Day Twelve (#1)

The Legion of Super-Heroes (Adventure/ Superboy/The Legion of Super-Heroes)The second comic I bought on my own was

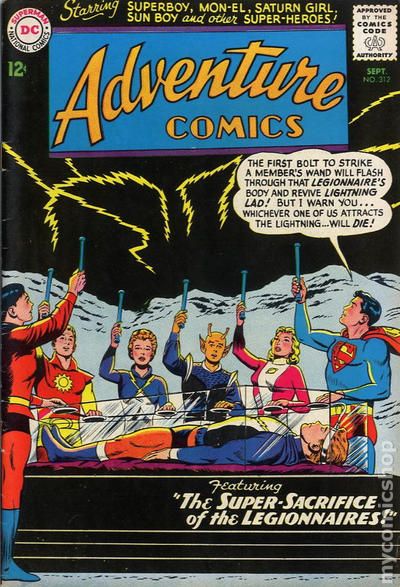

Adventure 312, in July of 1963, the first issue of

Adventure Comics I had ever seen. It remains indelible in my memory, and I became a loyal fan of the Legion as a result. (I’d say lifelong, but I lost interest during the Giffen era. Aged out, I guess.)

If there’s anything to the notion that it’s the first impression that is most powerful, I think of the cover of

Adventure 312. To quote myself from another thread, “I loved everything about it, but I was especially grabbed by the deep black cover… It seemed important, but… this was no celebration, but [an occasion for] solemnity, a serious story about sacrifice.

And there was the logo. I couldn’t put my finger on it then, and can barely do so now, but there was something so cool about the lettering, the color scheme, and the very name of the comic that I found irresistible.

(How many comics sold because of Ira Schnapp's lettering alone?)

Then there was the word “Legion…” Impressive, conjuring up the majesty and the glory of the Roman legions. Plus there was the word “Legionnaires,” which always meant adventure to me. I grew up loving movies about the Foreign Legion and the old TV show, “Captain Gallant of the Foreign Legion” with Buster Crabbe, which ran in all its grainy glory on Channel 9 in New York.

You can see why I had to buy that comic.

Even today, the starkness and solemnity of the cover of

Adventure 312 remain etched in my memory. However, unlike many of the other great covers of the time, its power was actually matched by the story that accompanied it. It was heady stuff for a kid of nine, immersed as it was in the mystery of death, the nobility of true friendship, and, of course, the theme of sacrifice that ran through the entire story.

And that those themes reappeared all the time during my many years reading the Legion. Like the biographies of sports stars and people from American history I liked as a kid, and books like “Johnny Tremain” and the Hardy Boys, Legion stories (in those early days, anyway) were about characters just a little older than I was. Reading about those older kids helped me to socialize by proxy, to gain some insight into how to behave, what to say, and what would be expected of me when I reached the age of the characters I read about.

The stories, a nice mix of “save-the-universe” tales and soapy melodrama, maintained a delicate balance that kept the title from getting too predictable, with the melodramatic aspects slipped into the epics, which was just fine.

In the stories of the Legion, unlike so many other DC stories, things actually happened; these were not Imaginary Stories, hoaxes, or dreams of the kind that filled the other Weisinger titles.

Over the many years that I followed the Legion in the Silver Age, Lightning Lad died, was resurrected, though only at the cost of another’s life. That was a zero-sum game those Legionnaires were playing on the cover of Adventure 312. Lightning Lad later lost his arm in battle; Star Boy was expelled for violating the Legion’s code against killing; Triplicate Girl lost one of her bodies in battle against Computo; Kid Psycho lost years from his life every time he used his virtually limitless power; and of course, the heroic Ferro Lad died an irreversible death.

I loved that events in one story would actually affect future events – yes, Star Boy got back in, but it took a long while -- and I loved that there were pro- and anti-Star Boy factions among the Legionnaires themselves. The jury’s votes were public, so as a reader, you gained even more insight into the various members as they weighed in on an issue fraught with high emotion and legal complexity. Not the usual Silver Age fluff.

Another plus: Unlike virtually every other DC comic, the Tales of the Legion of Super-Heroes paid a great deal of attention to continuity. Only in the Legion stories was the date of the year in which the stories took place identified; it was always a thousand years after the year in which they were published. It was as if these adventures, unlike those of any other DC characters, were taking place almost in real time.

There were some seriously good stories, too: the two-issue battle vs. Computo the Conqueror; the saga of Lightning Lad’s trials and his eventual resurrection; “The Lone Wolf Legionnaire;” the trial of Star Boy; the battle against the Sun-Eater; and the dramatic debut of Mordru jump to mind.

As innocent as the adventures of the Silver Age Legion may seem now, there was flowing through them a subtle current that was quite appealing to kids... well, to me, anyway. Time after time, this gaggle of super-powered kids was charged with the protection of the universe by befuddled, apparently incompetent adult authorities.

Running beneath the surface of the entire Legion saga was the notion that the Legion had a chip on its collective shoulder. It smacked a little of the chutzpah displayed by Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland in movies like “Babes in Arms:” “Hey, you adults, you ain’t so perfect. We can show you all a thing or two, even though we may be just kids!”

I was thrilled that these kids, at least, had the power to solve problems on their own. And they suffered trying to do so, because tragedy could strike without warning when the entire universe was the setting.

Another reason to like the Legionnaires, though, was that despite all those adult responsibilities and all that heroism, they acted like teenagers. Like all high school kids, the Legionnaires belonged to tribes, but readers liked them all, either because they were big guns like Mon-El and Saturn Girl, or because they were, well, weird, like Bouncing Boy and Matter-Eater Lad.

They formed cliques, clung to their significant others, lost their tempers, stalked off in fits of pique, stoked the fires of secret crushes, suffered from various romantic ailments: petty jealousy, unrequited love, star-crossed love and betrayal of all kinds. And though they were often misunderstood by adults, they rarely gave each other the benefit of the doubt, either, instead tending to gang upon any Legionnaire who acted in a way they thought was un-Legionnairey.

In the end, it seemed to me, the Legionnaires just wanted to do what all kids have always wanted to do: prove to an often dismissive adult world that they were capable of rising to a challenge, and far exceeding the low expectations of dismissive adults.

And that is why they are still big favorites of mine.