The Sandman: Volume 8 – Worlds' EndOriginal publication:

The Sandman #51–56 (July 1993 – December 1993)

Script: Neil Gaiman

Artwork: Bryan Talbot (pencils)/Alec Stevens (pencils & inks)/Mark Buckingham (inks)/John Watkiss (pencils & inks)/Michael Zulli (pencils)/Gary Amaro (pencils)/Dick Giordano (inks)/Michael Allred (pencils & inks)/Shea Anton Pensa (pencils)/Vince Locke (inks)/Steve Leialoha (inks)/Tony Harris (inks)

Publisher's synopsis

Publisher's synopsis:

Reminiscent of the legendary Canterbury Tales, THE SANDMAN: WORLDS' END is a wonderful potpourri of engrossing tales and masterly storytelling. Improbably caught in a June blizzard, two wayward compatriots stumble upon a mysterious inn and learn that they are in the middle of a "reality storm." Now surrounded by a menagerie of people and creatures from different times and realities, the two stranded travelers are entertained by mesmerizing myths of infamous sea creatures, dreaming cities, ancient kings, astonishing funeral rituals and moralistic hangmen.OK, on to

The Sandman Volume 8, "Worlds' End".

Just like the earlier volumes "Dream Country" and "Fables & Reflections", "Worlds' End" is a collection of short stories. The difference with this volume is that these stories are all inter-related, insofar as they are all presented within the framing device of a group of people gathered at an inn telling stories to each other to pass the time. The thing about this particular inn which is special is that it is located at the worlds' end – that is, the end of multiple different worlds and realities. As such, the patrons are all travellers who have been caught up in a "reality storm", which has disrupted many different dimensions and worlds, and they have all sought shelter at this inn.

This set up strikes me as being a rather Chaucerian concept – something that the blurb on the back cover of the book refers to. By gathering his characters at an inn, and then having each one recount a story from their own respective realms, author Neil Gaiman is using a set up that is very reminiscent of

The Canterbury Tales. This is no doubt intentional and, of course, the way in which Chaucer focuses on the stories themselves in

The Canterbury Tales, rather than the actual pilgrimage to Canterbury, is very reminiscent of how Gaiman focuses on stories and the art of storytelling in

The Sandman, rather than just relating the adventures of the central cast. In fact, in some of the tales presented here, Gaiman actually nests stories within stories – creating an effect somewhat like a literary Russian doll.

As for Dream (a.k.a. Morpheous), he barely features in this volume at all, which isn't all that unusual in

The Sandman – especially in the volumes that feature stand-alone tales like this. Instead, Gaiman gives us a cast of centaurs, faeries, humans, and necropolitans, all killing time as they wait out the "reality storm". As for the inn itself, I must say that it looks very cosy, and I certainly had a nagging desire to visit the place as I read the book...

Artist Bryan Talbot nails the cosy ambience of the inn with his gorgeous rendering of the building's interior, while Danny Vozzo's warm colours also accentuate the welcoming atmosphere. The artwork works brilliantly to conjure a place that really does feel like a shelter or sanctuary, which is important to the verisimilitude of the entire book, I feel. Although Talbot draws all of the scenes set in the inn itself, each of the tales features its own artist, which gives them all a unique flavour. Talbot's art ties the whole narrative together nicely, while still allowing each of the stories to exist in their own realms.

"Worlds' End" opens mundanely enough, with a young man named Brant Tucker driving a car towards Chicago at night time, while beside him sleeps his co-worker Charlene Mooney. Bizarrely, although it is June and the height of summer, it begins to snow. When a cloven-hoofed, demonic goat-like creature steps out into the road ahead of the car, it causes Brant to lose control of the vehicle and crash into a tree. Brant is shaken, but essentially unharmed, but his female companion is much more seriously injured. Brant then hears a strange, disembodied voice which guides the pair to a mysterious old inn. Inside, they find a motley collection of mystical creatures, including a centaur healer who tends to Charlene. After sleeping for a few hours, Brant awakens to find that Charlene has joined the other inn patrons, so he takes a seat, just as a gentleman named Mr. Gaharis begins to tell a story.

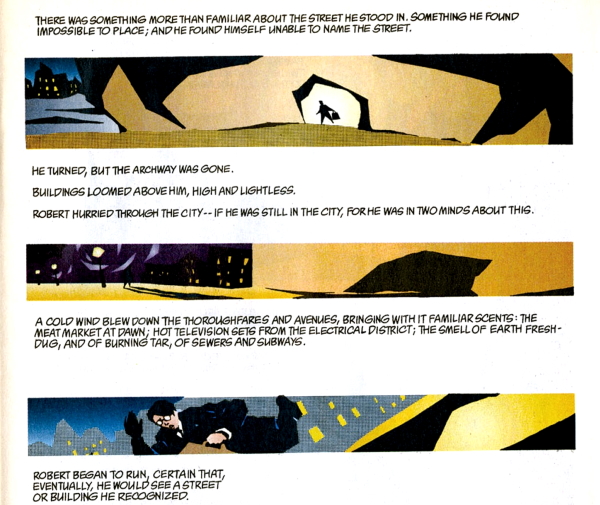

Gaharis's story concerns a young man named Robert who works in an office and likes to spend his lunch-hours wandering around the streets of the city. One day he gets onto a strange looking train and crosses paths with a pale man who we recognise as Dream. From then on, he becomes lost in a deserted city that suddenly looks very different to the one he walks around everyday. It seems that either Robert is dreaming of this strange city or it is the city itself that is dreaming and Robert has somehow become trapped in the metropolis's dream. The question being posed is if the city is indeed dreaming, then what will happen if it should wake up?

*Sigh* Where to start with this? I think Gaiman wants the reader to regard cities as having distinct personalities, which they most certainly do, if only in the most loosely literal of ways – you know, as in, "Paris is a romantic city" or "Glasgow is a hard city." The trouble is, I find the idea that maybe cities can have dreams to be cringe-inducing in the extreme. It's the kind of lame story idea that I would have come up with at school for a fiction essay when I was about 12! I mean, sure, Gaiman's execution is of his usual high standard, but the basic concept sucks. Frankly, I expect better of him.

As an aside, the whole "personality of the city" thing kind of reminds me of some of Will Eisner's city-centric stories, such as

New York: The Big City or

The Building. Anyway, although the story may not be much cop, artist Alec Stevens does a good job of capturing the paranoia and claustrophobia of this tale of a man trapped and alone in an unfamiliar cityscape...

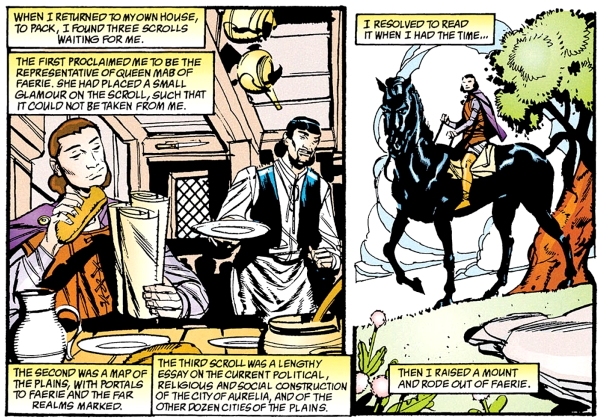

The second story is told by a faerie named Cluracan, who we have met once before in "Season of Mists", in which he handed his sister Nuala over to Dream as a gift from Titania, the Queen of the faeries. Here though he is sent on a mission by Queen Mab (of British and European folklore) to the grand and once-glorious city of Aurelia, in order to prevent its current ruler from uniting other cities under his rule, and thus posing a threat to the faerie realm. Cluracan achieves his goal – with a little help from Dream and his sister Death – by essentially using faerie magic to plant malicious rumours among the city folk of Aurelia about their ruler, which ultimately leads to his death. The art in this story is very nice and captures the quasi-classical, quasi-medieval flavour of the story well...

One thing I want to note is that I find it amusing that Cluracan lets us know up front that his story may not be entirely reliable and may be enhanced by a few untruths to "add verisimilitude, excitement, and local color." Yeah...well, aren't all stories?

The third tale is told by a lad named Jim and involves a sea voyage that he once took, in which it is revealed that "he" is really a "she". This seems to me to be a fairly well used trope in nautical tales; I'm sure I've encountered this idea of a girl posing as a boy sailor before in books or on TV, but I can't for the life of me remember where. Anyway, the story revolves around this girl trying to pass herself off as a boy so that she might get to have shipboard adventures and explore the world. Dream's seemingly immortal friend Hob Gadling also plays a part in this tale, and like all good seafaring adventures, the story features a run-in with a sea monster. The double-page splash of the creature by Michael Zulli and Dick Giordano is really spectacular...

This nautical tale is a pretty riveting yarn in and of itself, but if I were to probe a little bit deeper in search of subtext, I suppose I'd hazard a guess and say that the story is really about the secrets we choose to hide and the ones we choose to reveal. Maybe? I dunno...I'm reaching probably. Anyway, this is a really good yarn that needs no sub-textual "message" to be enjoyed.

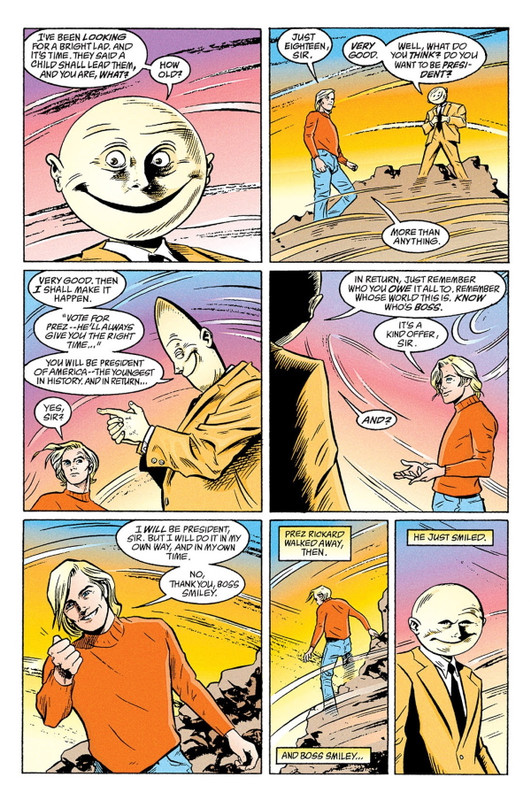

The fourth story is told to Brant by a mysterious Asian gentleman, just outside the young man's bedroom at the inn. The story centres around Prez, who Wikipedia tells me is an old DC character who appeared in a short-lived comic series by Joe Simon and Jerry Grandenetti in 1973 and 1974, and who became the first teenage president of the United States. So, this is another example of Gaiman inserting obscure DC Comics' characters into

The Sandman, as he had done on a few occasions during the early part of the series. If you've been following my reviews, you'll know that I never much like it when Gaiman does this, but this story about Prez (titled "The Golden Boy") is actually a really good read.

I'm not 100% up on my knowledge of obscure DC characters, so feel free to correct me on any points that I may have gotten wrong, but I think "The Golden Boy" is essentially a re-telling of how "Prez" became President of the U.S. (though I'm not sure how accurately it jibes with the early '70s series). Anyway, the story tells of a utopian, Day-Glo coloured alternate America in which Prez rises to the position of President, while being menaced and tempted by the, frankly, terrifying-looking Boss Smiley...

Rather than being a meditation on, or a deconstruction of, American politics, as you might expect, I think that Gaiman is actually more concerned with the allure of fame and influence here. Specifically what a person may or may not be willing to sacrifice in pursuit of those things. There's also an attendant examination of whether a political leader who aims to be fair and ethical can adhere to those noble principals without having to compromise their vision.

The fifth story that is recounted around the table at the Worlds' End Inn was my favourite of the lot. It is titled "Cerements", which my trusty Faber English Dictionary informs me is the name for a waxed cloth used for wrapping the dead or any kind of burial clothes. The story is recounted by a pasty-faced necropolitan named Petrefax and is set in the necropolis of his homeworld. What I found interesting about this story is that, although I enjoyed it overall, it was kind of boring, rather thought-provoking, and strangely beautiful too. A weird mix, to be sure!

The story centres around the relationship between the necropolitan masters and their apprentices, and is chock-full of Gaiman's ruminations on mortality. As for the necropolitans themselves, these pallid-looking beings celebrate death and pride themselves on taking care of the deceased and guiding their spirits to the afterlife.

Perhaps more than any other chapter in this book, "Cerements" is the one with the most horror elements in it. For example, at one point Petrefax describes an air burial, in which a dead body is dismembered and laid out on a lofty clifftop, as birds of prey are encouraged to peck at the body parts until nothing is left. However, while this might be the most gruesome part of "Worlds' End" visually, it also strikes me as one of the most moving. I mean, a so-called air burial of this type seems to me to be a rather beautiful way to dispose of a human body. It makes me wonder whether such a practice has any historical authenticity. Did any civilisation ever practice "air burials" of this kind? Shout out if you know.

Following the air burial scene, the necropolitans sit down to eat around a camp fire, and it is here that Gaiman gives us the Russian doll-like stories-within-a-story that I mentioned earlier. The necropolitans tell stories to each other while they eat – all within the context of Petrefax's story to his fellow drinkers at the Words' End Inn. So, this inventive narrative device has our storyteller telling us a tale of other storytellers, who in turn tell us stories about storytellers. Like I say, it's like literary Russian dolls.

At this point in the book, with the storytelling more or less over, Brant's female companion Charlene complains about the male-orientated, chauvinistic nature of the stories that have been shared. Perhaps this is a commentary by Gaiman on the male-centric nature of mainstream American comics in the early '90s? I dunno, but I definitely feel as if Gaiman is making an important point with this scene. Anyway, while complaining about the sexist content of the stories, Charlene also admits that she has nothing better to offer, and as a result settles into a cynical and bitter recap of her own life story.

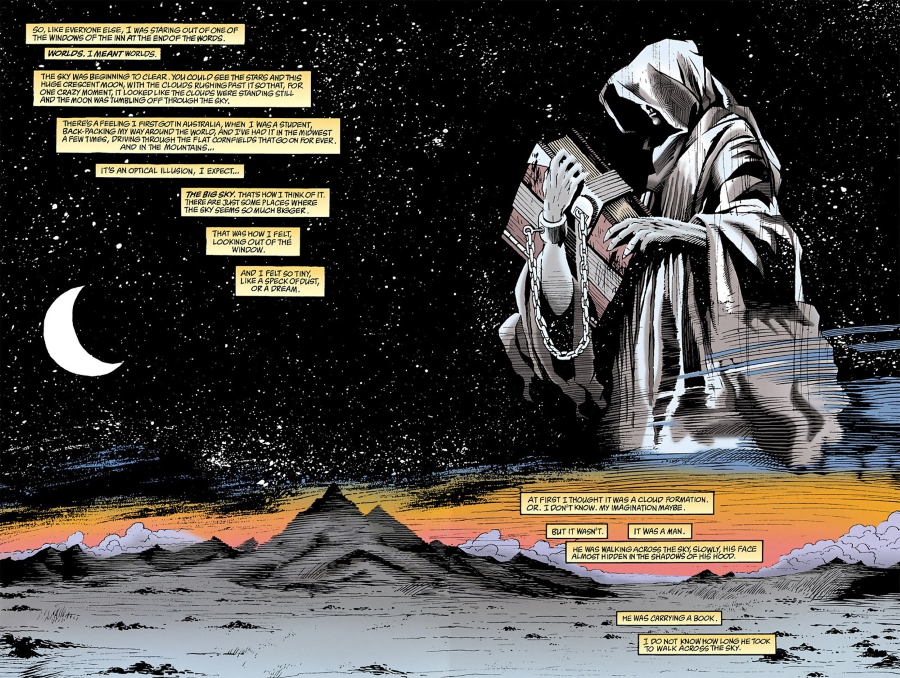

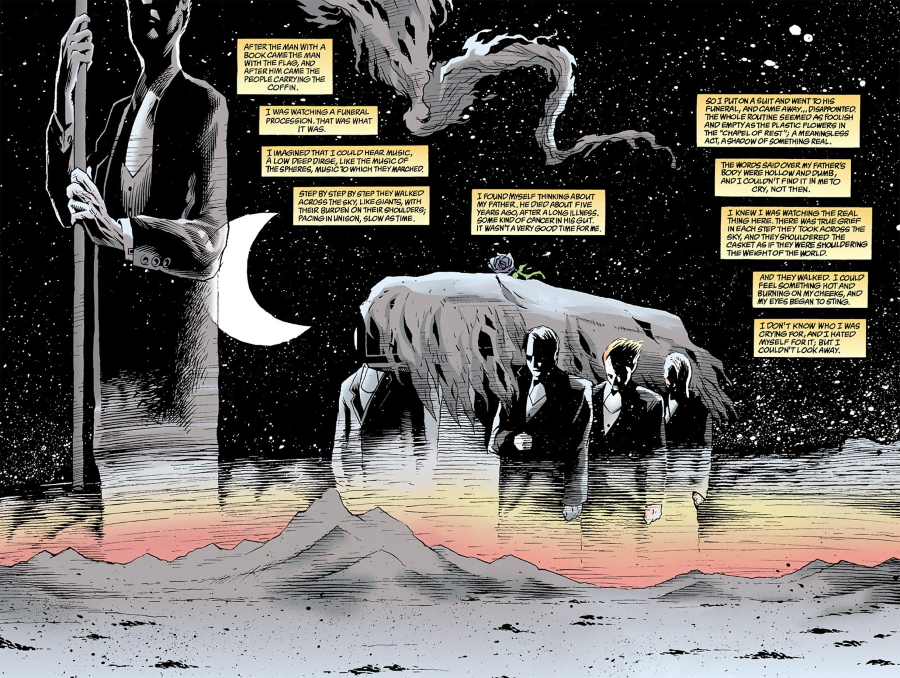

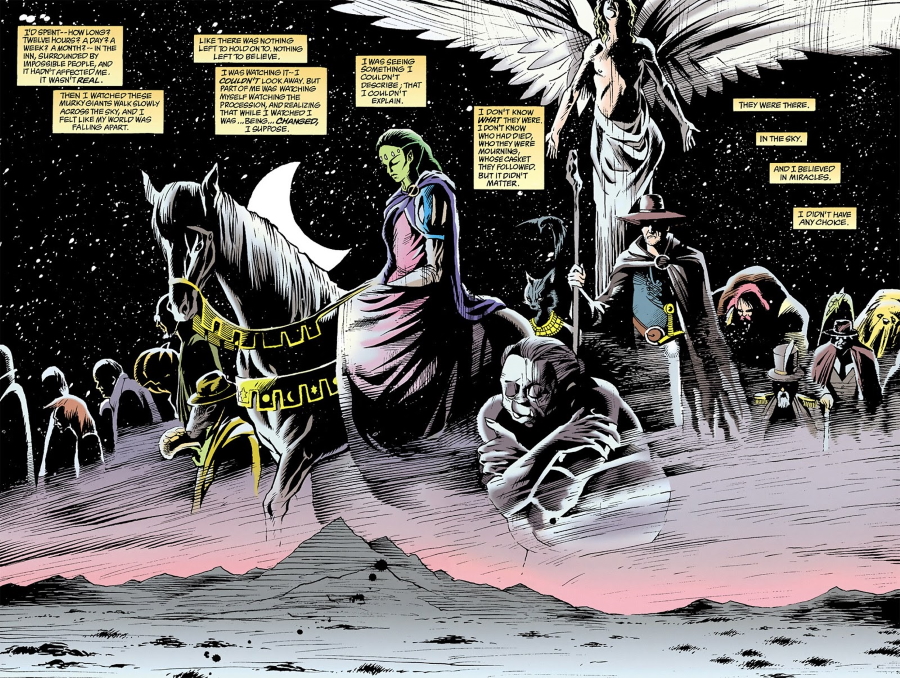

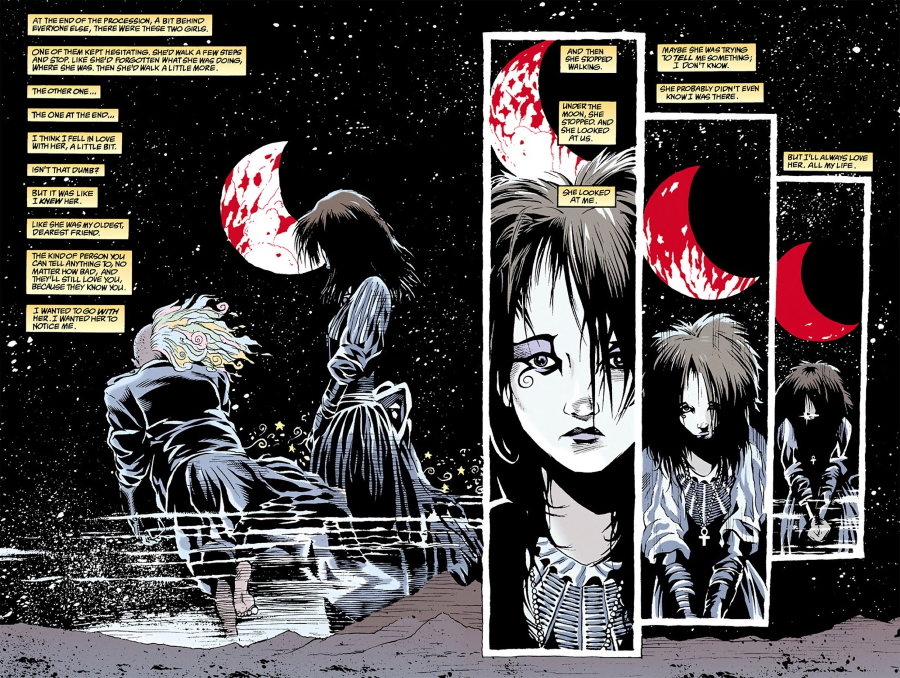

It is at this point that one of the travellers at the inn catches sight of something strange outside the window. As the patrons gather against the inn's windowpanes, they see a breathtaking spectral funeral procession consisting of Gods, faeries, and a number of characters that we've seen before in the series marching across the night-time sky. Destiny of the Endless marches solemnly at the head of the procession, while Desire and Death mournfully following at its rear. Gaiman's writing is amazing here and the whole sequence is beautifully depicted by artist Gary Amaro across four double-page spreads. It's such a beautiful sequence in fact, that it deserves to be reproduced here in full...

The significance of this moving scene is unknown at this point, but clearly it can't be good news. Obviously something major has gone down and the way in which Death looks at us in those final panels gives me shivers. Of course, I have my own theory about what has transpired, but regardless of whether I'm right or wrong, I'm pretty sure that it is the cause of the "reality storm" that has stranded our travellers at the Worlds' End Inn. No doubt more light will be shed on this supernatural funeral cortège in the next volume, but suffice it to say, Gaiman and Amaro have created a scene here which is hauntingly moving and likely to stick in the reader's mind for some time.

By the close of the book, the "reality storm" has abated and our stranded travellers must decide whether to continue on with their journeys or start new ones. Ultimately, some, like Charlene, elect to remain at the Worlds' End Inn, rather than return to the less than satisfactory realities of their lives. Brant chooses to return to our reality, but upon arriving home he discovers that it is a reality in which his friend Charlene has never existed.

Overall, "Worlds' End" was an enjoyable, if slightly uneven read. I find that the quality often varies in these collections of short stories which Gaiman periodically serves up, and there's certainly nothing here approaching the calibre of earlier stand-alone tales like "Calliope" or "A Midsummer Night's Dream" or "Ramadan". Still, I did very much like the unification of the stories through the Chaucerian narrative device of them being told by guests at the inn.

Bryan Talbot's art is lovely throughout and I really enjoyed all the little "Easter eggs" that Gaiman sprinkles throughout his narrative. Some of these "Easter eggs" refer to past events in

The Sandman (like Joshua Norton of San Francisco, the first Emperor of America or Cluracan's sister Nuala now belonging to Dream, for example) and some refer to real world or literary references (like Buddy Holly having died in a field in Iowa or the ship "The Spirit of Whitby" being a reference to Bram Stoker's

Dracula).

Ultimately, I feel that "Worlds' End" is an enjoyable but inessential volume of

The Sandman. Although it is an good read and quite profound in places, it never reaches the heights that I know the series is capable of. That said, the ending, with the funeral precession across the sky, was a really gripping climax. What the hell has happened? Is Morpheus dead?!! Man, I've gotta hurry up and read the next volume!