|

|

Post by MWGallaher on Jun 9, 2023 14:57:35 GMT -5

His avoidance of feet is an insignificant complaint, really just a game, where once it's pointed out, you can't help but notice it. My problems with his work are more substantial, and it's a long list. He has practically zero ability to stage his panels against a convincing background set, choosing to place the action in rooftops, empty warehouses, or just in a void. If it's not a warehouse, he'll draw it like a warehouse anyway. This is one of his pages I found particularly hilarious, showing the luxurious traveling accommodations inside the Avengers' quinjet:  He can botch placement of figures in even the most rudimentary of backgrounds: where are these characters in relationship to the floor, the one-way mirror?  He struggles to consistently or convincingly position multiple figures within the same panel. Does this girl appear to be 11 steps up from the guys? If the guys are standing on the same surface, how far below the panel are their feet? Is the big guy really supposed to have arms longer than his buddy's full height?  No one ever seems to be in their environment, and usually not in the same space as the other characters. Of all the techniques artists have to convey three dimensions--perspective, lighting, even just making distant characters smaller than closer ones, he seems to only have mastery of one, the very simplest: closer characters overlap farther ones. That's one reason I think of him as a "Colorforms artist": it appears that he takes his established set of poses and plops them down somewhere on the page, roughly coordinated with whatever crude background there is, and calls it done. |

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on Jun 8, 2023 5:42:40 GMT -5

The story is by Robert Kanigher and he and Murry Boltinoff claim creation of the OSS Feature, though Bart Regan wrote the earliest stories. Ric Estrada again provides the art, after ER Cruz had been handling it, in GI Combat. Having recently read through some scans of early issues of DETECTIVE COMICS, I immediately suspected "Bart Regan" was a (quite appropriate) pseudonym:  The GCD, which credits "Regan" with only these few O.S.S. stories, tags it as a pen-name for Kanigher. Not being a war comics fan at the time, I passed on that final issue of SHOWCASE. I've since found the O.S.S. backups to be quite appealing changes of pace, and grown quite fond of Estrada's art, which I never liked when it would pop up in a superhero story. |

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on Jun 7, 2023 9:38:39 GMT -5

Batman was a lot more relatable in 1940, but he was still capable of doing things no normal man can bring himself to do:  |

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on Jun 6, 2023 17:03:21 GMT -5

With current "franchise" marketing standards, various types of Oreos take up about 1/3 of the cookie aisle real estate in my local grocery store. Even so, they still haven't marketed the one variation I really, seriously, genuinely want: traditional cookie flavor with no creme.

|

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on Jun 5, 2023 8:20:12 GMT -5

It's quite an honor, almost a difficult one to acknowledge given my modest nature. Thanks, and congratulations to all winners and nominees.

These past couple of years have been the most rewarding for me. You all were my primary social network during the pandemic, and have been inspirational in reinvigorating my interest in comics and encouraging my explorations of things like Hourman, Marvel Westerns, and jungle comics. I keep recalling a prophecy of doom made years ago, that despite this forum's generally genial, respectful, and positive tone, it would ultimately devolve into an unpleasant and bickering community. We've had conflicts now and then, and hurt feelings, but we're still maintaining some of the highest standards of online interaction that I've seen in any social media. Long may it remain so!

|

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on Jun 3, 2023 7:45:37 GMT -5

In June 1973, I bought:  I think this was the first time my Mavel purchases exceeded my DC purchases. The King-Size Spider-Man, Fantastic Four and Conan annuals delivered some important reprints, reprinting the second Spider-Man magazine from the 60's, Reed and Sue's wedding, and Barry Smith stories that made me like Conan. Valuable education for a new Marvel aficionado. I always bought Defenders, Man-Thing was good but no Swamp Thing, and Ghost Rider had me excited after splitting off the new Son of Satan series in its final Marvel Spotlight installment. Thing team-ups were a welcome follow-up to Ant-Man in Marvel Feature, and I was digging being in on the early days of a new Dr. Strange series in Marvel Premiere. Among Marvel's many monthly reprints, I was blown away by the quality of Kirby's Thor in Marvel Spectacular, and I was eager to catch up on the Swordsman after his recent reappearance in Avengers. Marvel Team-Up continued to disappoint, but I bought it, even though I didn't really like Captain America. Red Wolf caught my eye by moving away from the Western setting that I didn't care for (back then). And I enjoyed being in on the ground floor with another new superhero, Brother Voodoo. I was still enjoying one of my favorite Defenders, the Sub-Mariner, in his own comic, and Tomb of Dracula was incredible stuff. As an SF fan, I liked Worlds Unknown's adaptation of The Day the Earth Stood Still, and Savage Tales #2 delivered more Smith Conan, so I was eager to buy. There was no better value in my mind than DC's Super-Specs, and this one gave us the complete original Two-Face trilogy. I'd loved this villain since his recent B&B appearance. The second Black Orchid appearance was fun, and I was smart enough to pick up Neal Adams' classic Joker store in that month's Batman. JLA was continuing its annual JSA team-up and reintroducing more Golden Age characters in the Freedom Fighters, so that was irresistible. DC's new reprint line held its appeal; I was surprisingly happy with Boy Commandos, and Secret Origins, well, of course I was a sucker for an origin story, even if Vigilante and Kid Eternity weren't special favorites. I'd eagerly awaited Plop, and Sword of Sorcery was a favorite throughout its short run. I had become firmly committed to the Legion, and I stubbornly stuck with Shazam, and gave an inexplicable try to Strange Sports Stories. Swamp Thing was a must-not-miss, and I was rewarded when I finally gave Jonah Hex a shot with a purchase of Weird Western--it was terrific stuff! |

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on May 29, 2023 14:22:46 GMT -5

I'm surprised by how clearly I can remember certain pages within that I must have colored, including the image that I had in my mind when I first went looking for this thing:  I think I'd have been very displeased at having those stupid numbers visible on my finished coloring job! I don't recall ever seeing that in coloring books. And thinking as a kid, I wonder how many youngsters concluded from that coloring guide that Batman's cape was supposed to literally be black and blue vertical strips? Plus I'd be annoyed that they didn't provide a guide for every area--how's a kid supposed to know what to do with those stripes on Robin's sleeves or the trim of his trunks? I've got memories of a couple of coloring books from my pre-comics days, a "My Favorite Martian" and "Valley of the Gwangi". Sci-Fi comedy and dinosaurs for this lad! |

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on May 28, 2023 19:08:15 GMT -5

|

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on May 28, 2023 16:54:52 GMT -5

I thought I'd get back to this thread and finish it off; following this look at a couple of Indian stars, there are only 5 to 7 topics to cover (I'll be addressing 3 characters in a single post, for reasons which shall be obvious). So let's get back in the saddle... Long before they published RED WOLF, Marvel—or Atlas, that is—had two other series with Native Americans as leads. The first was RED WARRIOR, which ran from #1, January 1951, to #6, December 1951. This was one month after APACHE KID #1, but Apache Kid was half-native, and a big part of its premise was that the lead character could, in his “secret identity”, pass as a white man. This makes RED WARRIOR Atlas/Marvel’s first series starring a non-white lead character.  Red Warrior’s adventures were illustrated by Tom Gill, who followed his RED WARRIOR work with an impressive 107 issue, 11 year-long stint drawing THE LONE RANGER comics for Dell. Gill drew all the stories starring the cover character, and all of the covers, except for the final 6th issue, which sported a Joe Maneely cover. Gill’s art is clean, clear, and wholesome-looking, a little stiff, but pleasant to look at. So, what’s Red Warrior’s story? He’s the son of Chief Grey Eagle of the Comanche, whose prayer to Manitou blessed him from birth with strength, wisdom, courage, and exemplary morals. He’s raised to learn all of the native skills, not just the hunting and fighting skills of the men, but the healing and mending skills of the women. Once he has surpassed the level of his teachers, Red Warrior continues to study from nature, learning the benefits of all the plants and the ways of all animals. After eight drunken white men attack the village while Red Warrior is away, Red learns of the wicked ways of the palefaces, and he slaughters them in vengeance:  These are the last white people to appear in this issue of RED WARRIOR. In the second story, Red Warrior fights against a rival, Flaming Arrow, whom Red ultimately kills in combat:  A short tale of an Indian boy follows, drawn by George Tuska, and the final story sees the tribe suffering a drought, until Red Warrior discovers a hidden valley with game and fresh water, saving the tribe. Following issues featured a blend of stories focusing entirely on the affairs of Red Warrior’s tribe and tales of his encounters with white men. Red Warrior has lots of bad experiences with evil white men, and even displays a hint of supernatural power by summoning lighting from the Great Spirit:  Over all, the stories mostly focus on Red Warrior’s tribe, not with the white men’s town. Red Warrior does have good relationships with the whites—at least the respectable ones—but delivers his share of Western justice to the badmen. His final story is “The Trail of the Marauder”, which sees Red Warrior’s best friend become mad with the delusion that he is a wolf. At the climax, Red Warrior gets through to his friend, who jumps off a cliff rather than subjecting his friend to the burden of killing him:  I liked RED WARRIOR a lot. I had become a Tom Gill fan by the time I got through a few issues, and it was refreshing to see most of the stories revolving around the Indians, not white settler. But after all, the covers all declare that these are “Tales from the Land of the Redmen!” ARROWHEAD came along a few years later, with his own comic debuting with #1 in April 1954, but running only 4 issues, through November 1954.  All of Arrowhead’s adventures were penciled and inked by Joe Sinnott, whose work looks to me to be highly influenced by the team of Will Elder and John Severin; add a little “chicken fat” and funnier script and this panel could have come straight out of an issue of MAD:  But ARROWHEAD is serious business. Check out the grim vow on the introductory splash:  Arrowhead is the son of Chief Bear-That-Walks, leader of a tribe of Pawnee Indians, and is, as one would expect, exemplary over all others in fitness, looks, and the skills and weaponry of the Indians. He’s got dibs on the most coveted maiden in the village, but he also has the enmity of the tribe’s medicine man, Snake Fang, whose own son, Running Wolf, is rival to him in games and romance. Later Arrowhead learns of the threat of the Palefaces, and is taught to despise them, even though he has never seen one. When Arrowhead goes to his ritual test of manhood, staying alone in a cave, he dreams of shooting a white man with his arrow, before waking and then nearly dying in a battle with a huge bear. White trader Pete Frame finds the unconscious Arrowhead and returns him to be nursed back to health at the Pawnee village, hoping to earn the respect of the Indians. They are grateful, but not grateful enough to reveal where the tribe gets the gold to make the jewelry they wear! Weeks later, Arrowhead’s family never returns after a trading trip and in response, Arrowhead—finally recovered--goes in search, only to find them all slaughtered, with evidence that the killers were a tribe of Crow Indians. He finds them, slaughters them, and gets arrested himself by white men who don’t care that he’s not one of the Crow who have been causing trouble. A “good” white man, Andy Crockett, helps Arrowhead to escape from jail and returns to his tribe, only to find Snake Fang in charge, trading gold to Pete Frame for firearms. He kills Snake Fang when he learns that Snake Fang, not the Crow was behind his family’s death, but is then branded a renegade by both the Indians and the White Man. It’s a gripping little origin tale, despite the cliché “perfect prince” trope, and despite the intrigues getting a little muddled, between the many attributions of guilt and varying implied motivations of Snake Fang, the Crow, and the white people. I’ll just accept the conclusion, that Arrowhead is left a man without a country, unloved by either of the races, and nursing a grudge against one more so than against the other.  To my surprise, Arrowhead did not temper his hatred for white men at all over the course of his four issue run. His arrows were uniformly lethal, and he tended to fire them directly into the chests of his white enemies every issue. It’s surprisingly discomforting to see this brutality in a genre that was in the process of being neutered with cowboys whose bullets would only bruise hands. I can’t quite decide whether it’s racist because Arrowhead hates white people, or whether it’s racist because it grants that Indian heroes are allowed to murder their enemies while white Western heroes are held to a higher moral standard, or whether it’s not racist but justifiable retribution for historically factual wrongs against Native Americans. I’d love to know what the readers of the time thought of this. How easy would it be for American kids familiar with conventional cowboy heroes to root for an Indian that unapologetically vowed to kill the white man?  When ARROWHEAD was canceled, Atlas was left holding at least one unpublished story, and Western stories are easy to drop in as a back-up story for another title, and thus did Arrowhead’s final published adventure appear in BLACK RIDER #25, the very same month that Arrowhead’s own comic saw its final issue hit the stands. In this untitled story, Arrowhead sees a white man gesturing mysteriously toward the prairie, and then Arrowhead attempts to get news from back home from his old friend Little Otter and some other Pawnees he sees in the area. The group is loaded up with guns and drunk on firewater, all given to them by “a friend” who promised them the Pawnee would soon be able to reclaim their territory from the palefaces. When they turn their new guns on the renegade Arrowhead, he knocks out the drunken men, telling them to go back to their lodges and sleep it off. Almost immediately, Arrowhead is under attack by white men on horses. Arrowhead takes care of them with a few arrows to the chest and returns to the Pawnees he’d tangled with before, only to find that they’ve been shot dead while in their drunken stupor (but then, maybe if Arrowhead hadn’t rendered them completely unconscious they could still have put up a fight).  A.H. finds a cabin burning, with the obvious intent of implicating the Indians, who are known to use flaming arrows, and is then captured by another group of white men, who plan to hang the Indian in town as “an example to the rest of your breed.” He breaks free, but is recaptured when the men threaten to shoot his horse, and Arrowhead ends up in the town jail. On the final page, the white man from page one appears, offering a deal: rouse the Pawnees to kill local settlers and start a land war, so that he can mop up and take control after the mass slaughter. Arrowhead, quite reasonably, refuses the deal, and gets the villain in a chokehold through the jail bars. He ties up the schemer with a rope attached to his horse, Eagle, intending to march him to the townspeople to confess, but the horse dashes off on his own, dragging the villain to his death. In his final panel, Arrowhead praises the lethal instincts of his steed:  That's some terrific pre-Code savagery there! Neither of these attempts succeeded for Atlas, but both of their American Indian-led comics were thrilling, well-done efforts. They demonstrate that there was some room for greater variety in the Westerns than the cowboy heroes and unjustly-branded outlaws that dominated the genre. |

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on May 26, 2023 8:21:47 GMT -5

Classic Cover Contest: 26 May 2023 to 29 May 2023I apologize profusely for my absence and the late start to this week’s contest. I am well, I just got overwhelmed with responsibilities that kept me away from the forum. Among the less onerous of those responsibilities has been yardwork and gardening, so for this unfortunately abbreviated contest, let's do... PLANTSLiving plants, monster plants, anything where plant life is a key focus of the cover, rather than simply set dressing. For instance... WHERE MONSTERS DWELL #14 (cover by John Severin)  The Cover Contest Rules: Post one, and only one, classic cover that fits the theme of the contest. - Cover must be from a published comic book or collected volume published before 23 May 2013. (not a difficult bit of compliance this week.) - Please include the title and the issue number of the comic in bold (e.g. Soldier Comics 8, March 1953) in case some posters cannot see your image. - Covers must be posted before voting begins. - Voting takes place on Tuesday, 30 May 2023, beginning at 12:01 am PST and ending at 11:59 am PST. - Vote by posting the name of the poster whose cover best fits the theme or that you simply like the most in bold. - The winner of the contest is the entrant with the most votes after the voting period ends. - The winner chooses the theme for the next week's contest. - If you don't think the cover fits the theme, don't vote for it; please don't post disparaging remarks about it. - If a cover is more recent than the classic time frame, kindly point it out to the poster, who may then choose an alternate before voting begins. Have fun, everybody!

|

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on May 26, 2023 8:10:58 GMT -5

Sorry for the delay, everyone. I've been overwhelmed by responsibilities and wasn't expecting a win this week! I guess we'll have an abbreviated cover contest, but it will be up soon!

|

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on May 26, 2023 8:05:17 GMT -5

Hoping some New Gods fans can help me out here. I've been reading Secret Society of Super Villains, and on the cover of issue #4, it touts an appearance by The Black Racer. Now, he doesn't actually show up in the issue until the last panel, as Darkseid is punishing Mantis, The Power Parasite, and threatens him with The Black Racer, who Mantis seems legit frightened of. In the next issue, The Black Racer shows up in the background of two panels, then zips off to not be seen again, so... Who is The Black Racer, and why should anyone be afraid of a guy on floating skis, complete with matching ski poles and long flowing yellow cape, who doesn't actually seem to DO anything? Plenty have people have joked about The Black Racer, but in pondering writing an article closely associated to the topic, I realized that Kirby's design for this character was actually very, very clever. And yes, I'm totally serious here. As an innovator, Kirby found many ways to make his characters fly, ways that other superhero artists never thought of. Kirby's flying techniques, at their most effective, evoked unique physical sensations in the reader. We could "feel" the pull of Mjolnir guiding Thor across the sky. Even if we had never surfed, the Silver Surfer's board could be sensed as something that would allow us to immediately change direction with a subtle shift of our weight, unencumbered by the large momentum of a bulky space ship. So what does the Black Racer have going for him? Consider, say, Superman. The artist is drawing him flying. The artist is drawing him flying at top speed. Now, the artist is directed to draw Superman flying even faster. How does the artist convey that? How does the artist suggest even that Superman can fly even faster than he already is? That is the genius of The Black Racer. Even if the reader has, like me, never snow-skied, we know those poles are used to accelerate. We can feel it, just from the image of a skier: ram those poles down, thrust forward, go even faster. Furiously repeat the action...go faster, faster, faster! Even if we never consciously think about it, The Black Racer's equipment conveys the subtle, alarming sense that no matter how fast we try to outrun him, all he has to do is give it another push of the poles and he's gaining on us. Gliding through the air, not the snow, supernatural, unimpaired by physics and friction. The poles symbolize the potential for relentless pursuit, achieving speeds beyond any limit. It's a perfect symbol of Death: the faster we go, the farther we travel, Death is right behind us, always gaining on us, always getting closer. Every tick of the clock is a thrust of those ski-poles bringing The Black Racer closer and closer to overtaking us. The Black Racer. At a glance, we know one thing: no matter how fast he's coming at us, he can start coming even faster. |

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on May 22, 2023 20:03:22 GMT -5

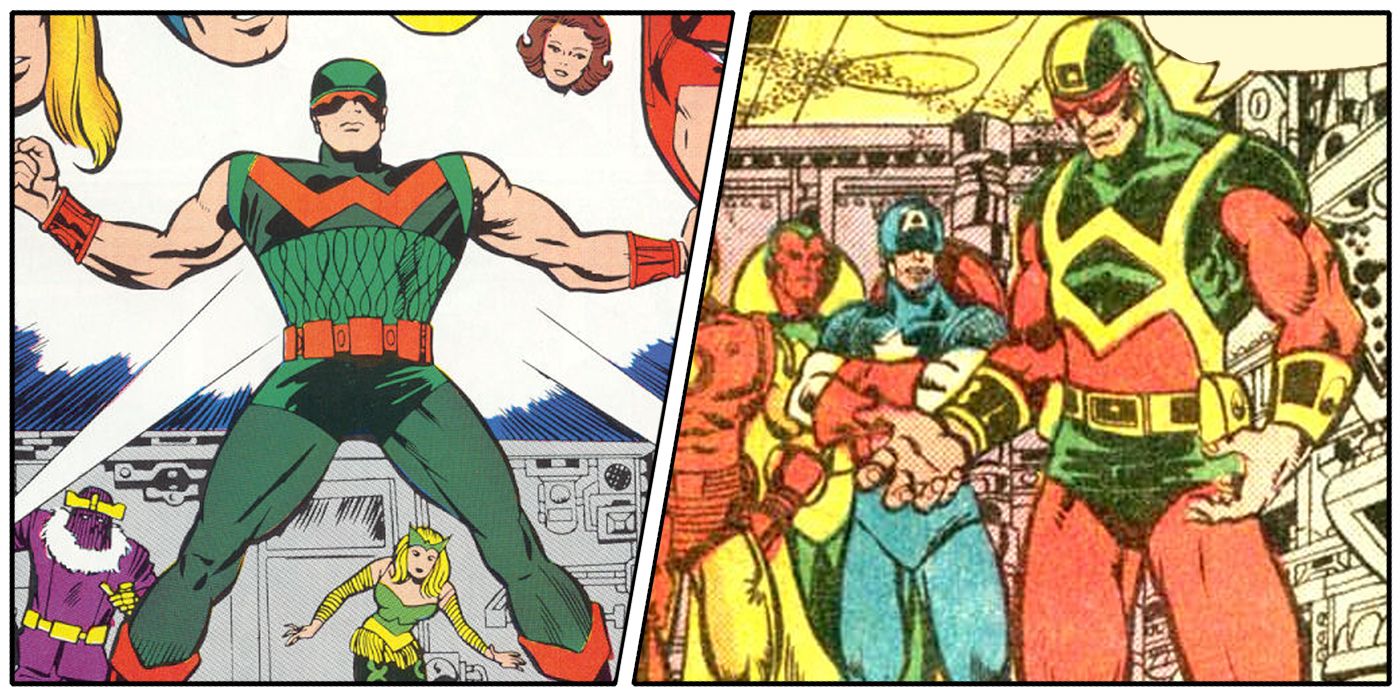

I've always been more of a DC guy than Marvel one, but I've never understood why people don't like Wonder Man's costume. Specifically, either of these:  What am I not supposed to like? Is it an outfit which works on a cover but looks bad in story or something? Is it too busy? Too colorful? I thought color and intensity are boons in superhero comics. Gauntlets, wrist bands, cool looking belt - what's not to like? I'll admit that I may never have read a comic with him in it, but I'm not seeing a problem which a lot of people seem to regard as instantly obvious. I assume at least some Marvel fans thought that wearing your initials on your chest was too "DC" (although there really aren't that many--Superman Family, Robin, Wonder Woman...uh, Geo-Force...). Wonder Man's original costume had the curly filigree on the abdomen, something that always suggested to me that Don Heck designed it. Heck had some very distinctive but not especially good design instincts, and that design is, at the very least, not in keeping with the usual super-hero aesthetic. |

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on May 20, 2023 22:27:28 GMT -5

I had that issue; one of the ones I collected, back in the day. The story is also repeated in the first Avon novel, The Story of the Phantom. The main story adapts the Sunday edition story "The Female Phantom," from 1952. In the original, the Phantom (he is supposed to be the grandfather of the 21st Phantom) goes to rescue a missionary from river pirates. He sneaks aboard their riverboat, but is shot during a fight with the pirates, which Julie witnesses from shore. He is dumped into the crocodile-filled river and Julie dives in and saves him. She brings him back to Skull Cave to recuperate, then makes her own costume to venture out as the Phantom, to rescue the missionary (whom she finds handsome). Julie sneaks aboard and frees the missionary, bu they are spotted. She takes the captain hostage, then gives her pistols to the missionary and swims to shore, for help, rousing the nearest Jungle Patrol garrison. She then disappears and the Jungle Patrol think that the missionary captured the pirates, single-handedly. She then visits the missionary and says she must leave him and she cannot tell him her name. She returns to her brother, who is in much better shape, and cries on his shoulder, because she is in love with the missionary. He concocts a scheme for them to meet, with her in girly frocks and it succeeds and they go off to raise Holy Ghosts That Walk, or something. In the course of things, Diana Palmer, who stays with the Bandar, discovers the costume and tries it on, asking the Phantom how the heck he stands the jungle heat in it. he replies that "You get used to it." Right! The Phantom was ignorant of the female ancestor and locates the story in the chronicles, detailed by his grandfather. Quite frankly, Julie is more competent and assured, in the original Sunday strips, though the comic book has her carrying out more work, as the Phantom. There is not tracking her to the Skull Cave and no capture, either, in the strips. In the later years, after the Phantom and Diana Palmer marry, she gives birth to twins, Kit and Heloise, though they are depicted as children, in the strips in the 2000s. The Defenders of the Earth cartoon did a story, where the Phantom (the 22nd) meets up again with his twin brother, who he defeated in a contest to become the Phantom, succeeding their father. The other brother is angry and jealous and turns to villainy, when they are reunited. The 22nd Phantom is depicted with a daughter, Jedda, who takes on the mantle of the Phantom, in the cartoon, briefly, when she believes her father has been killed. Incidentally, one of the storyboard directors of the series was Pat Boyette, who drew the Phantom's adventures, at Charlton (think he did some Flash Gordon, too). I do wonder why King's own Phantom series would take more liberties, with "The Girl Phantom" clearly being a much looser adaptation of the strip sequence than what they appear to have allowed Gold Key to do. I see that Bill Harris wrote most or all of Gold Key's series, but was hired away from Western to serve as editor on the King run, writing only a few of the stories. Perhaps Harris wasn't as competent at plotting and thus relied more on producing faithful remakes, but as editor was able to hire experienced writers like Dick Wood and Jerry Siegel who could be trusted to come up with their own plots. There's probably some interesting history behind King's brief comic book line; I assume that during the Batman craze of '66 they wanted to get a bigger piece of the pie and figured their well-established adventure features--Phantom, Jungle Jim, Flash Gordon, and Mandrake--would be competitive. |

|

|

|

Post by MWGallaher on May 20, 2023 9:18:08 GMT -5

As long as we’re on the topic, let’s continue with King Comics’ publication run of THE PHANTOM, sampling #20.  In the summer of 1966, King Features Syndicate entered the comic book market, taking back the publication rights to various features from the many newspaper strips that King syndicated in order to package them themselves. Dated August 1966, the King Comics line debuted BEETLE BAILEY #54, BLONDIE #164, and POPEYE #81, clawing the rights back from Western and Harvey. The following month, they started brand new series with FLASH GORDON #1 and MANDRAKE THE MAGICIAN #1, and resumed THE PHANTOM with #18, following Western’s final #17. (In 1967, they would bring JUNGLE JIM back to the stands for one issue, as covered previously in this thread, before giving up on the idea and licensing all seven titles to Charlton.) The first few issues in the King run are obviously burning off some material prepared at Western, as evidenced by the captions and rectangular word balloons never touching the panel borders. With this issue, the text placement comes more in line with the competitors’ approaches. The Bill Ligante art is still rather outdated, but breaking from Gold Key’s curious policies gives the comic a somewhat more contemporary, arguably less juvenile look. From what I can tell by consulting the Phantom Wiki, the stories in the King Comics era, including those in this issue, are not all adaptations of published newspaper storylines (notably, the first two King issues, the ones with the Western-style balloon placement are). Perhaps having the book “in-house” allowed King Features Syndicate to be more comfortable with generating all-new Phantom stories, while Western had needed to be working from already-approved plots to avoid the risk of having to reject stories. The first story, “The Girl Phantom”, is loosely inspired by the newspaper strip, which had told a story of the current Phantom’s ancestors, a pair of twins; the boy, “Kit” and his sister, Julie. Stories of how Julie assumed the identity, temporarily, of The Phantom appeared several times, but from my research, it seems this particular plot contradicts what had been recorded in the newspaper version. It opens with the feature’s usual introduction to tales of the current Phantom’s predecessors: The Phantom is in the Skull Cave reading from the massive hand-written tome recording the many exploits of the generations of Phantoms, in this case, reading to his love, Diana Palmer.  The Phantom tells of how one of his ancestors had twin offspring, and while the “real” Phantom was ill, Julie put on her own Phantom costume to give the impression that The Phantom was still out there protecting the jungle. She tries to stay at a distance so that no one will notice her more feminine figure, but when she tumbles from a horse, a couple of goons discover her secret. When Julie fights back ably—she does, after all, have similar training as her brother—the thugs keep quiet, revealing the ruse to their criminal boss, who finds the notion of a “girl Phantom” almost as hilarious as his henchmen being beat up by a woman. Her high level of combat capability leads him to conclude that this must be The Phantom’s sister, and he sees an opportunity to find The Phantom’s headquarters and learn all his secrets, so they set a trap, getting her horse to walk over luminous chemicals which at night reveal a trail right to the Skull Cave. (Somehow the bad guy knows that The Phantom’s hideout is a Skull Cave?!)  Inside the cave, the boys loot generations of gathered treasure and take Julie unawares. They tie her up and run off with the secret books and the treasure. Julie whistles for her leopard, Fury, who frees her, and she trails them, figuring out that they would have followed the luminous hoofprints to find their way back out of the jungle.  Julie finds them escaping down the rapids and hurls a spear attached to a rope, screaming at them to stop. She tries to pull them back by tying the rope to her horse, and they realize too late: Julie was not trying to capture them, but to save them from plunging over the falls just ahead of them. Aside from Julie putting herself down for being an inferior “girl Phantom”, it’s a decent little tale. Next up is a chapter of an ongoing Flash Gordon backup, drawn and inked by Gil Kane. The story is trivial: Flash and a woman he calls “Patch” land on a strange planet when their spaceship is damaged. On the surface, they find themselves hypnotized, following floating balls of light that leads them to a giant monster. The monster eats the glowing balls, Flash heads back to his ship to get a “hydro blast weapon” and kills the monster. They fly off. Seriously, that’s it. I can’t tell whether the balls were hypnotizing them or whether the monster was hypnotizing the balls and the humans, and just preferred eating the glowing ball beings. The self-inked Kane looks much the same as his self-inked work did in the 80’s, but the monster was rather silly-looking, as Kane’s monsters sometimes were. Next, the “real” Phantom appears in “The Invisible Demon.” An invisible enemy is causing terror among a native tribe. The Phantom discovers it’s really an invisible helicopter operated by Dr. Krazz, his “sworn enemy.” Well, actually the son of Dr. Krazz, who died fighting this Phantom’s father, but so far as Krazz Jr. knows, he’s avenging his father’s killer, not the son.  Krazz received the secret of invisibility from a civilization of underground beings known as the Mytors, in a deal that would see Krazz becoming the overlord of Earth once the Krazz had been given enough human samples to research, and thus adapt their own bodies to living above ground. Krazz also has an enlarging ray, to make a giant crocodile to fight The Phantom, but The Phantom fights back, rescues the captured tribesmen, and sics his hound Devil on Krazz Jr. The good guys escape and The Phantom sets off explosives in Krazz’s volcano hideout, ending the Mytor threat and leaving Krazz to face punishment from those with whom he had plotted.  “The Girl Phantom” is attributed to writer Dick Wood and Jerry Siegel, according to the GCD, wrote “The Invisible Demon”. Of the two, the lead story is the better; Siegel’s script may be flashier, but it’s sloppy. I wasn’t even sure from the text whether the Mytors were or were not the tribe of Africans in the beginning of the story. It wasn’t until the final few pages when the mole-like Mytors showed up that I was able to figure it out. This is the Siegel that gave us Mighty Comics, not the one that gave us Superman. It's not really much of a difference from the Gold Key version that immediately preceded King’s run. The young readers of the time probably didn’t remember reading the original versions of the old strip storylines that Gold Key was adapting, so the new storylines King was producing may not have been all that much of a draw. Bill Ligante was still around to maintain continuity of the art style and I suspect whoever was picking this up routinely didn’t perceive a significant change beyond the cover dress, and the presence of the Flash Gordon backup, which gave a bit more of a modern sheen to the look of the comic, but didn’t provide any reading thrills, at least not this installment. The Phantom also appeared in several issues of HARVEY HITS, beginning with its first issue in September 1957. This series headlined random Harvey features, with occasional licensed properties. The Phantom also appeared in issue 6, 12, 15, 36, 44, and 48, but from then on, through its final 122nd issue in November 1967, it was all humor comics, usually spin-offs from existing characters from their Richie Rich, Casper, or Sad Sack titles. For The Phantom’s issues, Joe Simon repackaged newspaper strips, adjusting art for transitions and drawing or commissioning covers like this one:  I consider newspaper reprints outside the purview of my jungle comic book focus, but I did want to acknowledge the presence of this as one of the jungle options available, at least occasionally, to readers of the time. Still to come: The Phantom’s jungle adventures at DC and Marvel. |

|