerted their rights and Black started calling the Phantom Lady the Blue Bulleteer, when he used her in other comics. That character grew into Nightveil and would be part of the Femforce. meanwhile, we got more Captain Paragon and the Shade and others. Next, we will look at the Golden Age western comics that AC put out, an area that made them completely unique in the comics world of the 80s and 90s. |

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on Jun 11, 2017 21:47:22 GMT -5

One of AC Comics more unique offerings, especially in the 80s and 90s, was its reprints of old western comic stories. Bill Black was a film collector and old westerns and western serials were favorites, especially the Durango Kid and Roy Rogers. he was also a big fan of Dick Ayers work on the original Ghost Rider, from Magazine Enterprises (ME).    If you've never seen these stories, you are missing out! Ayers knocked out some doozies, in the 14 issues ME published.  Black first started reprinting these in Macabre Western  Ghost Rider was re-christened The Haunted Horseman, to get around Marvel's trademark; but, the stories were all Ayers. Well, apart from a few where Bill Black added some scenes, with obvious added artwork. He also published stories with Tim Holt, the western movie actor, also from ME. He added others that were produced by Fawcett and Charlton (who picked up some of Fawcett's western and other genre comics), including some Alan "Rocky" Lane comics, that were drawn by Dick Giordano. He also added (with permission) Roy Rogers, reprinting those old comics. Much of it appeared in the anthology series, Best of the West.        as well as individual reprint titles...          AC's Golden Age Greats and Golden Age Great Spotlight also had a collection or two of these stories:     If you love westerns, you would do well to seek some of this material out. The reprints are in black and white and AC packed each comic and trade with plenty of good material. In the late 40s and early 50s, the western comic ruled the stands, as it did the Saturday matinees and early tv. Some of the best artists in comics worked on them and Black gives them all some love, coupled with articles about the comics, the film stars and the film series, which can steer you to some of the celluloid fun. |

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on Jun 12, 2017 23:07:05 GMT -5

Well, let's get to the heart of AC Comics: the Femforce. As far back as 1971, Bill Black's Paragon was publishing fanzines with superheroine pin-ups and stories.  There was a lot of T&A and some nude and semi-nude pin-ups; some playful cheesecake (like RC Harvey's work), some borderline pornographic, some just tributes to great female characters. Characters like Sheena and Phantom Lady were great favorites and they appeared in reprints of their stories. While Bill Black worked with Roy Thomas, on What If?, he suggested a team of Timely's heroines, which Roy shot down. He decided to do it on his own. He first tested the waters in 1981, with the Femzine.  The team there was Synn (aka The Girl from LSD), Tara (the Jungle She-Cat), Phantom Lady (the Matt Baker version, from Fox Comics) and the Blonde Bomber (a Black Canary pastiche). The magazine featured a story with Femforce One: The All-Girl Squad, a tribute to Irish McCalla (the tv Sheena), reprints of the Phantom Lady, Sheena and Spy Girl, and some pin-ups (of course). This was followed by the Femforce Special, where the ladies fought Lady Luger...  ...because you need a Nazi dominatrix for these kind of things! After DC warned them off the Phantom Lady name, AC called the character the Blue Bulleteer, who morphed into Nightfall, then was renamed Nightveil. Added to the team was Ms Victory, aka Joan Wayne. She was an update of an obscure Golden Age character, Miss Victory, from Helnit Publishing, which was bought out by Holyoke (publishers of Catman). Also joining the team was GA comics heroine Rio Rita (also star of movies) and She-Cat (a pastiche of Harvey's Black Cat). The light-hearted story was filled with boobs, bondage, and brawls. If it sounds like AC was aiming at the lowest common denominator, remember that many a comic company used the same themes to sell comics. Fiction House and Fox made an entire publishing line based around these facets and even the bigger houses tread these waters. Wonder Woman, in the 40s, was as kinky as it got. Black Cat was filled with judo and deathtraps. As Black like to point out, it was no worse than tv shows, like Charlie's Angels, where camera shots of breasts and behinds were quite common. The tone was light, with tongue firmly in cheek and other parts thrust here and there. A series followed, which is still going (currently at issue #178).        In the 90s, AC followed the trend and had models dressed as some of their characters at conventions. They even produced low-budget movies with the heroines, which they sold via their website and mail-order. In the late 90s, as the Bad Girl fad was in full swing, and things like Verotik and other pron comics were on the stands, AC pushed things a bit further than cheesecake and pulp thrills. Some of their comics got into other fetish territory, like Big Uns, with giantesses and new issues of Femzine, that got borderline pornographic (at best). Included were some scenes with the Blue Bulleteer that were pretty much rape poses, minus the actual act of rape. It was pretty sleazy and didn't do much for AC's image. They published a Femforce Pulp Portfolio, which mostly consisted of a female military character in bondage scenes, being rescued by the heroines. This was a far cry from Good Girl Art Quarterly, where they had pin-ups and adventures, plus reprints of GA "good girl" cheesecake comics.     It's hard to fault AC too much, when you had the likes of Jim Balent's Catwoman and the Milo Manara Spider-Woman cover at DC and Marvel (respectively). AC was catering to their audience. If nothing else, they were using a model similar to Fantagraphics, whose Eros Comics line helped fund the publishing of more artistic work, like Love & Rockets. For AC, Femforce paid the bills that allowed the company to put out Best of the West and Golden Age Men of Mystery. The latter is part of our wrap up, as we look at AC's reprinting of Golden Age mystery men. |

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on Jun 14, 2017 11:09:35 GMT -5

You know, a guy can only "read" so many comics with skimpy costumes, bondage imagery, and cheesecake posing; what else does AC have? Well, how about some of the coolest Golden Age stories you haven't seen reprinted ad nauseum?             Sure, DC reprinted Captain Marvel; but what about Ibis, Mr Scarlet and Spy Smasher? Alan Moore used "The Terror" in Tom Strong and Terra Obscura; but what about the original? Who the heck is Captain Flash? Wanna seem some Lou Fine artwork? Reed Crandall? Dick Ayers before Marvel? Heard about Mort Meskin but have never seen his work, since DC doesn't reprint much Johnny Quick> Want some non-Batman Jerry Robinson? Did you know the creator of the soap opera newspaper strip Apartment 3-G used to draw the Quality Comics Manhunter? Where can I find stuff like that? At AC! AC had been publishing Golden Age westerns material and "good girl" comics since the start, while doing the odd article and pin-up of others. Slowly, they started using public domain characters, like the original Lev Gleason Daredevil (the one with the mixed up suit and spiked belt) and gave them new names (Reddevil). They had reprinted plenty of Matt Baker Phantom Lady and the jungle adventures of Sheena. In the 90s, they started to broaden their horizons. By the mid-90s, several publishers started to latch onto the fact that DC and Marvel didn't own a lot of old superheroes. Malibu published The Protectors, with a bunch of old (and I mean old) Centaur Comics characters, Eclipse had revived Airboy and a new Black Terror, the aforementioned Terra Obscura heroes from Tom Strong (from the Nedor line of comics). They started to realize that the material was public domain, even if some of the names had been trademarked. AC capitalized on this and gave us economical black & white reprints of all kids of stories. Black had his favorites, so we got the umpteenth Matt Baker Phantom Lady; but, he also liked the Black Terror and we got to see all of the Mort Meskin & Jerry Robinson stories (really, the only ones of merit) as well as their work on Fighting Yank. He had been publishing Dick Ayers' Ghost Rider (as the Haunted Horseman) and now gave us his work on the Cold War hero The Avenger (complete with his pogo plane!). There was Captain Flash and Skyman, Captain Midnight, Senorita Rio, Crimebuster, Catman & Kitten, Rocketman (not the Republic serial hero, a guy in a yellow suit), and more. After probably checking with a lawyer, he started reprinting Fawcett material, except for the Marvel Family. He reprinted the Sentinels of Justice story, where the Fawcett heroes team up; but, removed Captain Marvel Jr. he then turned his attention to Quality Comics. DC owned the characters; but, not the stories. So, AC reprinted them. Quality had some of the best art of the 40s and it was given a chance to shine" Lou Fine, Reed Crandall, Alex Kotzky (creator of Apartment 3-G), even some Jack Cole. They stayed away from Plastic Man, the Marvels, and a few others. No Submariner or Human Torch; but, some Hydroman. If you really want to see comics history in the stories that were told in the past, you really need to hunt these down. However, they quickly acquired collector prices, as they were the "archive editions" of the Other Guys. AC also published some of this in larger formats, especially the Golden Age Greats line...     These were square-bound books, with specific themes, in black & white, with accompanying articles. The first one I bought was a collection of Senorita Rio, then the Phantom Lady (or Lady Phantom, as they put on the cover). This one turned out to be one of my favorites...  It features all of the major battles between Crimebuster and Ironjaw, one of the scariest villains of the Golden Age. The art is Charles Biro (and his shop), so the quality is excellent. If you love the Justice Society and the Invaders, you would do well to check out their neighbors from Fawcett, Quality, Heroic, Holyoke, Fiction House, Fox, Nedor, Centaur, Lev Gleason and others. A lot of that material is now available at the Digital Comics Museum ; but, it wasn't then, and, if you like holding paper in your hand, these are way cooler! So, that is pretty much AC. They also put out some amateur videos of people dressed as their characters, as well as old movie serials, and a bit of merchandise. They've just started a new venture with the Neo Charlton people to publish their stuff, including The Charlton Arrow (with an all new Nicola Cuti & Joe Staton E-Man story!) and Crypt of Horror, reprinting old Charlton horror comics. AC has been around for nearly 50 years, outlasting the speculator boom/bust, the Distribution Wars, the Digital Age and online access to free porn; and, they still show no sign of slowing down. When you are in the Old Folks Home, yelling at the nurse to find that copy of Inferior 5 from the long boxes filling your room, you will still probably be able to read a new issue of Femforce and a reprint of a 1940s comic. Heck, they may be reprinting old Silver Age material, by that point (MF Enterprises, Harvey, Mighty/Red Circle, Tower)! |

|

|

|

Post by MDG on Jun 14, 2017 11:25:46 GMT -5

How was the reproduction on the AC Golden Age reprints? I bought similar things by Pure Imagination and other publishers and the quality was often hit 'r miss.

|

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on Jun 14, 2017 13:17:32 GMT -5

How was the reproduction on the AC Golden Age reprints? I bought similar things by Pure Imagination and other publishers and the quality was often hit 'r miss. Generally speaking, pretty good. I don't recall any specific issue I had that had major problems. I had the Pure Imagination Lou Fine Treasury and it was a little light on the blacks; but, AC's reproduction of Meskin & Robinson reproduce those pretty well, without getting murky. The odd story here or there might be a little light; but not distractingly so. Black had been doing this a long time, so I think he had a pretty good handle on the technology to get a quality product, for the money. They weren't as sharp as those Fantagraphic EC books; but, they were about as good as your average DC Bronze Age reprint, in the 100 Pg comics (minus the color). The binding on some of those Golden Age Greats books wasn't the greatest, since they were glued. I've had similar problems with trades from DC and Marvel and a lot of big name book publishers. In the effort to cut costs, publishers have used some sub-standard printers and the quality of the binding is below the standards of even the 50s and 60s paperbacks. You can flip through an old Avon or Dell paperback of that era and have it still be solid, yet 100 pages into a current book and your cover may start to fall off. The Golden Age Men of Mystery comics were all saddle-stitch stapled, as I recall (I have scans, now). |

|