Post by Roquefort Raider on Aug 4, 2020 10:12:23 GMT -5

Les mangeurs d'hommes de Zamboula (The Man-Eaters from Zamboula, alternatively titled Shadows in Zamboula).

Adapted from R. E. Howard's short story by Gess.

An excerpt can be found here (in French).

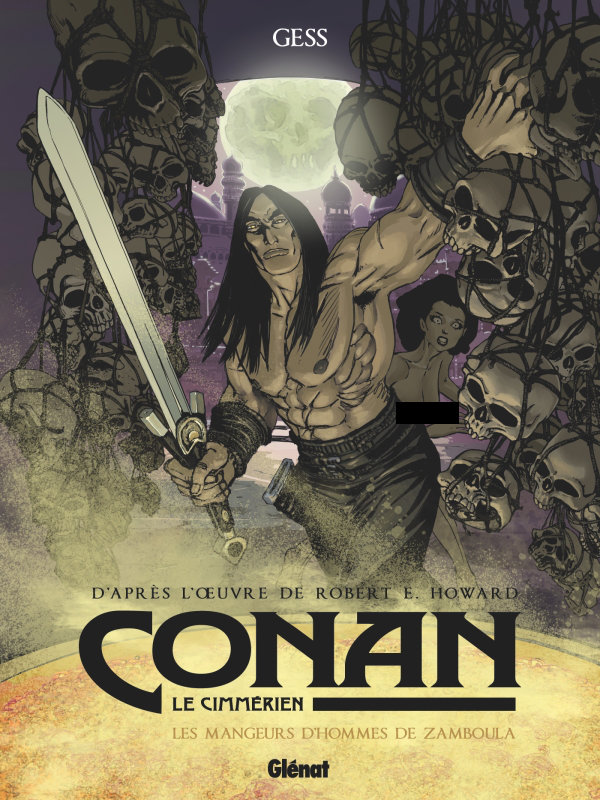

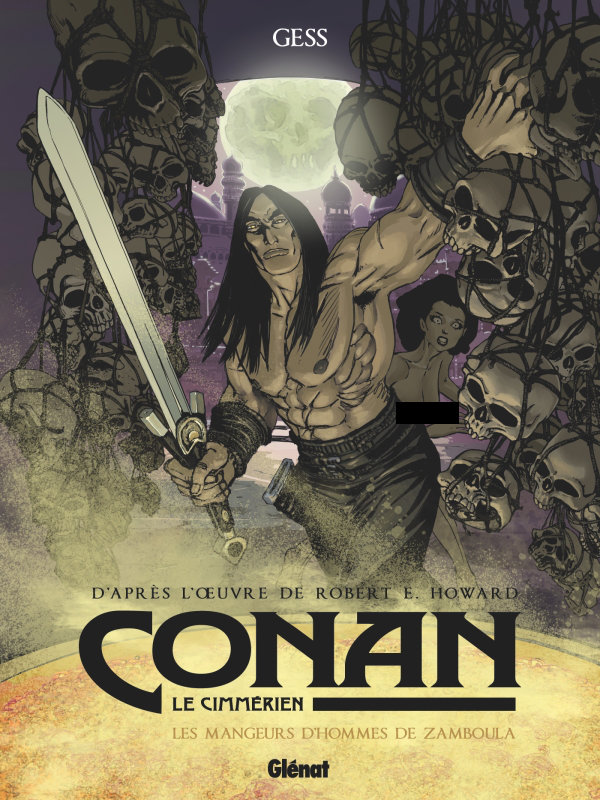

Gess is the pen name of Stéphane Girard, a seasoned pro who shows great enthusiasm throughout this book. His adaptation is the truest to the original material we've seen to date in this series; his linework is rich and dynamic, and his colour work is brilliant. I'll admit I was a bit scared when looking at the sort-of cartoonish cover, but the man's work won me over right on page 1!

On several occasions, while reading this book, I thought "hey, this bit of dialogue is great! Gess sure knows how to capture Howard's style!" only to discover, while checking the original, that the artist had simply been true to the text. Those lines had simply not been included in the Marvel comics adaptation, and since I re-read the comic more often than the prose tale, I had forgotten them. Props to Gess for restoring them!

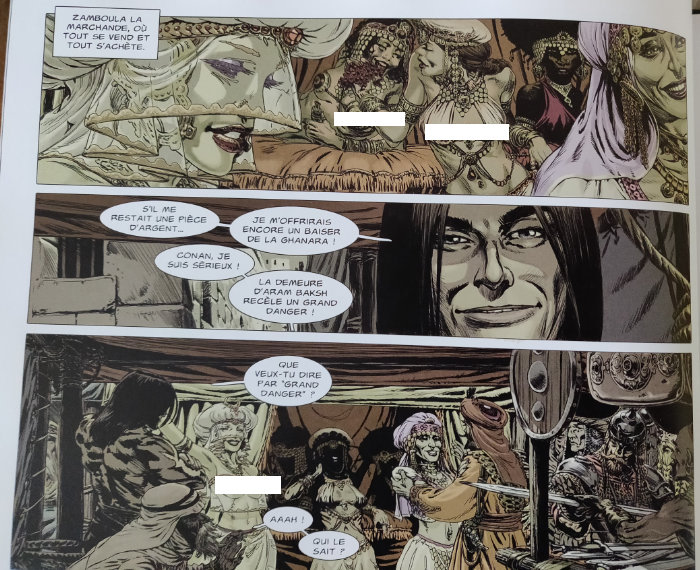

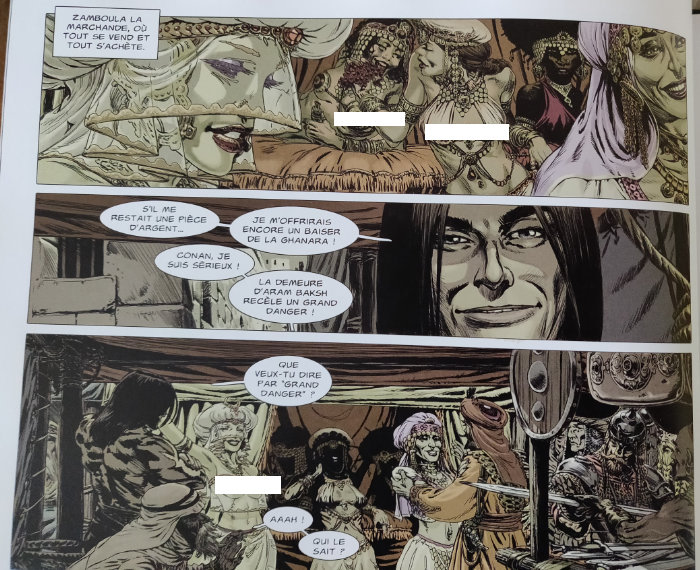

What's more, what little he does add is also perfect. At the start of the story, Conan and an old Zuagir are chewing the fat in Zamboula's marketplace: Conan complains about having next to no coin (as in the original) and adds that if he had more silver, he'd buy a few more kisses from a certain Ghanaran girl selling her charms right around the corner. This line not only shows that Conan is quite the bawdy fellow (which will be important later in the tale) but also that he's not all about Gigantic Despair... there's also the Gigantic Mirth!

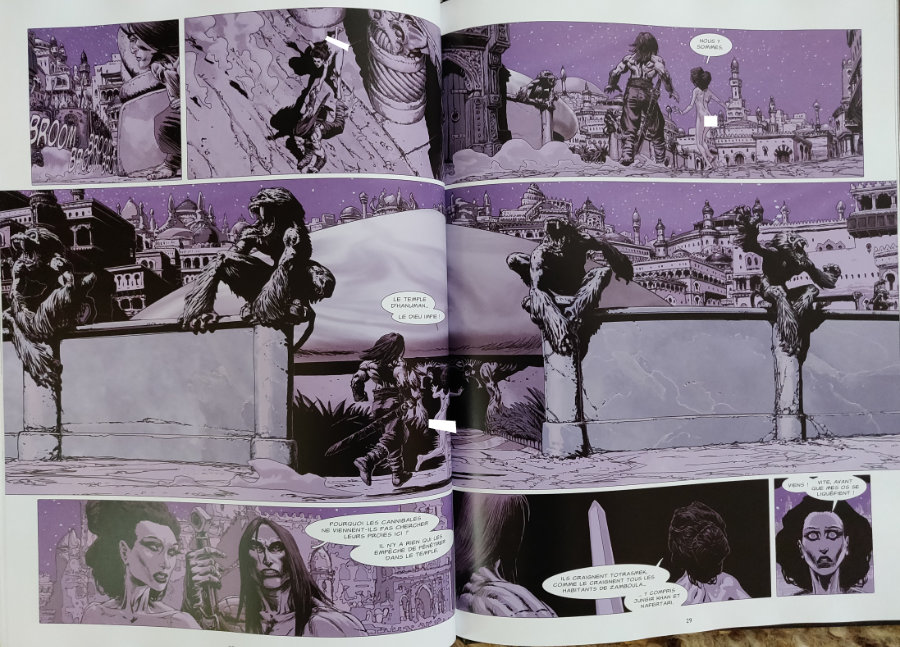

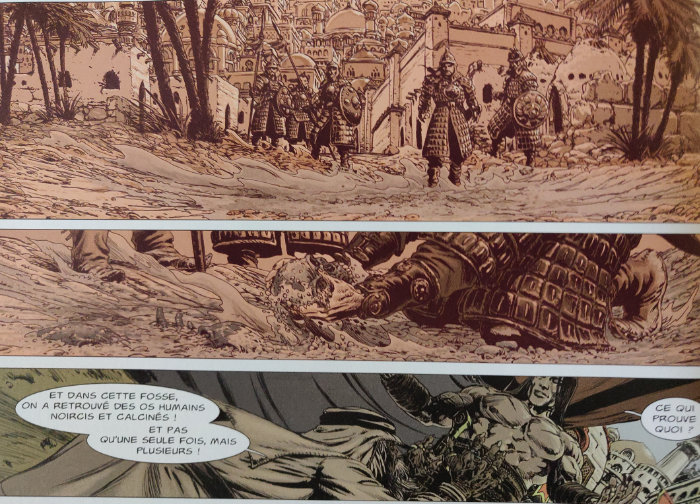

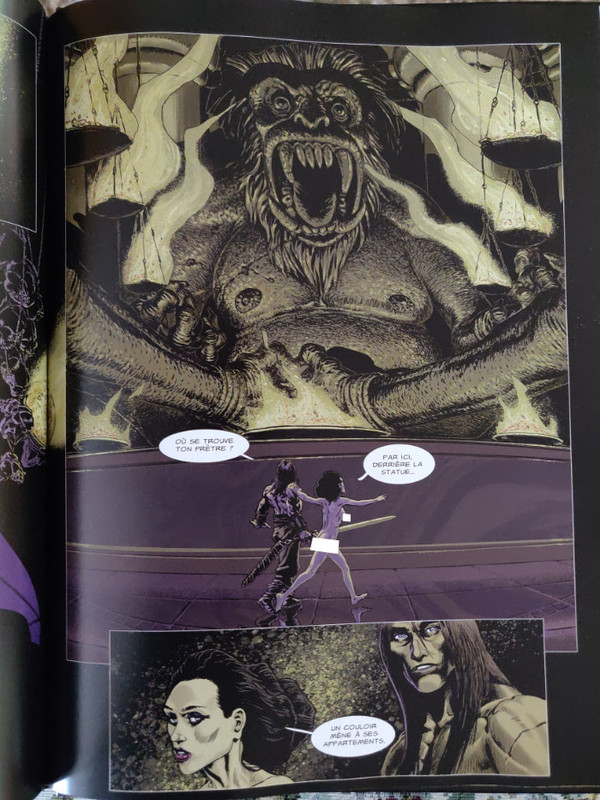

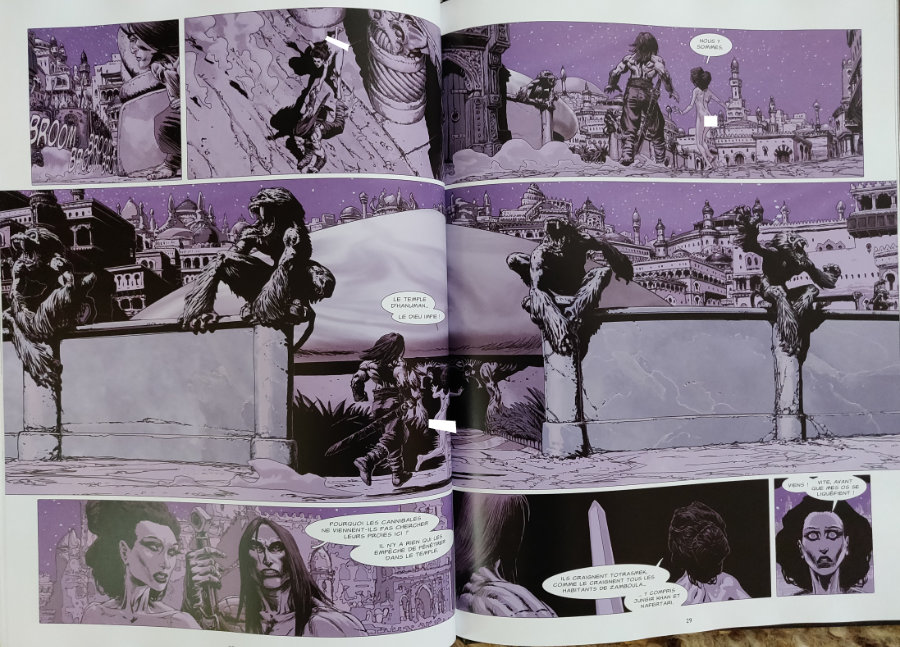

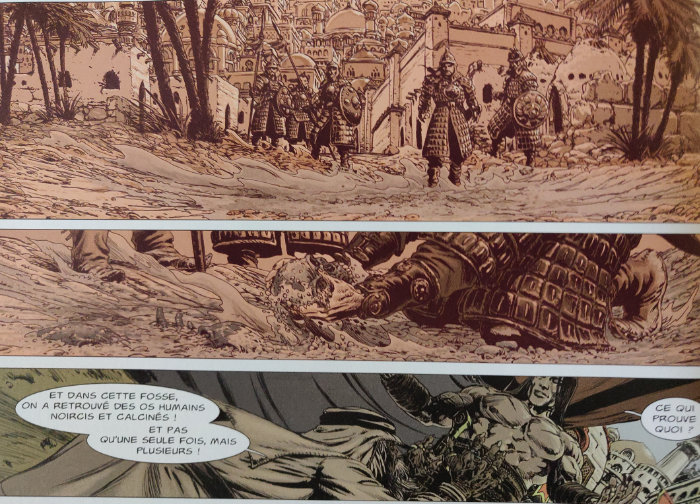

The art is extremely detailed, and each image allows us to take a look at what life must be like in Zamboula: alleys filled with unique characters, shops with exotic goods, soldiers in practical but impressive-looking gear, majestic temples and the like... All that we rightfully expect from an Age Undreamed Of, and that Gess delivers aplenty.

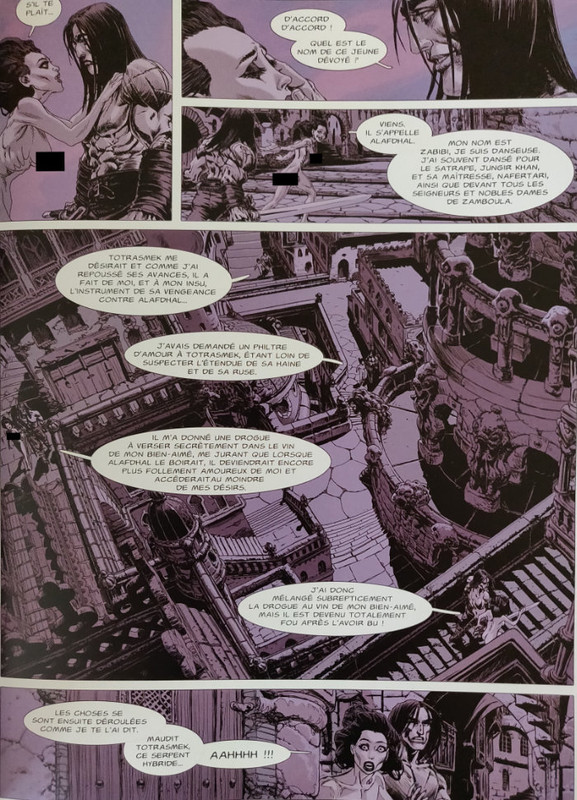

Warning to American readers: as in the original story, the main character Zabibi is naked throughout the tale. And not the comic-book kind of nudity where a silk loincloth and conveniently placed tresses manage to hide everything: we're talking full frontal French nudity (zose naughty, naughty Frenchmen! )

)

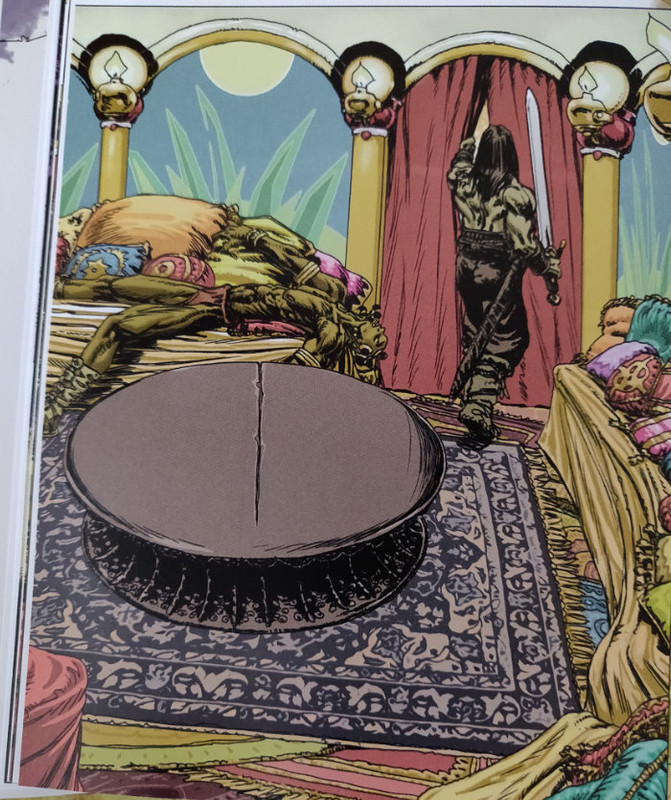

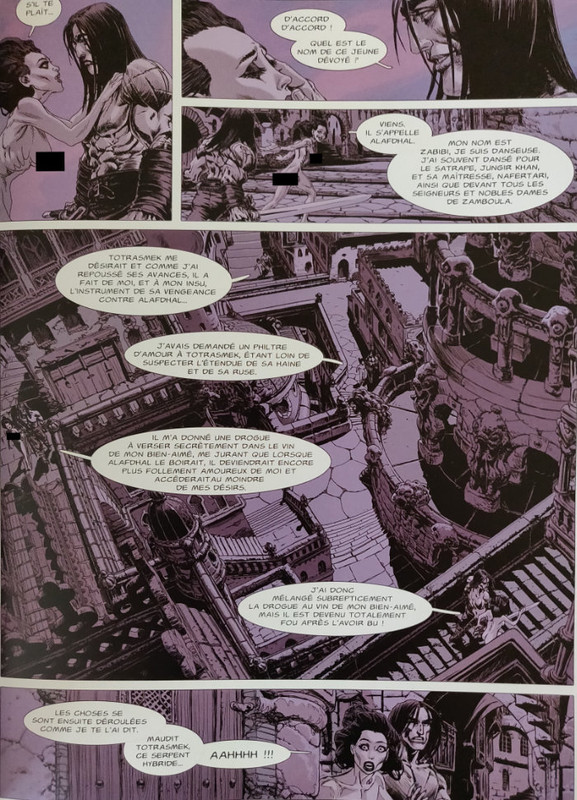

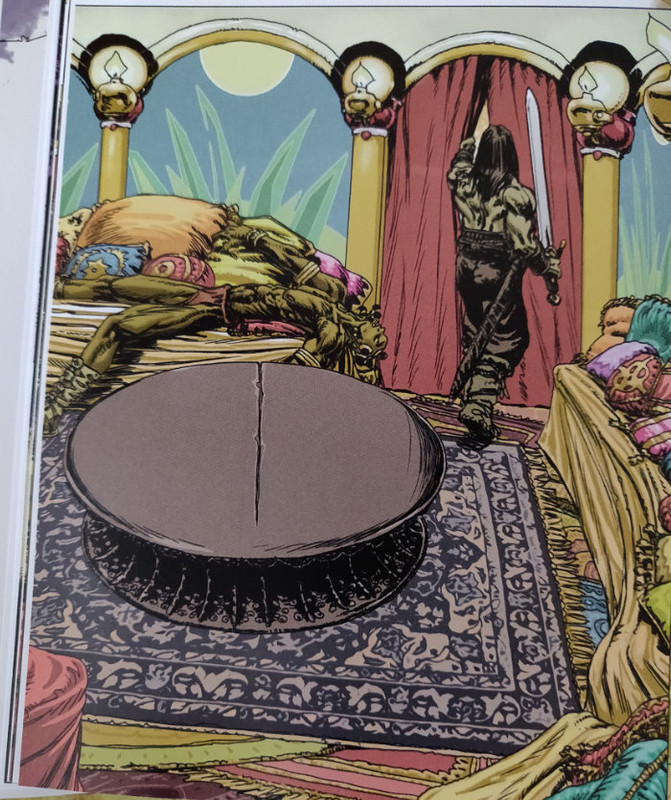

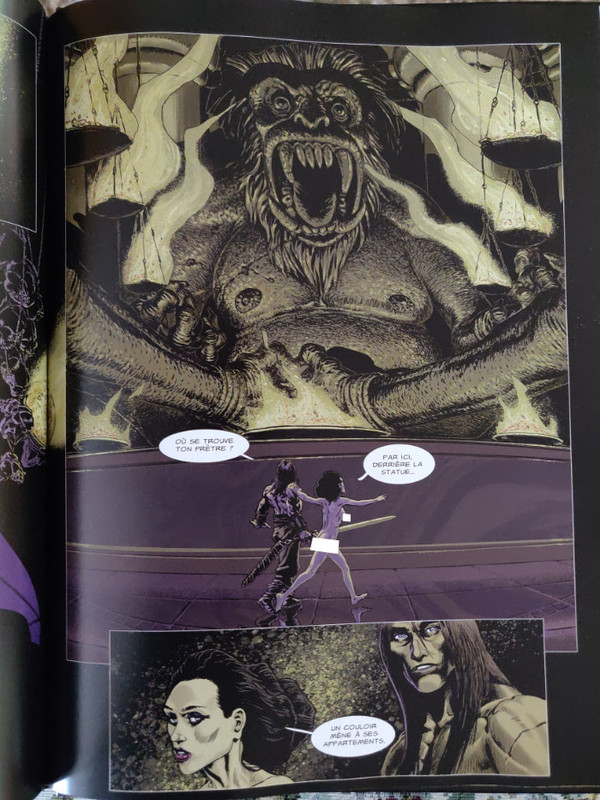

The colours contribute beautifully to the mood of the story, whether it's the ocres and browns of the desert, the muted purple of the night or the pink of the approaching dawn. Only in the temple of Hanuman do we see the many-coloured opulence of rich tapestries and carpets. It's all lovely to look at.

Zabibi's nakedness is however not used as a titillating storytelling device (as it doubtless was in Howard's prose story): in Gess's hands, Zabibi's nakedness first emphasizes her vulnerability (as someone running naked through the streets while being chased by cannibals is probably feeling very vulnerable), then emphasizes her steely resolve (since once out of danger, she doesn't care about being naked). What convinces me that Gess knows full well what he's doing is that while Zabibi's certainly not hard on the eye, she's also not drawn like a comic-book cheesecake model. She looks like an actual person.

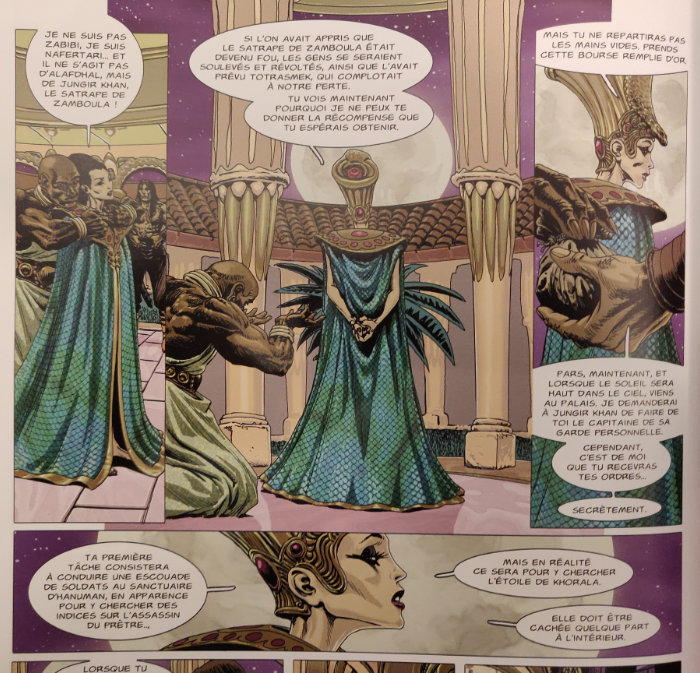

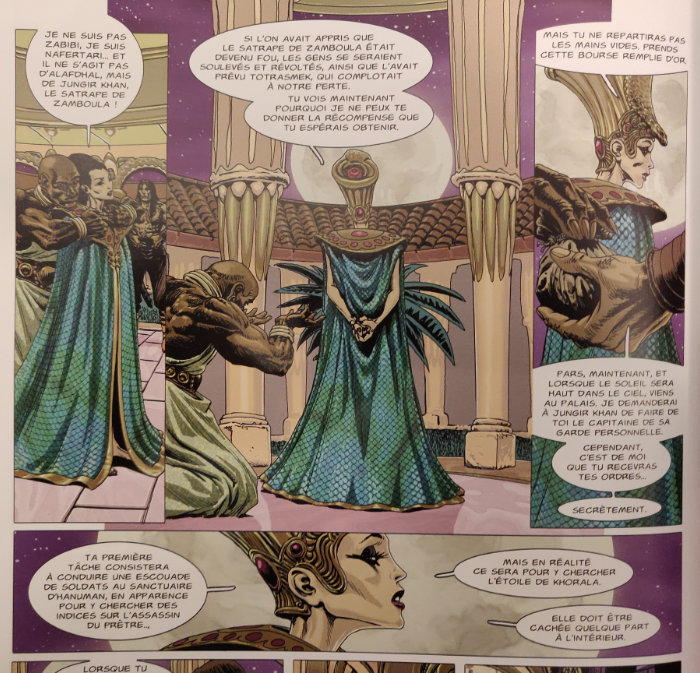

At the end of the story, Gess also adds a little personal touch that makes use of Zabibi's unclad state: when she is revealed to be Nafertari, the actual ruler of the city, one of her slaves is finally getting her dressed in clothes fitting her position. This helps raise a wall between her and the lustful Conan, who had been promised something else than just gold for his services, and the transition from scared and naked dancer to authoritative ruler is graphically much more impressive when presented that way than in the original story (and than in the SSoC adaptation), in which the lady just tells Conan who she is.

I am pretty sure that Gess will be the target of outraged comments for not updating The Man-Eaters of Zamboula to suit modern sensibilities. The sexism and racism of the original story are still there, and I, for one, couldn't be happier for this steadfastness in adapting an old pulp story; as long as no one is making excuses for racist or sexist characters, I don't mind them being racist or sexist. The Hyborian Age was simply not an enlightened one, and it would be as wrong to pretend otherwise as to pretend that the lions in Tarzan are vegetarian.

Like the preceding books, this one has a text piece by Patrice Louinet, on the genesis of Howard's story. It is clearly not one of Louinet's favourites, and he sees it as purely commercial (which, in all honesty, it pretty much is). Following the tepid reception of Howard's brilliant Beyond the Black River (which didn't warrant a cover illustration) and the outright rejection of The Black Stranger, Howard resorted to a tried and true formula: a simple plot in an exotic land, with a naked girl in a kinky scene sure to get the glorious Margaret Brundage treatment. Howard might have wanted to experiment more with his prose, but he knew which buttons to push to get Farnsworth Wright to accept a tale and give it the Weird Tales cover spot.

The book also has a few pin-ups that aren't bad, but not that special either.

Altogether, because of the excellent artwork and especially the very faithful adaptation of the prose story, this would be my second-favourite book in this series. (The Frost Giant's Daughter is probably unbeatable at this point!)

Adapted from R. E. Howard's short story by Gess.

An excerpt can be found here (in French).

Gess is the pen name of Stéphane Girard, a seasoned pro who shows great enthusiasm throughout this book. His adaptation is the truest to the original material we've seen to date in this series; his linework is rich and dynamic, and his colour work is brilliant. I'll admit I was a bit scared when looking at the sort-of cartoonish cover, but the man's work won me over right on page 1!

On several occasions, while reading this book, I thought "hey, this bit of dialogue is great! Gess sure knows how to capture Howard's style!" only to discover, while checking the original, that the artist had simply been true to the text. Those lines had simply not been included in the Marvel comics adaptation, and since I re-read the comic more often than the prose tale, I had forgotten them. Props to Gess for restoring them!

What's more, what little he does add is also perfect. At the start of the story, Conan and an old Zuagir are chewing the fat in Zamboula's marketplace: Conan complains about having next to no coin (as in the original) and adds that if he had more silver, he'd buy a few more kisses from a certain Ghanaran girl selling her charms right around the corner. This line not only shows that Conan is quite the bawdy fellow (which will be important later in the tale) but also that he's not all about Gigantic Despair... there's also the Gigantic Mirth!

The art is extremely detailed, and each image allows us to take a look at what life must be like in Zamboula: alleys filled with unique characters, shops with exotic goods, soldiers in practical but impressive-looking gear, majestic temples and the like... All that we rightfully expect from an Age Undreamed Of, and that Gess delivers aplenty.

Warning to American readers: as in the original story, the main character Zabibi is naked throughout the tale. And not the comic-book kind of nudity where a silk loincloth and conveniently placed tresses manage to hide everything: we're talking full frontal French nudity (zose naughty, naughty Frenchmen!

)

)

The colours contribute beautifully to the mood of the story, whether it's the ocres and browns of the desert, the muted purple of the night or the pink of the approaching dawn. Only in the temple of Hanuman do we see the many-coloured opulence of rich tapestries and carpets. It's all lovely to look at.

Zabibi's nakedness is however not used as a titillating storytelling device (as it doubtless was in Howard's prose story): in Gess's hands, Zabibi's nakedness first emphasizes her vulnerability (as someone running naked through the streets while being chased by cannibals is probably feeling very vulnerable), then emphasizes her steely resolve (since once out of danger, she doesn't care about being naked). What convinces me that Gess knows full well what he's doing is that while Zabibi's certainly not hard on the eye, she's also not drawn like a comic-book cheesecake model. She looks like an actual person.

At the end of the story, Gess also adds a little personal touch that makes use of Zabibi's unclad state: when she is revealed to be Nafertari, the actual ruler of the city, one of her slaves is finally getting her dressed in clothes fitting her position. This helps raise a wall between her and the lustful Conan, who had been promised something else than just gold for his services, and the transition from scared and naked dancer to authoritative ruler is graphically much more impressive when presented that way than in the original story (and than in the SSoC adaptation), in which the lady just tells Conan who she is.

I am pretty sure that Gess will be the target of outraged comments for not updating The Man-Eaters of Zamboula to suit modern sensibilities. The sexism and racism of the original story are still there, and I, for one, couldn't be happier for this steadfastness in adapting an old pulp story; as long as no one is making excuses for racist or sexist characters, I don't mind them being racist or sexist. The Hyborian Age was simply not an enlightened one, and it would be as wrong to pretend otherwise as to pretend that the lions in Tarzan are vegetarian.

Like the preceding books, this one has a text piece by Patrice Louinet, on the genesis of Howard's story. It is clearly not one of Louinet's favourites, and he sees it as purely commercial (which, in all honesty, it pretty much is). Following the tepid reception of Howard's brilliant Beyond the Black River (which didn't warrant a cover illustration) and the outright rejection of The Black Stranger, Howard resorted to a tried and true formula: a simple plot in an exotic land, with a naked girl in a kinky scene sure to get the glorious Margaret Brundage treatment. Howard might have wanted to experiment more with his prose, but he knew which buttons to push to get Farnsworth Wright to accept a tale and give it the Weird Tales cover spot.

The book also has a few pin-ups that aren't bad, but not that special either.

Altogether, because of the excellent artwork and especially the very faithful adaptation of the prose story, this would be my second-favourite book in this series. (The Frost Giant's Daughter is probably unbeatable at this point!)