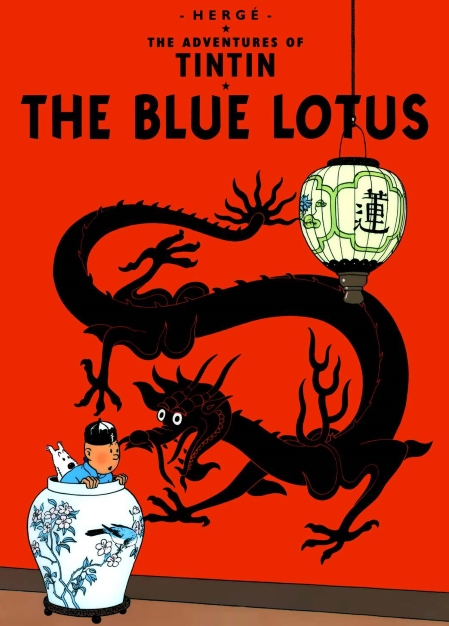

The Blue Lotus (French:

Le Lotus bleu)

Original publication dates: August 1934 – October 1935

First collected edition: 1936 (partially redrawn colour edition published in 1946)

Author: Hergé

Tintin visits: India (Gaipajama), China (Shanghai, Hukow)

Overall rating:

Plot summary available here

Plot summary available here.

Publisher's synopsis:

The story is set in 1931. At that time Japanese troops were occupying parts of the Chinese mainland, and Shanghai, the great seaport at the mouth of the Yangtze Kiang (River), possessed an International Settlement, a trading base in China for Western nations, administered by the British and Americans. Hergé based his narrative freely upon the events of the time, including the blowing-up of the South Manchurian railway, which led to further incursions by Japan into China and ultimately to Japan's resignation from the League of Nations in 1933.Comments: Originally published between August 1934 and October 1935, in the pages of the Belgian children's newspaper supplement,

Le Petit Vingtième,

The Blue Lotus represented a creative leap forward for Hergé. For one thing, the author finally did away with the random, serialised plotting of earlier Tintin adventures and instead focused on devising a carefully structured plot. For another, Hergé fully embraced the quest for realism, which he'd made steps towards in

Tintin in America and

Cigars of the Pharaoh, while simultaneously attempting to portray the culture and people of China as accurately as possible. The final creative breakthrough was with his development of the

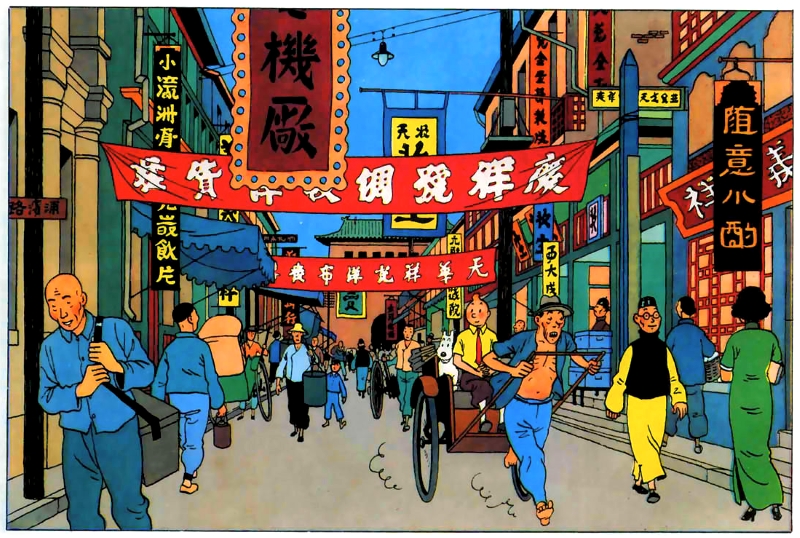

ligne claire ("clear line") style of drawing, which placed emphasis on cinematic realism in the settings and backgrounds, contrasted with slightly cartoonish characters in the foreground, and drawn using strong, clear lines of the same width, with no hatching or cross-hatching.

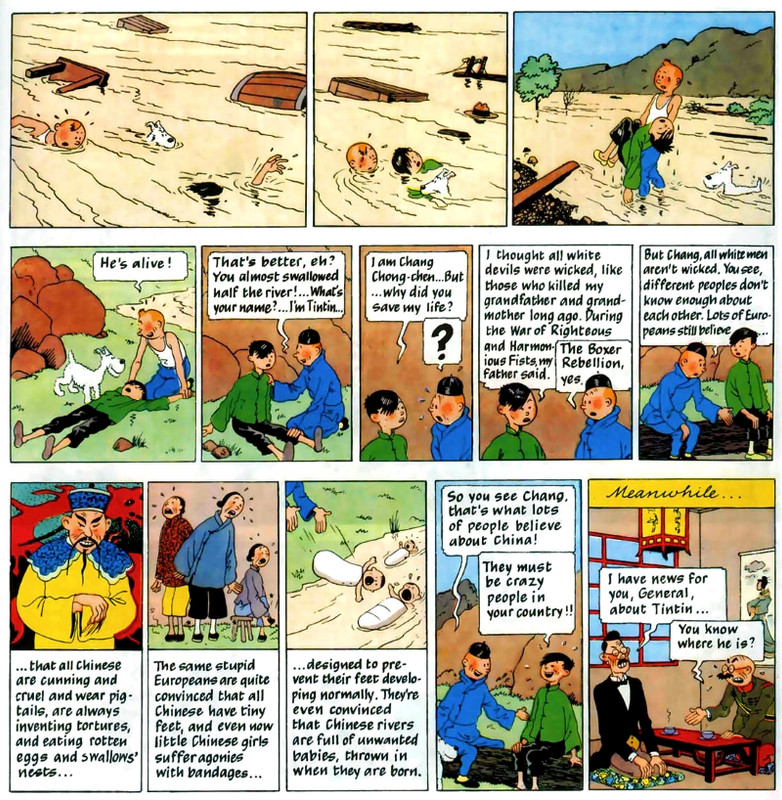

Hergé's sympathetic and realistic portrayal of the Chinese in

The Blue Lotus was largely the result of a new friendship that the author had struck up with a Chinese sculpture student named Chang Chongren. From the long discussions that this friendship fostered, Hergé learned about the true nature of Chinese culture, history, and philosophy, and how far away it was from the clichéd prejudices held by himself and many other Europeans. In return for opening his eyes to the "real" China, Chang was immortalised in the book as Chang Chong-chen, a special young friend for Tintin...

In the above scene, Hergé goes out of his way to dispel then-prevalent myths among Europeans about the Chinese people. That such a sensitive and sympathetic portrayal of an exotic, far away culture should come only three short years after the author's, frankly, appallingly intolerant depictions of the Congolese in

Tintin in the Congo, serves to illustrate the rapidity with which Hergé was evolving as a writer.

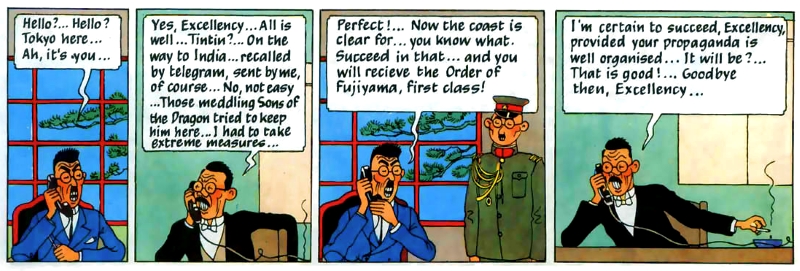

Still, it's not all tolerance and sensitivity in this book: while the Chinese may be treated with respect, the Japanese are all portrayed as evil, incompetent idiots and, in contrast to the depictions of the Chinese, are all drawn in a pretty racially insensitive way – all slit-eyes and buckteeth...

I find it interesting that the author should, on the one hand, attempt to counter widespread and long-held prejudices against East Asians and yet still pander to the worst excesses of "Yellow Peril" caricature in his depictions of the Japanese. It's certainly obvious just from the way in which Hergé draws the Japanese who he thinks the bad guys in this part of the world are! I should also note that the author is rather uncomplimentary about the British presence in China too.

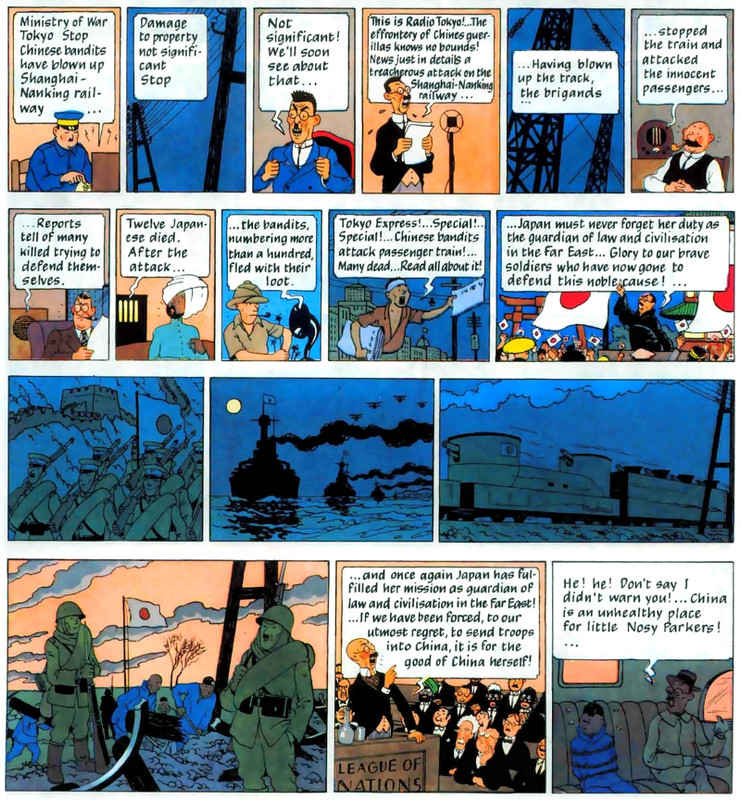

In addition, Hergé is critical of Japan's rampant imperialism and expansionist ambitions. The author even goes so far as to take the real world event known as the "Mukden Incident" – in which the Japanese military staged an attack on the South Manchurian railway in 1931, as a pretext for an invasion of north-eastern China – and incorporates it into his story. For the purposes of

The Blue Lotus, the attack is moved south to Shanghai, but nonetheless, the resultant invasion and Japanese empire building is depicted by Hergé with some knife-sharp satire...

Such biting political commentary was unusual – if not altogether unprecedented – for a children's comic of the time and there were apparently angry letters sent to

Le Petit Vingtième from parents complaining that such content was wildly out of place in the supplement. Children, however, loved the story, enjoying the high adventure, daring-do and many plot twists, without necessarily fully grasping its political subtext.

Something else that was, presumably, quite unusual in a children's comic is the large amount of drug references present in

The Blue Lotus. Tintin is still on the trail of the opium smugglers that he encountered in

Cigars of the Pharaoh, of course, but the Blue Lotus itself turns out to be an opium den. In one scene, we even get to see our hero partaking in an opium pipe...

To be fair, there's no smoke coming from the boy reporter's pipe, so we should probably give him the benefit of the doubt – and anyway, he would probably want to keep his wits about him, since he's in the establishment attempting to glean information about the drug smugglers. But still, we definitely see other people smoking opium or laying zonked out due to its effects.

The Blue Lotus picks up where the previous book left off, with Tintin still staying at the Maharajah of Gaipajama's palace. The young reporter also has a new hobby in the shape of shortwave radio...

Of course, the shortwave radio is really just a device for Tintin to obtain clues about the opium smuggling ring that he uncovered in

Cigars of the Pharaoh, thus setting him off on the trail to China.

A page or two later, we get an amusing scene in which a local, fortune-telling fakir clues the reader into the fact that the head of the smuggling ring is still at large (that being Roberto Rastapopoulos, of course). Tintin, however, is still none the wiser when he meets the Hollywood film tycoon later on in the book. It's not until the dramatic conclusion of the story that Tintin finally realises what the reader has suspected for quite some time, that Rastapopoulos is behind everything. Happily, the arch-villain is apprehended by Tintin and incarcerated, but he will be back to menace our hero later on in the series.

On a related point, I love the way that Hergé has Tintin duck into a cinema in order to escape his Japanese pursuers, only to find himself watching the very scene of Rastapopoulos's latest Cosmos Pictures' film that the boy reporter interrupted in

Cigars. That's a neat piece of continuity.

The humour found in

The Blue Lotus is funnier than that present in the previous story, but this is still a much more serious book than, say,

Tintin in America. There's a "weight" to this story and even a vague sense of angst pervading it, which would render the belly laughs that we got in

America decidedly out of place. Still, that's not to say that

The Blue Lotus is dour, by any means! Tintin's canine sidekick, Snowy, certainly provides some chuckles, being at his cynical and sarcastic best right from the opening page. The Thom(p)son Twins return in this adventure too, bringing their amusingly well intentioned, but hopelessly inept buffoonery to proceedings...

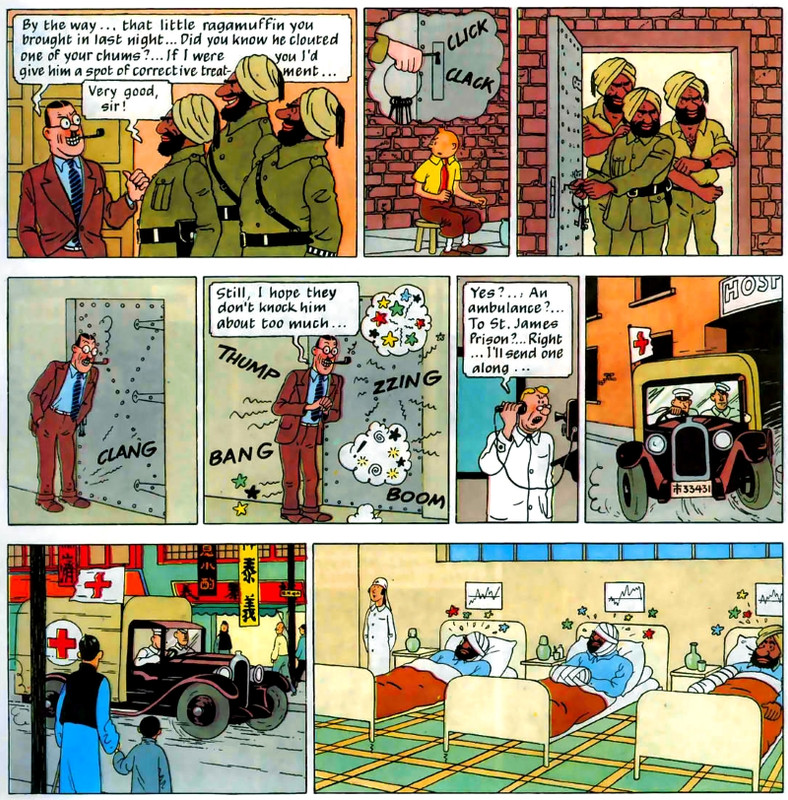

Tintin himself provides some humour too. I particularly enjoy the scene in which three huge Sikh soldiers enter our hero's prison cell, in order to rough him up a bit, with the reader being led to believe that the boy reporter has gotten a real pasting, right up until the "punchline" of the final panel....

Overall, the artwork found in this book is excellent, with some beautifully detailed backgrounds and brilliantly executed action.

The Blue Lotus really represents a new peak for Hergé's artistic skills. The narrative is well served by the art and flows very naturally from page to page, with impeccable pacing and clarity; you never have to look twice at a panel in order to discern exactly what is going on. It's a testament to Hergé's draughtsmanship in the original 1936 version of the adventure that, when

The Blue Lotus was re-published in 1946 – in the standard 62-page colour format – very little of the art was actually changed. The "touching up" was reserved for some embellishments to the backgrounds and a few other minor alterations.

There are lots of examples that I could include to illustrate just how gorgeous the artwork is, but I'll limit myself to showing just a couple of the most impressive panels...

I also want to note that all of the Chinese writing on the street signs in

The Blue Lotus is proper Chinese, diligently written out by Hergé's friend, Chang. If you're fluent in Mandarin, the street signs apparently offer their own jokes or even meta-commentary on what is happening in a particular scene. I know, for example, that the green poster in panel 1 of page 9 (see below) humorously reads, "No posting bills."

If you're interested in deciphering all of the Chinese street signs, a quick Google shows me that the Tintin fan website tintinologist.org has a full breakdown/translation of them

here.

Despite the excellence of this book, I do have a couple of minor complaints or criticisms. Hergé introduces so many Japanese military characters that I find it difficult to keep track of them all and things kinda become confusing at points. Also, it seems a little too contrived to me that Mitsuhirato would kidnap the "madness doctor", Professor Fang Hsi-ying, just to prevent Tintin from having him cure all those who have been poisoned with the Rajaijah Juice.

However, those trifling complaints aside,

The Blue Lotus is a fantastic comic that marks the moment where the series really hits its stride and The Adventures of Tintin kick into high gear. The narrative is pretty fast paced, carrying the reader along on a ripping adventure, with plenty of action, surprising plot twists and some pointed political commentary. The overall structure of the book is much more satisfying than previous adventures too and it's also the most dense Tintin book that we've seen so far, with the panels tightly packed together and lots happening on a page.

In addition, Hergé finally perfects the character of Tintin himself, with our hero being much more of a detective than a reporter, while also acting as a champion of the oppressed and downtrodden. As a result, this is really the first time in the series that we see the Tintin that we know and love. Simply put,

The Blue Lotus is Hergé's first unequivocal masterpiece.