Tintin in the Congo (French:

Tintin au Congo)

Original publication dates: May 1930 – June 1931

First collected edition: 1931 (redrawn colour edition published in 1946, with further changes made in 1975)

Author: Hergé

Tintin visits: Belgium (Brussels, Antwerp), Belgian Congo (Bomba, Matadi), Tenerife (Santa Cruz)

Overall rating:

Plot summary available here

Plot summary available here.

Publisher's synopsis:

The young reporter Tintin and his faithful dog Snowy set off on assignment to Africa. But a sinister stowaway follows their every move and seems set on ensuring they come to a sticky end. Tintin and Snowy encounter witch doctors, hostile tribesmen, crocodiles, boa constrictors and numerous other wild animals before solving the mystery and getting their story.Comments: For this second Tintin adventure, Hergé had initially planned to have his hero visit America – a country whose history and culture he adored. Unfortunately, his editor, Abbot Norbert Wallez, had other ideas and wanted Tintin to travel to the Belgian Congo in order to present a decidedly pro-colonial adventure to the young readers of

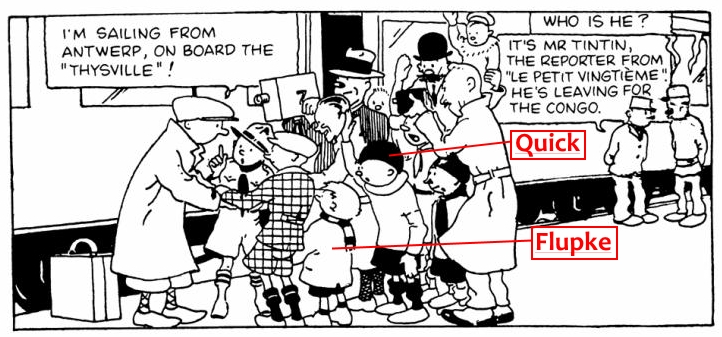

Le Petit Vingtième. So it is, then, that this second story opens with our hero and his dog, Snowy, standing on a Brussels train platform, bound for Antwerp, from where they will sail to Africa. In both the original black & white edition and the redrawn colour version from 1946, Hergé drops in a couple of sneaky cameos among the crowd of well-wishers on the platform: in the original strip, Quick & Flupke – two young troublemakers from another strip by Hergé, which ran alongside

Tintin in

Le Petit Vingtième – are visible among the crowd...

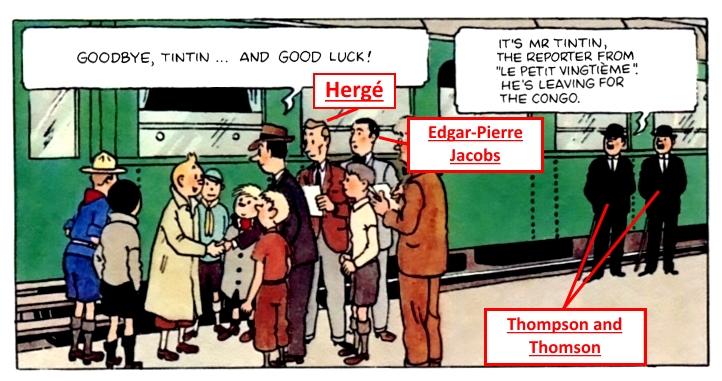

In the re-drawn 1946 version, Hergé himself appears as a journalist, along with his friend and

Blake & Mortimer author, Edgar-Pierre Jacobs. In addition, the Thom(p)son Twins are inserted into the background, retroactively making this their earliest appearance in the series (although their first proper appearance wasn't until 1934's

Cigars of the Pharaoh)...

It's clear early on in this story that Tintin and Snowy are already quite famous outside of Belgium. Indeed, upon arriving in Africa we see that the boy reporter's fame has even spread to the "Dark Continent", with crowds of cheering natives waiting to great them, as their ship docks at Matadi. Presumably this far reaching fame is a result of the pair having saved the capitals of Europe in

Land of the Soviets, but that is never actually stated.

While the art in the original version of this story is still pretty primitive compared to Hergé's later work, it definitely looks more like a Tintin book than

Land of the Soviets did. Tintin himself looks slimmer and more like he should, while Snowy's character is a little better defined too. We also have the very first appearance of the distinctive, spiralling motion lines that Hergé favoured and which would become such a signature part of the look of the series...

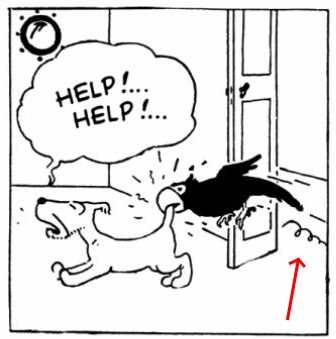

The humour too is a little sharper than in

Soviets and in some cases it actually raises a weak chortle...especially due to some of Snowy's antics. In particular, the faithful terrier's battle with an ill-tempered parrot early on in the story is very much in keeping with the cleverly executed psychical comedy that Hergé would master in later books.

Actually, Snowy has a fairly rough time of it in this adventure, what with getting savagely bitten by mosquitoes and forced overboard from a ship, where he almost drowns. In this latter scene, we see just how strong the bond between Tintin and his dog is, as the boy fearlessly dives into the ocean and risks the shark infested waters in order to save his canine companion. Then, later on in the story, Snowy boldly attacks a lion to save his master's life, showing that the selfless devotion between the pair goes both ways.

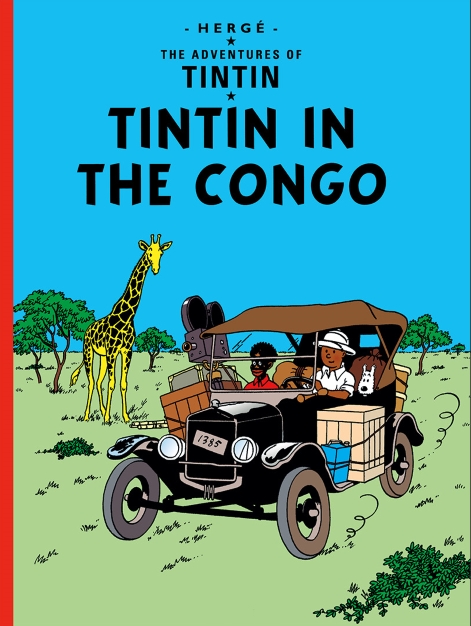

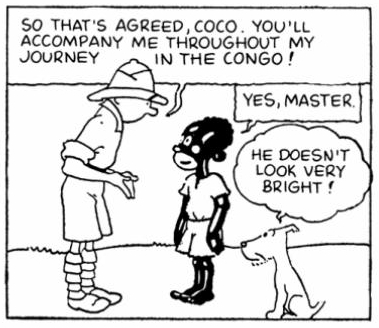

General improvements to the strip aside though, by far the most glaring problem with this book – especially to a modern audience – is its blatant racism. Just take a look at the cover image above of Tintin and his African guide, Coco (yes, that's right, Coco!), in a jeep. Now, that is most definitely

not a depiction of an African that you could get away with nowadays!

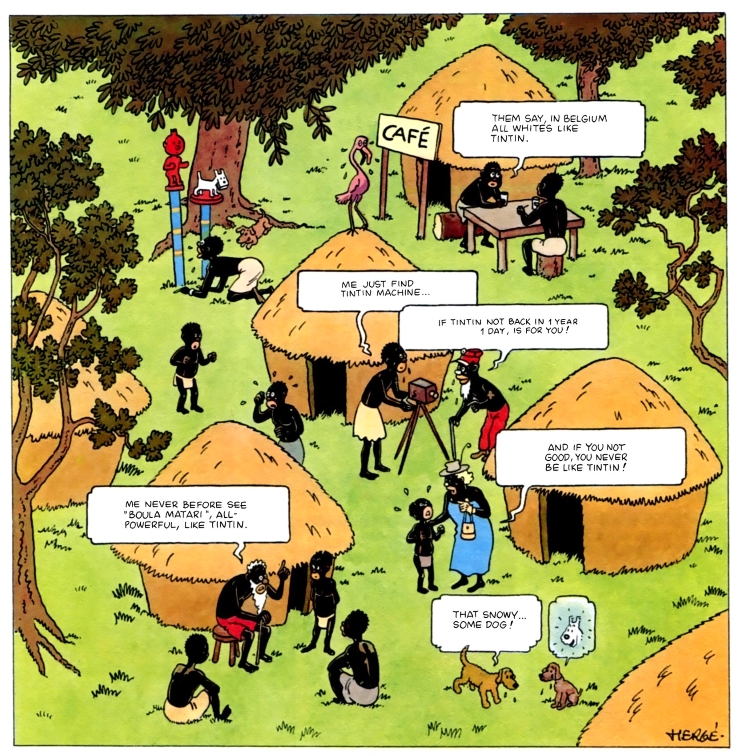

Things are much worse inside, however, where the natives are all depicted in a similarly appalling "rubber-lipped" and wide-eyed fashion. There's also something rather distasteful in the way in which the Congolese people seem to view Tintin and Snowy as almost god-like beings, going so far as to construct a totemic shrine to the pair in the final panel...

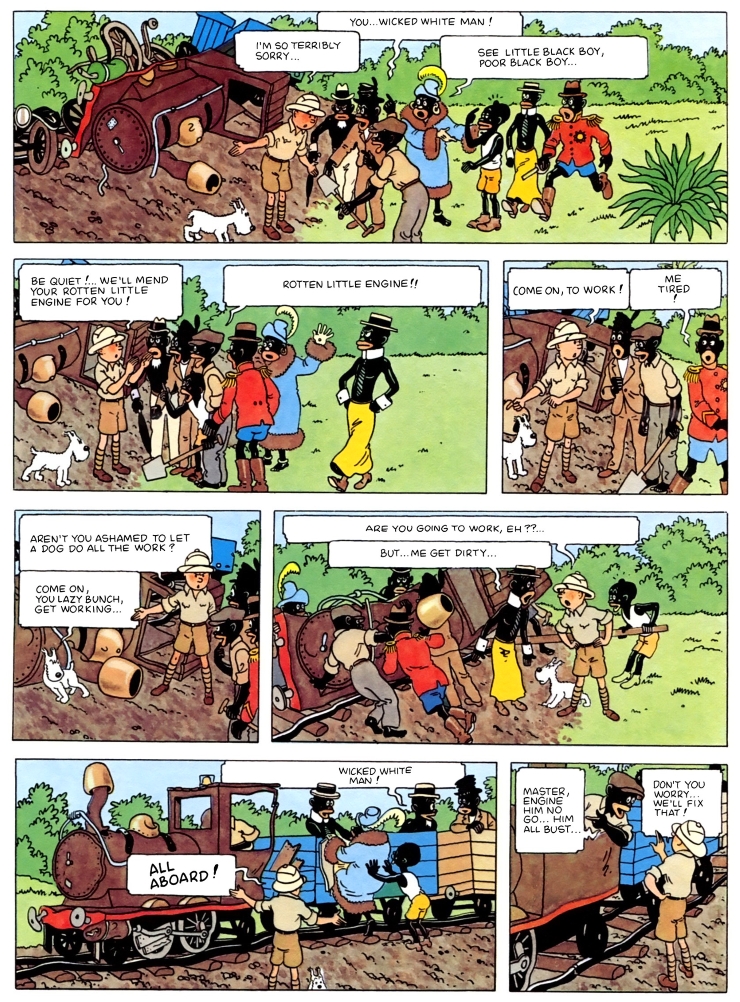

In addition, the Africans are universally portrayed as idle, unintelligent and superstitious, while their dialogue is spoken in a mildly offensive – although possibly accurate – Pidgin English dialect...

Snowy's remark of, "he doesn't look very bright", upon first meeting the Congolese guide, Coco, really sets the tone for the book...

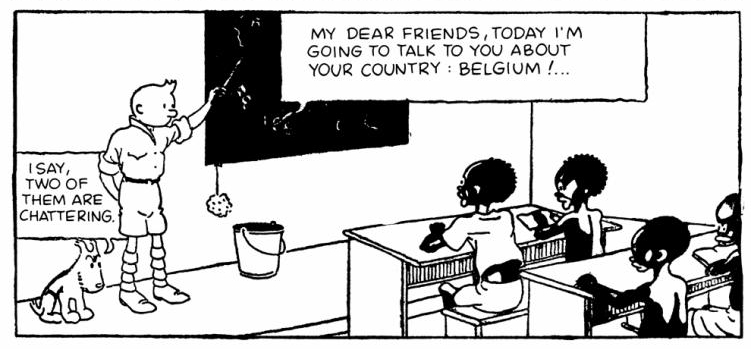

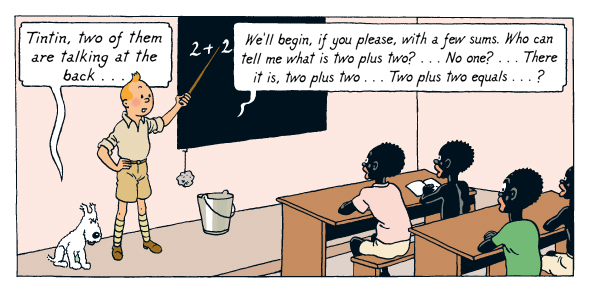

The pro-colonial propaganda that Wallez insisted upon including in this story is far from subtle, and arguably comes into sharpest relief during a scene in which Tintin instructs a classroom of native children in the superiority of their homeland of Belgium...

I should just note that Hergé did tone this colonial lecture down in the redrawn version of the story, turning it instead into a much more innocuous maths lesson...

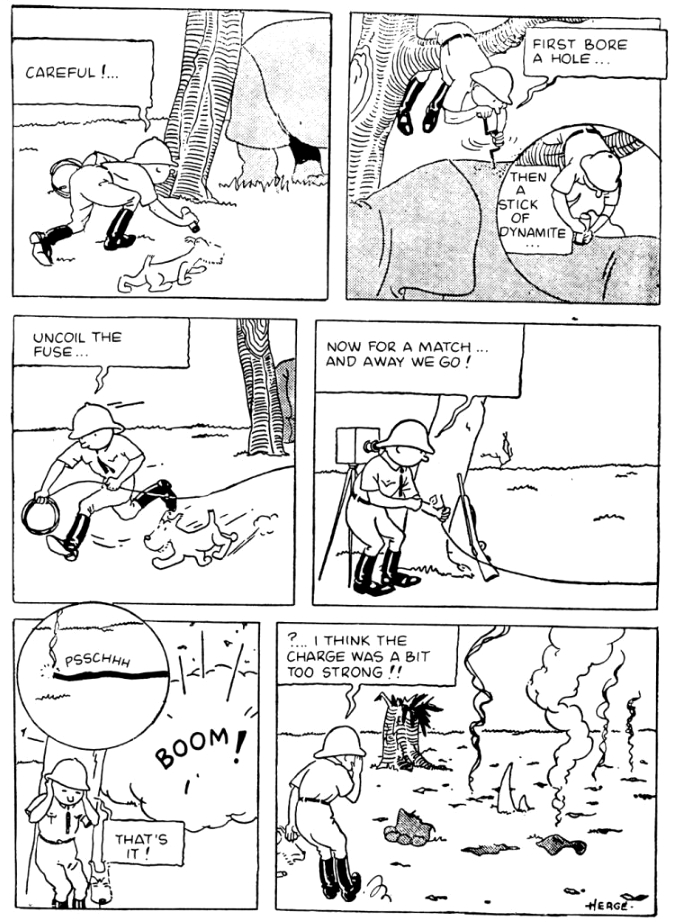

As if the racism and none-too-subtle pro-colonial subtext weren't enough, there's also the excessive animal cruelty to contend with!

Just to give you a flavour of the kind of gratuitous and bloodthirsty hunting shenanigans that you can expect in

Tintin in the Congo, at one point our hero drills a hole into the back of a live rhino, inserts a lit stick of dynamite, and runs for cover, as the poor creature is blown to tiny pieces. You know, just for fun and stuff.

In some post-1975 editions of the book, this sequence is changed so that the rhino escapes, but nevertheless, the overall body count in

Tintin in the Congo is absolutely horrific. During the course of the story, Tintin kills 15 antelope, 2 snakes, 1 rhino, 1 buffalo, 1 elephant (and he also takes the tusks!), he poisons a leopard, and shoots and skins a monkey, before wearing its hide. He also tortures a crocodile, while a missionary priest shoots three of the amphibious beasts, and Snowy tears the tail off of a lion, although he does so to protect Tintin. At one point in the 1946 edition, Snowy exclaims, "I can't stand scenes of carnage!" – yeah, I know how you feel, Snowy!!

Of course, you have to view Tintin's utter disregard for the African fauna within the context of its time: a period when big game hunting was a perfectly acceptable and even noble pass time for the upper classes. But to a modern audience, Tintin comes across as a bit of a d*ck, with his casual attitude towards the wildlife and his decidedly racist interactions with the native population.

Still, while it's true that

Tintin in the Congo is chock-full of decidedly un-PC stuff by today's standards, it should be noted that Hergé himself was deeply embarrassed by this story in later years. In his defence, I will say that his colonial and racist depictions of Africans were simply the product of a naive young artist who had read a lot of Belgian propaganda about the Congo, along with accounts of the region by African explorers, but who had never actually visited the country. As a result, there are a number of errors that creep into the story, such as when Hergé has Tintin fashion a catapult from a Brazilian rubber tree, which you simply wouldn't find growing at random in the Congolese bush. Likewise, there are no coconut trees in the Congo, as there are in this book.

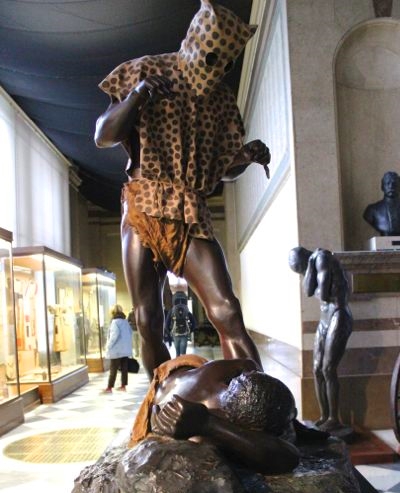

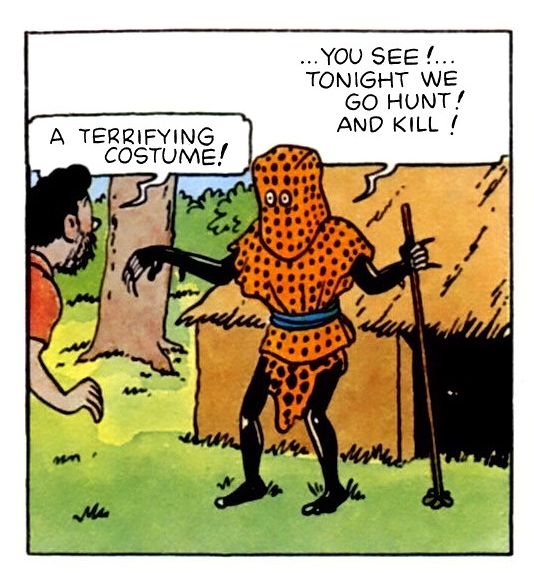

However, this is the story with which Hergé began to take steps towards the signature penchant for meticulous accuracy and authenticity that would be the hallmark of his later stories. For example, the "leopard-man" costume that the village Witch Doctor dons is a real artefact from an African cult that Hergé saw at the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervueren, Belgium, and which you can still see there today...

It's also worth noting that Hergé actually took a firm stand against hunting and poaching in later years, while actively attempting to counter "Yellow Peril" racism with his sympathetic and realistic portrayal of the Chinese in

The Blue Lotus. Nevertheless, to a modern reader, the racism and destruction of wildlife in

Tintin in the Congo is likely to leave a pretty bad taste in the mouth.

Focusing on the positive for a moment, one way in which

Congo scores over the previous Tintin adventure is that there is some semblance of a plot, with the presence of a recurring antagonist – a criminal who Snowy first discovers as a stowaway on the ship that takes them to Africa – who turns out to be one of Al Capone's henchmen. It seems that Capone is concerned that Tintin will disrupt his control of diamond production in the Congo and has sent some of his men to finish off the pesky reporter. At the close of the story, Tintin is rescued from a buffalo stampede by two Belgian pilots in an aeroplane, and whisked off back to Brussels for an important new case, which leads right into the third book,

Tintin in America. Still, while there is some vague plot line, for the most part this story just meanders along in a similarly episodic and unstructured way as

Tintin in the Land of the Soviets did – mostly consisting of a series of chase sequences or escapes, strung together by a flimsy plot.

Summing up, I personally find the colonial attitudes, blatant racism, and bloodthirsty slaying of wildlife in this story to be much more objectionable than the political propaganda of

Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. Yes, these story elements are a product of their time and the racism is fairly casual, rather than a harsher, more vindictive or hateful form. But, of course, it is still racism nonetheless and is liable to cause great offence to a modern audience. The animal cruelty and racist content were toned down slightly in the redrawn colour version of the story which is commonly available these days, but nevertheless,

Tintin in the Congo is hardly what you'd call a politically correct, PETA approved adventure yarn.

Still, at the time of its original publication, the story was another tremendous success and once again ensured that there would be follow-up adventures for the boy reporter. Putting the inherently offensive nature of much of this book aside for a moment, I tend to rank it just above

Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, simply because it has more plot to it and because it's a slightly more skillfully constructed adventure than its predecessor.

This is an unusually dated Tintin adventure and I would definitely caution newcomers against reading this book as their first exposure to the series. They would be much better off starting with

Tintin in America or any of the books that came after that.