|

|

Post by String on May 9, 2017 13:46:10 GMT -5

Playing catch-up reading here but have really enjoyed your focus on the indie publishers so far.

Back then, my LCS (which was mostly a used bookstore that sold comics and back issues as a supplement) didn't carry all that many indie publishers, certainly not Eclipse. I had heard of them of course but little opportunity to actually read them. Thus, my exposure to them was more recent as I was delving into all things Rocketeer and discovered that Stevens did the cover to Airboy #5. Similar type content to the Rocketeer, pulp style aviation adventures and dove into that series too (which was so, so good and fun).

Scout was something similar. I'd always heard of it but never read it. I recently acquired as an afterthought the Eclipse trade that collects #8-14. Zot is the same way. Beforehand, I've read all of McCloud's texts on the comic art form, all brilliant and insightful. So I tend to think that his original series would exemplify that but upon first reading, I couldn't quite get into it. I need to try it again. I have the B & W collection that contains the end of the series and recently acquired the Eclipse trade that collects the first ten issues. I do love his recollections about the raw quality of this work and how he tried to evolve his craft beyond the more simplistic tropes of the medium.

So, I appreciate the focus on the wide range of genres that Eclipse had, something I was unaware of. (Though being an early anime fan, I did know about Mai and Kamui but never read them. My brother had all the Area 88 series of which I've read some, terrific drama and realism when it comes to the planes and hardware). So there's a number of titles now that I want to sample to see if I'd enjoy them.

Thanks for the terrific reviews.

|

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on May 15, 2017 22:49:22 GMT -5

Now, a preview of my next publisher. In 1984, two young artists who were struggling to get their work noticed sat around a table creating ideas for a comic book. One of them created a humorous sketch of a turtle, dressed like a ninja, in a spoof of Frank Miller's Daredevil stories and his new comic, Ronin. He showed it to his buddy and he then created his own turtle. Soon, they had four turtles and an idea. That idea led to a story and that story was self-published, with help from a tax refund and an uncle's loan. Those two artists were Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird; the book is Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.  Eastman and Laird put together a press kit and sent it out to newspapers and the wire services, which got enough attention to sell out of their initial print run. They reprinted and produced more comics. Soon, they had a cult hit and were mixing with Cerebus and had their stories reprinted by First Comics, in albums.   The comics were successful; but, what really set Eastman & Laird apart was how they pursued marketing their characters. They became involved with a medi licensing start-up, Surge, and were able to get an animated series greenlit, which helped secure a toy deal with Playmates. The end result was the biggest hit of the late 80s and early 90s. Eastman & Laird became millionaires. They did the usual things that you do when a truckload of money is dumped on your lawn. Eastman bought tons of original art and opened a comic art museum in Northampton, MA. He also bought one of the Batmobiles from Batman Returns, which he then brought around conventions. Eastman also found himself in new circles and met and married B-movie actress and model Julie Strain (since divorced). Eastman & Laird were big proponents of creator's rights and supporting self-publishers and alternative works. When Dave Sim got into a dispute with Diamond, over self distributing copies of the High Society phone book (which led Diamond to drop distribution of Michael Zuli's Puma Blues, from Sima's Aardvark-Vanaheim company), he and Eastman & Laird got a group of people together to draft a Creator's Bill of Rights. This was intended to be a shot across the bow for the independence of creators in the comic book world, taking back control of their work. Eastman & Laird took those ideas and acted on them in different ways. Laird set up the Xeric Foundation, in 1992, which provided grants to self-publishers, to allow them to fund publishing of their work (which continued until 2011). Eastman, after hearing many contemporaries lament having to work for the Big Two to pay the bills, when they wanted to do other work, decided to set up a company that could act as an umbrella for those creators, funding publishing and marketing, which would take the financial burden off the creator's shoulders. The end result of this idea was Tundra Publishing.  Tundra was launched in 1990 and it offered quality works, in high end packages. Eastman provided the funding for creators to go out and do what they wanted. It was a lofty idea that didn't quite work in the real world. Eastman didn't put many strings to the money he doled out and a lot of work didn't get turned in on time (or at all, in a couple of cases). In three years he pumped $14 million into Tundra; but couldn't keep it alive. However, in that 3 years, he published some amazing works and that is what I intend to look at next. So come on back as I look at Taboo, The Crow, From Hell, Big Numbers, Madman, The Brat Pack, Maximortal, Cages, and Understanding Comics. We will also look at the bizarre end of the company and the question of who bought whom, when Tundra merged with Kitchen Sink. Y'all come back now, ya' hear? |

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on May 18, 2017 22:28:19 GMT -5

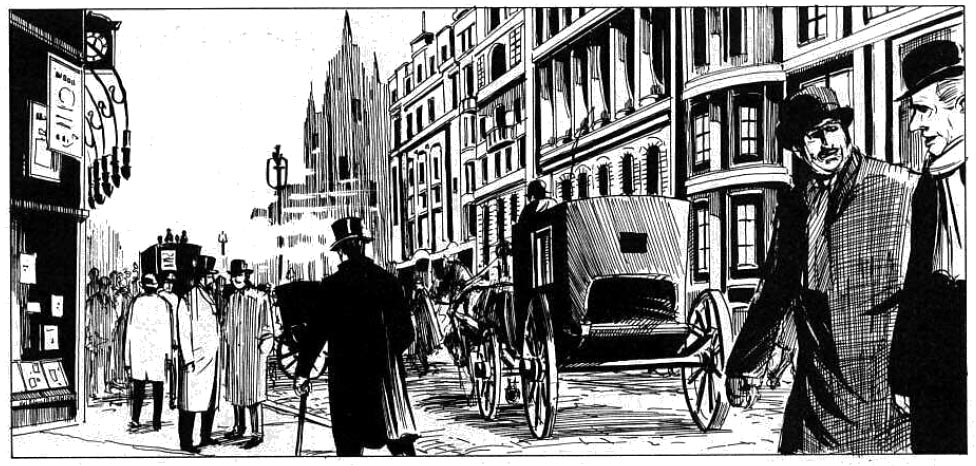

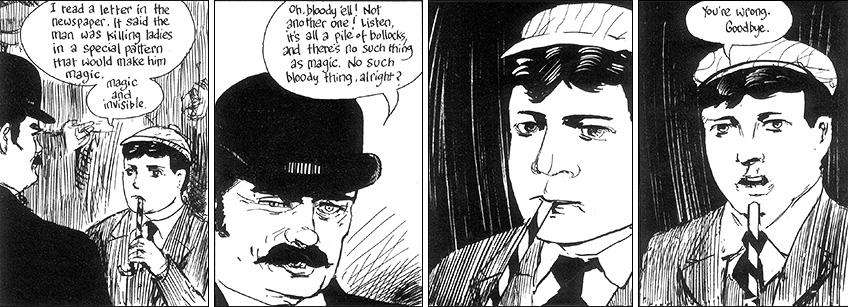

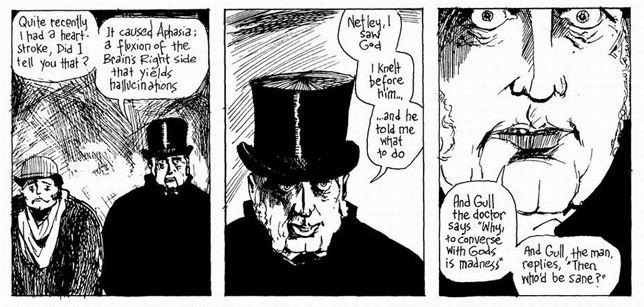

One of the people involved with Tundra was Steve Bissette. Bissette was involved both behind the scenes and with his own material. He had created his own anthology, Taboo, which was published by his own Spiderbaby Grafix. It was a horror anthology featuring material that the mainstream wouldn't touch.  Tundra helped publish and market the book, after it formed and Bissette took on his behind-the-scenes duties. I, however, never read it, as I am not a horror fan (too many nightmares as a kid, from even the tame stuff). However, there was a portion that did interest me, wit was where Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell's From Hell debuted.   I doubt I need to introduce this to many here, after a movie (not bad, not great) and closing in on 20 years in a collected format. It's Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell; what more could you want? Well, okay, here's the scoop. From Hell covers the Whitechapel Murders, carried out by one "Jack the Ripper." It was a sensationalistic murder case that had the country asir and had major political and social ramifications. Prostitutes were brutally murdered in the notorious Whitechapel district, which was a haven of vice and crime. As such, many in the upper classes considered it sordid but typical of those classes. As the victims were prostitutes, some felt they got what they deserved for conducting sinful business. However, for the working and underclasses, it was a terrifying nightmare, which led to vigilante groups, riots, and demands that the police do something. It has been the subject of numerous theories over the years, from the bizarre, to the politically-motivated. Moore and Campbell build their story around one of those theories; but, the book is more than a fictionalized account of events. They look into the social atmosphere of Victorian London, the coincidences, the public figures, and the harsh realities of the women who were murdered. The material is dense and the issues were filled with detailed notes, expanding on story material. We meet such figures as Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence, known as "Eddy" to his intimates, and the son of the Prince of Wales (the future Edward the VII), about whom rumors and scandals abounded. In the series, he is seen consorting with prostitutes, including Annie Crook, with whom he fathers a child. The murders are undertaken by Sir William Gull, the royal physician. Along the way, we meet figures including Joseph "John" Merrick (aka The Elephant Man), Buffalo Bill Cody and his Wild West Show (which toured England, but left before the murders began), Robert James Lees, an alleged psychic, and the women themselves: Mary Kelly, Polly Nichols, Anne Chapman, Catherine Eddowes, and Liz Stride. Detective Inspector Frederick Addeline is put on the case, though justice is not served to the public. Campbell's art is superb and the panels are packed with detail and the pages packed with panels, apart from major reveals. The writing is some of Moore's densest. Along with the depictions of life and politics in the era, as well as the Freemason conspiracy theories, we see William Gull is tortured by visions of the future, which also serve as an indictment of many elements of our modern world. The Victorian Era was a time of great change in the UK and Moore draws parallels with the then-impending Millennium. As history, Moore takes a lot of liberties, though he is fairly accurate in the social elements of the period, as seen from his own perspective. Eddie Campbell is the lesser-sung member of this team. He is a Scot, who lives in Australia, who produced his own work, as well as collaborating with Moore. His own material is a bit brighter than this subject, particularly his fictionalized, semi-autobiographical Alec, as well as his Bacchus stories (first published under the name Deadface), about the Greek god and associated figures. His style is deceptively simple, yet extremely expressive. His figures aren't filled with lines, yet they have weight. His sense of humor permeates his own work, though Moore is darker in this work. There are humorous moments, juts not many. Campbell invokes the spirit of the illustrations of the period...      The Taboo material was collected by Tundra and published in it's own book, then continued. However, this coincided with the financial fallout of Tundra's spending. the series would be continued at Kitchen Sink, after the merger, before being collected in 1999, as a complete work, under Campbell's Eddie Campbell Comics, then by Top Shelf. It is a regular feature in bookstore graphic novel sections, particularly after the release of the movie, with Johnny Depp, in 2001. The film is decidedly less than the original work, appearing to be more of a Cliffs Notes version of the story, with some mediocre acting. The tough, capable Abberline is depicted as an abuser of absinthe/opium cocktails. From Hell is an engrossing work, though it is one I only read twice; once in the serialized format, once in the collected. I have a low tolerance for that level of blood and horror, which overwhelms my interest in the social and historical. if you have similar tolerances, it's a tough work to get through. It is fascinating, but it is one that will likely have you wanting to read Pollyana afterward, just for a bit of optimism and sunshine. |

|

|

|

Post by mikelmidnight on May 19, 2017 11:36:13 GMT -5

From Hell is probably the closest I think comics have come to high literature.

One aside, about Campbell's art. I've always loved it, considered it suggestive in a way of using just the necessary lines to achieve close to realism. One odd caveat is that he can't draw superheroes at all! It's not simply a lack of necessary exagerration: every time he tries they look odd. He did a Batman Elseworlds where all of the characters are lively and quite expressive except for Bruce Wayne, who stands there as if he was carved from a block of wood or something

|

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on May 19, 2017 20:47:38 GMT -5

From Hell is probably the closest I think comics have come to high literature. One aside, about Campbell's art. I've always loved it, considered it suggestive in a way of using just the necessary lines to achieve close to realism. One odd caveat is that he can't draw superheroes at all! It's not simply a lack of necessary exagerration: every time he tries they look odd. He did a Batman Elseworlds where all of the characters are lively and quite expressive except for Bruce Wayne, who stands there as if he was carved from a block of wood or something And yet, he handles mythological characters well., in his own style (the Bacchus stories, especially Hermes vs The Eyeball Kid). Perhaps he saw Bruce as a block of wood that is just the facade, while Batman is the living person. Could have also have been editorial dictates at odds with what he wanted to do. Batman was guarded pretty well. Who knows? |

|

|

|

Post by mikelmidnight on May 20, 2017 11:33:25 GMT -5

Hermes vs/ the Eyeball Kid had an assist with the art. The one heroic-looking mythological character, Theseus, is probably the best he ever did with the heroic figure although his body looked stiff a lot of the time.

Batman looked awkward in the graphic novel too ... I had a fantasy that Campbell would have gotten someone to just help him out by doing tight pencils for all the Bruce/Batman figures for him to paint over ...

|

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on May 20, 2017 20:44:17 GMT -5

Several of the books published at Tundra started elsewhere; but, Tundra gave the creators funds to do them full time and complete them. One of these was James O'Barr's The Crow.           The Crow began life at Caliber, who published 4 issues, in black & white, after first debuting it in Caliber Presents #1. A story also appeared in A Caliber Christmas, and a 5th issue of the series was to be published and was previewed; but, not published at Caliber. Tundra collected the earlier material, with O'Barr expanding the material slightly. The best way to describe The Crow is with these words: Love, death, pain, grief, anger, vengeance. Tragedy dogs the work; in the inspiration, the telling of the story, and the adaptation into other media. James O'Barr was an orphan, who grew up in foster care. In an interview for The Crow movie dvd, he describes his early life as pure hell. The one bright thing was a woman he met and fell in love with, Beverly. She brought light into the darkness that was his life. Then she was torn from him when she was killed by a drunk driver. O'Barr was destroyed by grief. He enlisted in the Marines as a way to escape and cope and worked as an illustrator for manuals. In his spare time, he began work on The Crow. He poured his anger and grief into the book, via the surrogate lovers Eric and Shelly. The material sat on the shelf until O'Barr found a publisher who wanted to print it: the late Gary Reed, founder of Caliber Press. The work was unfinished, until Tundra stepped in and produced the definitive version. It would then be collected into a trade paperback, to coincide with the movie, after the merger of Tundra and Kitchen Sink. When Kitchen Sink was later sold to the media investment group, Disappearing, Inc, the Crow was one of the main attractions. The Crow tells the story of young lovers Eric and Shelly, who are starting out their humble lives, while deeply in love. On that fateful day, their car breaks down. They are assaulted by a gang of street thugs. Eric is beaten and shot in the head, though he is still alive, but paralyzed. He helplessly watches as Shelly is beaten, raped, and shot in the head. Shelly is DOA at the hospital and Eric dies on the operating table. He arises from the dead with the aid of a crow, a spirit guide. He then hunts down each member of the gang and brutally kills them, resting only when the job is complete. The book shifts back and forth between the softer scenes of young love, done in a wash style, with the attractive couple sharing their joy. It is all light and hope. That is juxtaposed with their murder and the vengeance path taken by Eric. That art is angry, with harsh lines and stark black & white (heavy on the black). The pages scream at you as Eric hunts and kills each member. The only other light is Sherri, a young girl neglected by her mother, who Eric meets and shares her torment. He gives her the engagement ring that he presented to Shelly, just before the attack. He is able to bring joy to Sherri, who never received a gift.      The Crow was optioned for a movie adaptation by Ed Pressman, who optioned several comic book properties in the 80s and 90s. Alex Proyas, who made a name for himself on the film Dark City, was to direct. Young actor Brandon Lee, son of martial arts legend and film star Bruce Lee, was to receive his major breakthrough role (after films like the Hong Kong Laser Mission and Legacy of Rage, as well as the tv movie Kung Fu: The Movie and action film Rapid Fire, with the late Powers Boothe) and immersed himself into the project. Filming was done in North Carolina, at the EUE Screen Gems Studio. The production was plagued by accidents, including a construction worker who impaled his hand on a screwdriver. Long nights of shooting affected cast and crew and Lee became a method actor, lying in beds of ice to feel what death was like. While filming his character's death scene, a .44 caliber handgun discharged a "dummy round," firing the projectile into Brandon Lee's abdomen. Dummy rounds are empty casings, with a projectile; but, no propellant powder or primer. The prop crew had created their own dummy rounds by emptying powder from live rounds; but, at least one round still had a primer and some powder, enough to fire the projectile. The round was fired during filming and the projectile was partially launched in the barrel of the revolver, where it remained lodged. A props assistant then reloaded the weapon with blank rounds, which contain a powder charge, but no projectile. When the blank round was fired, it launched the existing projectile into Brandon Lee's abdomen. He was rushed to a nearby hospital, but was pronounced dead, after attempts to revive him. Lawsuits followed and a settlement occurred, in which all footage was turned over to Lee's family to be destroyed, while the shooting was ruled an accident. An experienced firearms handler was not on set that day and the props assistant did not have proper training and experience in movie firearms handling, let alone basic firearms safety. The film was completed using body doubles and computer editing to match shots of Lee with the double. James O'Barr appears in the film as a looter, who steals a television set. The film was released to great critical praise, especially for Lee's performance. The soundtrack album was a major hit and it became one of the seminal films of the 90s. It also became a favorite of the Goth crowd and similar disaffected individuals, as the pain and anger of the story and the reality of both the comic and the film tragedies spoke to those in emotional turmoil. Many also found a beauty in the love of Eric and Shelly, finding the light within the darkness. A friend of mine named her son Draven, after the surname given to Eric in the film. Additional Crow comics, movies, and a tv series followed. None lived up to the original. The book is a tremendous personal statement from an artist coping with great loss and grief. There are few statements in comics that were more personal. |

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on May 24, 2017 15:24:25 GMT -5

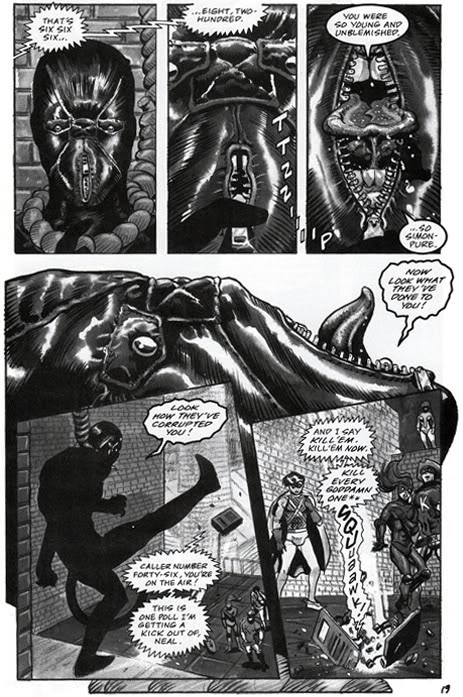

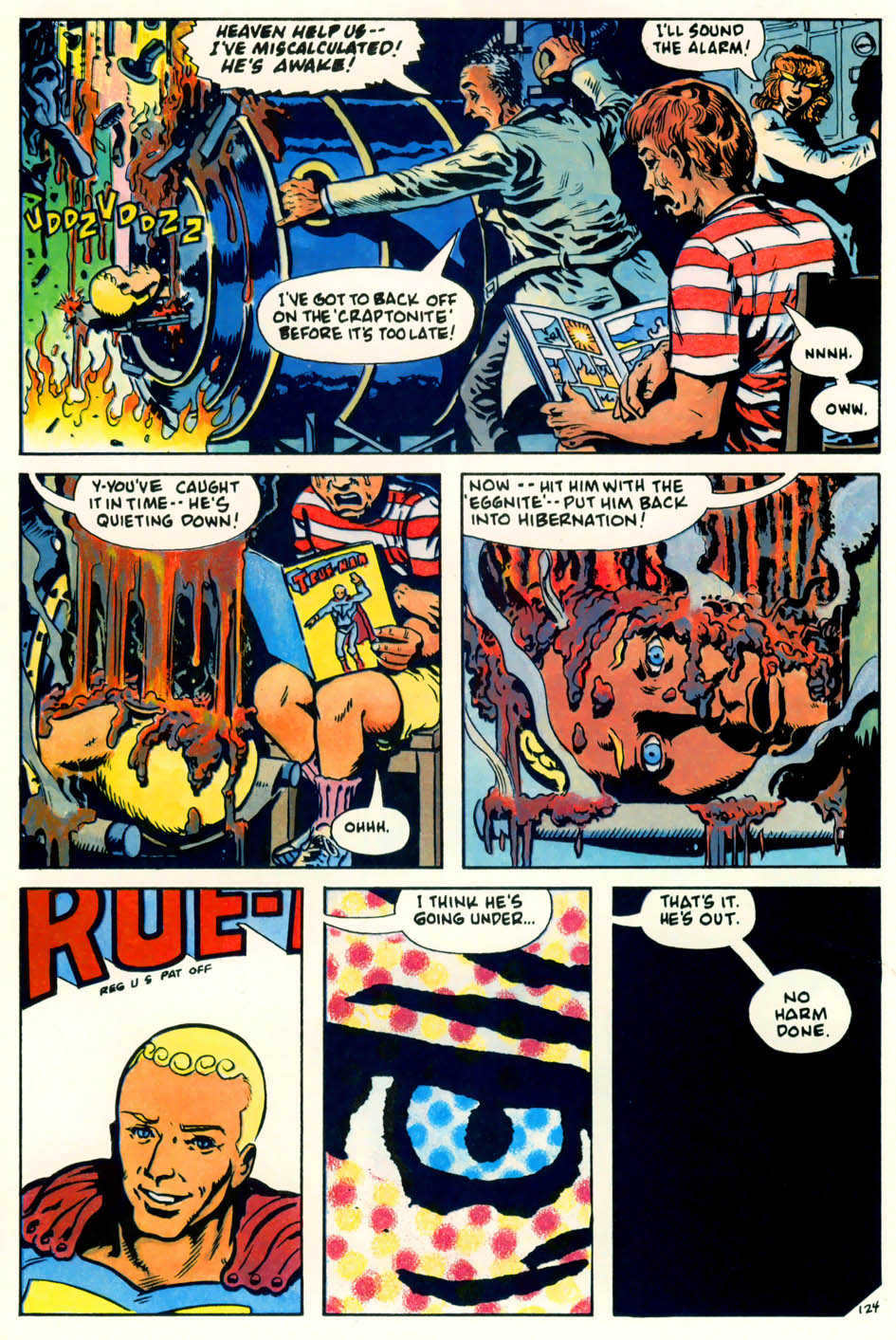

Next up, from Tundra, was another friend of Kevin Eastman, someone who had just done some work with the Turtles: Rick Veitch. Veitch had left DC over censorship of his Swamp Thing storyline, where the character had travelled back in time, meeting different DC historical characters, which culminates in meeting Jesus. DC had approved the storyline, then got cold feet and pulled it. Veitch walked out. When he left, he took with him an idea he had that was scheduled to be published at DC's Piranha Press imprint. It was a superhero deconstruction that honed the "edge" that Piranha Press sought into razor sharpness. Veitch already had experience with superhero deconstruction, with The One, published via Marvel's Epic imprint.  With The One, Rick Veitch picked up the superhero deconstruction banner from Alan Moore. With The Brat Pack, he ripped it to shreds!      The genesis of The Brat Pack occurred while Veitch was still working for DC. DC pulled a little stunt to help market a storyline called "A Death in the Family." You know the one, where everyone voted to kill off Jason Todd, who had been turned into an obnoxious little @#$%^& that everyone hated. So, no stacking the deck there. Well, some folks suddenly did a 180, after the decision was carried out. Me, I always felt that it was a foregone conclusion and the vote was manipulated by removing any redeeming qualities in Jason. The fact that one alternative page exists doesn't convince me that DC ever planned on keeping Jason alive (then). Anyway, having got their wish, some were horrified by the savage death. Some in the industry pointed fingers at the tastelessness of the stunt. More, however, looked at the sales and went right down the same dark and dismal path. Veitch decided to lampoon it, in the darkest way possible. Veitch came from an Underground sensibility, having created Two-Fisted Zombies with brother Tom, in 1972 (published by Last Gasp). He infused his work with that sensibility, which made him a more unique voice at a mainstream company, like DC. Piranha Press was an imprint created for edgier works and Veitch's idea fit in with that mindset. However, when the pulling of Swamp Thing #88 happened, Veitch walked and took his idea with him. Enter Kevin Eastman and Tundra. The Brat Pack starts out with shots of a decaying city, filled with pollution, trash, and crumbling buildings. The narration is a radio call-in show, where someone calls about "the children," meaning a group of superhero sidekicks, disparagingly known as The Brat Pack (after the name for the group of Young Hollywood actors that included Rob Lowe, Judd Nelson, Molly Ringwald and others). The DJ spews venom about them and encourages listeners to call with ideas about what to do with them. It gets more and more violent, to the distress of the original caller, who turns out to be supervillain Dr Blasphemy. Blasphemy rigs up a deathtrap which kills the youngsters, except Chippy the Wonder Boy. The heroes descend upon a priest, Father Dunn, to find new sidekicks. It seems that the church, St Bingham (aka St Bingo), is at the heart of this. New proteges are recruited, including a young altar boy, Cody (no relation) who desperately wants to be a hero. All of the kids come from homes of abuse and neglect. They are lost souls seeking purpose and acceptance. They fall prey to the worst collection of deviants, fascists, and parasites under the sun. Moon Mistress is a man-hating woman warrior, who indoctrinates a young girl into her society, as well as silicon implants, bulimia, and the hazards of unprotected sex. Judge Jury turns a troubled youth, with a fascination of Nazi regalia into a true fascist bully, attacking non-whites and doling out sadistic brutality, fueled by massive doses of anabolic steroids. King Rad was a weapons maker who turned into super liberal thrillseeker, and turns a poor young man into a boozing, drugged out skatepunk (with a hoverboard). The worst is the Midnight Mink, a pedophile who turns young Cody into his plaything, Chippy. The heroes are recognizable archetypes taken to Wertham extremes. Veitch makes them the embodiment of Wertham's criticism (fascists, gay pedophiles, man-haters, reckless role models) and then lets them get their clutches on these kids, and twist them into their own likeness. The priest is filled with self-loathing and suicidal thoughts, though he can't quite go through with it. We also see a shambolic figure, who turns out to be the previous Chippy, still alive, but practically a zombie. It turns out that all of the heroes owe their existence to True-Man, the Superman of this world. His blood mixed with the Midnight Mink, making him immortal, which he shared with Chippy. A reckoning is coming and it brings a climax to the story. Veitch's imagery is nightmarish and grotesque. These are not the clean lines of a Neal Adams; it is a heap of refuse and excrement that fills this dark world. The innocent kids are twisted into caricatures of the adults: Luna, Kid Vicious, Wild Boy, and Chippy. Luna has a pin-up body, and a face full of acne. She binges on potato chips and then purges. Wild Boy chugs beers and smokes crack, while wiping out on his board. Kid Vicious becomes more and more aggressive and anti-social and is even forced to attack a former friend. Chippy is seen shaving his legs on the cover of the first issue and his costume looks like something out of a porno. Doctor Blasphemy appears in a black bodysuit, covered in symbols used for profanity, in comics. His face is hidden by a leather domination hood, which he opens to reveal a literal acid-spewing tongue! The series had a brilliant marketing line:  A Dr. Blasphemy t-shirt, with the symbols on front and the tag-line on the back, was issued (and which tended to be about one-two sizes smaller than labelled). The series was then collected into a trade, published by Tundra, which included an altered ending. Many of the images from the series are very adult, but I'll try to provide a few examples of what is inside:   To superhero fans who saw it, it was either a smack in the face about how twisted heroes were in the extreme, or a darkly funny criticism of of mainstream heroes and sidekicks. It was Wertham on acid. It was also supposed to be the first of five parts of the King Hell Heroica. Part two soon followed.        If the Brat Pack seemed twisted, the Maximortal was pure scatalogical gross-out. The series tells the origin of True-Man, who resembles a certain blue and red-clad superhero of note. However, Veitch turns him into one twisted little alien. He pretty much kills the farmer who finds him on Earth, then forms a sort of parasitic bond. He is eventually evolved via the influence of comic books. Really, that is more of the minor point of the comic. The secondary feature is the real highpoint: a fictionalized retelling of how Siegal and Shuster were conned by DC. We see two young men conceive a True-Man comic and sell it to a conniving SOB, based loosely around Mort Weisinger (even though he didn't originally buy or edit the feature). We watch as the boys are pushed out and an empire built, while the sadistic little con artist creates a reign of terror. Veitch uses anecdote and urban legend to fill the story. The entire book has a sickening scatalogical element to it, based on some story about Weisinger that was probably gross (literally) exaggeration. Suffice to say, this isn't for the faint of heart and is even more Underground than The Brat Pack.    The Maximortal coincided with Tundra's implosion and ended up completed at Kitchen Sink, and was then collected. Veitch got sidetracked producing Roarin' Rick's Rarebit Dreams, his dream comics. He returned to the King Hell Heroica with new reprints and a Brat Pack/Maximortal special. Unfortunately, he didn't continue with the cycle, largely due to the nature of the industry and Diamond's increasingly restrictive practices, which squeezed small publishers out of the market. Veitch returned to costumed heroes with Alan Moore's ABC line, cocreating Greyshirt, an homage to Will Eisner's The Spirit. He also, previously, helped put together 1963, at Image (left unfinished), which was an homage to the early Marvel. The proceeds from that comic funded King Hell for a while, in the 90s, allowing Rarebit Dreams to be published. Fans of works like Preacher or The Boys may find much to their liking in the King Hell Heroica; fans of the Justice League and Superman may not, depending on their sense of humor and stomach for the grotesque. It ain't pretty; but, it is daring. |

|

|

|

Post by MDG on May 24, 2017 15:52:16 GMT -5

I was never a fan of Veitch (though his brother Tom wrote some very good undergrounds). I got through The One (barely) but had no desire at the time for the other stuff.

|

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on May 24, 2017 16:13:56 GMT -5

I was never a fan of Veitch (though his brother Tom wrote some very good undergrounds). I got through The One (barely) but had no desire at the time for the other stuff. The Brat Pack was more coherent than The One. Maximortal also makes more sense, though the Siegal & Shuster component is the only part that interested me. The rest of the book was just too weird and gross. I kept buying because of that story and despite the other stuff. The Brat Pack is actually a pretty decent piece, though pretty nasty. The One and The Maximortal do read more like an acid trip. |

|

|

|

Post by mikelmidnight on May 25, 2017 11:47:55 GMT -5

With The One, Rick Veitch picked up the superhero deconstruction banner from Alan Moore. I may be in a minority here, but I actually liked The One, in all its trippiness.  I never cared for The Brat Pack. I thought kid sidekicks weren't a rich enough fodder for this level of intense satire and criticism. All that said ... I adored the cover of the first issue, and it still makes me laugh. Maximortal ... as much as I love some of Veitch's work it just seemed too weird and gross to me and I steered clear. |

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on May 25, 2017 21:56:09 GMT -5

With The One, Rick Veitch picked up the superhero deconstruction banner from Alan Moore. I may be in a minority here, but I actually liked The One, in all its trippiness.  I never cared for The Brat Pack. I thought kid sidekicks weren't a rich enough fodder for this level of intense satire and criticism. All that said ... I adored the cover of the first issue, and it still makes me laugh. Maximortal ... as much as I love some of Veitch's work it just seemed too weird and gross to me and I steered clear. I read Brat Pack first, when it came out, then hunted down The One (got the whole thing at my LCS) and read it. I wanted to like it bit it was a little too trippy, for me. I kept hoping for more from The Maximortal; but, the Siegel/Shuster component was really the only part I liked. I loved 1963, for what it was and even read a big chunk of Rarebit Dreams, though it was extremely hit and miss for me. Greyshirt was pretty good. |

|

|

|

Post by hondobrode on May 26, 2017 20:31:41 GMT -5

The Veitch name on anything means I'm going to buy it.

At worst it's intersting.

Brat Prack and Maximortal were both disturbing, but very worthwhile.

I feel bad saying this, but I've never seen the Crow movie or read any of the comics. I will now thanks to the back story you put with it codystarbuck

|

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on May 27, 2017 11:15:58 GMT -5

The Veitch name on anything means I'm going to buy it. At worst it's intersting. Brat Prack and Maximortal were both disturbing, but very worthwhile. I feel bad saying this, but I've never seen the Crow movie or read any of the comics. I will now thanks to the back story you put with it codystarbuckI saw a poster, done by O'Barr, first and then an issue of the Caliber series. Then, the Tundra publication. I was excited for the movie, and it sounded really good in news pieces, during filming. Alex proyas had good press from Dark City, which was an excellent film, and Ed Pressman had a good track record as a produced of comic book film properties. Then, the tragedy struck. Brandon Lee was pretty good in Rapid Fire and I was looking forward to seeing him here, since it wasn't a martial arts film and it wasn't a pure action film. It was weird watching the movie, knowing what happened; yet, Lee is so good in it. This would have really kicked his career in high gear. he had a few weak spots; but, he did an excellent job. The murder scene, though, is spooky to watch. It's not the footage from the fatal shooting (that was turned over and destroyed); but, you know what happens and can't help seeing it in your head. At least, I did. The Crow DVD had an extra with an interview with James O'Barr, where he talks about the genesis of the project and the film. Don't know if it is on later releases or not. Never cared for the other films nor the tv series, though. I thought I heard there was reboot talk. Ugh! Try something new! How about a Strangers in Paradise movie? Heck, how about a Hepcats movie and get Martin Wagner to finish off his story? |

|

|

|

Post by codystarbuck on May 27, 2017 16:23:28 GMT -5

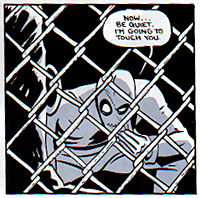

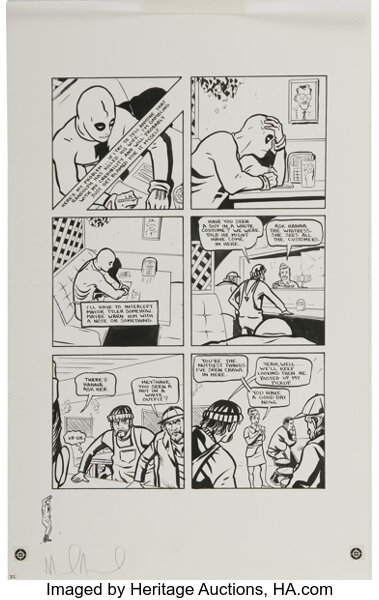

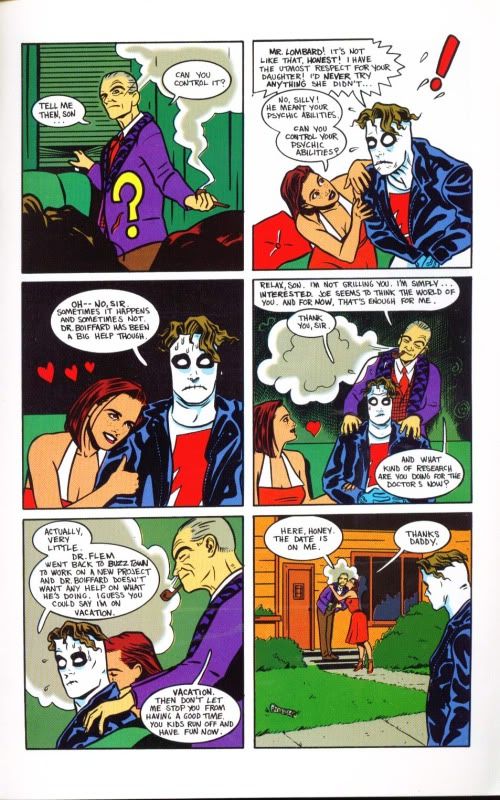

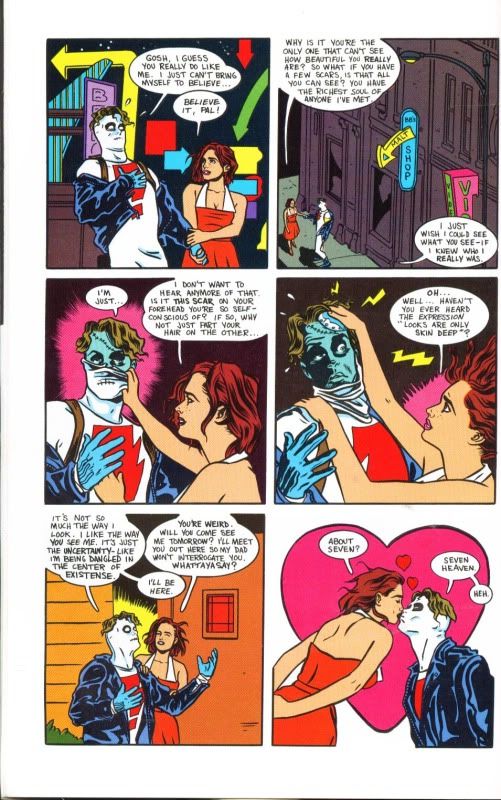

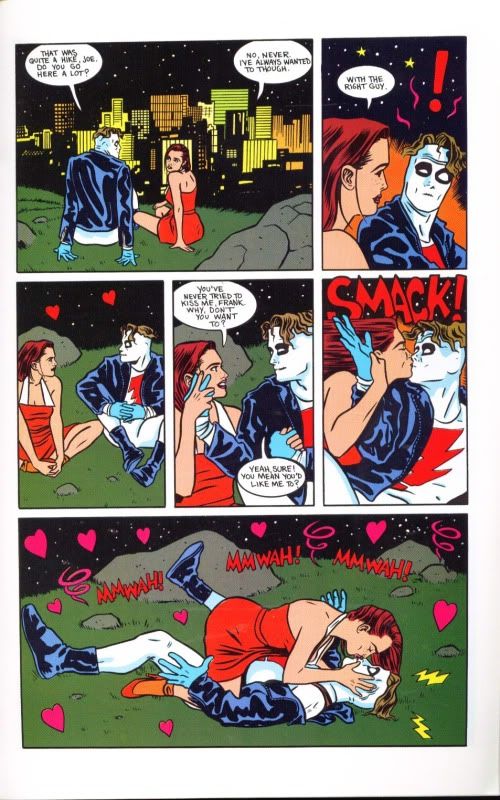

Now, if it seems like Tundra was filled with dark comics and dark humor, they helped throw a curve ball at the comic book world by publishing a young artist's groundbreaking work: Madman!       If you don't know Madman, you have missed all the fun! Like The Crow, Madman had his debut at Caliber, then got a leg up from Tundra. His first appearance was in Creatures of the Id:  However, it was that first Tundra mini-series that took the comic book world by storm and led to the follow-up, Madman Adventures. In his first full outing, we meet our masked hero, who seems a bit off. His face is covered by a full hood and he seems a little loopy. He acts like a superhero and uses a Duncan yo-yo as a weapon (hollowed out, with a lead center inserted!). He has lost his memory and is plagued by memories of a car accident. Some thugs are trying to kill him and steal the journals of a Dr Boifford. The masked figure stops them and rips out the eye of one, swallowing it to scare his partner into telling their boss, Monstadt, to back off and leave town. Well, the thug is a fibber and comes back with Monstadt. Fights ensue and we learn that this masked dude has Dr Boifford on ice, after Monstadt tried to have him run down. He is sent on an odyssey (The Oddity Odyssey, as it became known) to find Dr Gillespie Flem, Boifford's colleague. This takes Madman, as we know him, to a small town in what looks like the Northwest or similar wooded rural area. We finally meet Dr Flem, who is suffering from an infectious disease, inflicted by a clone of himself. There are fights with rednecks, monster clones, a damsel is rescued and we learn the truth of Madman. he was a man killed in an accident who was brought to Dr. Flem, who reanimated his corpse and named him after his heroes, Frank Sinatra and Albert Einstein: Frank Einstein. Freak learns rapidly; but, his monster appearance affects his self esteem and he rips out contacts that helped him learn. he also develops slight psychic and empathic powers, as well as fast reflexes. After saving Dr Flem and attaching his head (severed from his body to save it from the infection) to a clone body (which was cured of infectious cells, though it's head was cut off), he returns to Snap City to find his girl Joe (Josephine Lombard), kidnapped by Monstadt. He rescues her and destroys Monstadt.    The book is filled with absurd humor, much in the vein of The Flaming Carrot, and is filled with a gentle touch, plenty of bizarre imagery, and a lot of dynamicaction. Mike Allred burst upon the scene and people took notice. His style was different; not the over-rendered Image look, or the John Byrne or Frank Miller superhero look; it was at once typical of the independent crowd of the likes of the Hernandez Brothers or Dan Clowes, while infused with the dynamic action of Steve Ditko. It had a sense of humor that seemed a mix of Ernie Kovacs, Harvey Kurtzman, and Forrest Ackerman. It was unique and it was delightful. Allred soon became the hot darling of the indie scene. Oh, I almost forgot to mention; Allread included an animated sequence in each of the three issues, which could be seen by flipping the corners of the books pages. Now that was a gimmick to applaud, in an era of all too many gimmicks to abhor. Madman Adventures followed, with Frank and Joe rekindling their love life and Frank meeting Joe's father. He catches up with both Dr Boifford and Dr Flemm, does some time travelling, gets a few new outifts, and saves a stewardess from street beatniks (who would later go on to become The Atomics). It's all absurd, wondrously funny, and demonstrates how Allred was the perfect person to do Batman 66, as we see Frank scaling the wall of Joe's house, while she is leaning out the window, talking to him.    One of the elements that really works is the relationship between Frank and Joe. They look like a couple in love. Few modern comic artists handle this aspect well, as too many spent all of their time studying fight scenes and girlie magazines. Allred studied people and his characters look and move like real people (even the ones with heads grafted on bodies and weird deformities). Madman wen from cult hit to mainstream success, with further comics at Dark Horse, as well as crossovers with Bernie Mireault's The Jam, Mike Baron & Steve Rude's Nexus (a perfect match if ever there was one), and even the granddaddy of all, Superman. Through it all, the character stayed the same fun, loveable and absurd delight we had grown to love.      Madman also spawned some ultra-cool merchandise, including this awesome t-shirt, from Graphitti designs:  and a yo-yo!!!!  If that wasn't enough, not too long after Madman appeared at Tundra, word came out about a new cartoon from Stephen Spielberg's Amblin and Warner Bros, called Freakazoid.  Although the characters have different abilities and looks, the style and absurd humor is pretty darn similar. However, the truth of the matter is apparent in Bruce Timm's initial character design, which bore a striking resemblance to Madman, right down to the lightning bolt exclamation mark. The design was retooled before airing; but, many remarked about it in the fan press. Later, Allred spoke about it and stated that Bruce Timm told him that Madman had been a direct influence in the initial conceptualization, though the series went into a different direction when Timm bowed out and Tom Ruegger took over. The initial idea was an adventure show with comedic overtones, rather than an all-out comedy. One suspects that a lawyer at Amblin saw the Madman art and advised altering it. As it was, many who saw Madman first still felt that Freakazoid owed more than a little to Allred. Even so, Madman owed its life to many influences that came before it. |

|