The Black Island (French:

L'Île noire)

Original publication dates: April 1937 – June 1938

First collected edition: 1938 (partially redrawn colour edition published in 1943; second redrawn colour edition published in 1966)

Author: Hergé

Tintin visits: Belgium (Brussels, Ostend, unidentified village), England (Dover, Eastdown, Beachy Head), Scotland (Kiltoch, the Black Island, Glasgow)

Overall rating:

Plot summary available here

Plot summary available here.

Publisher's synopsis:

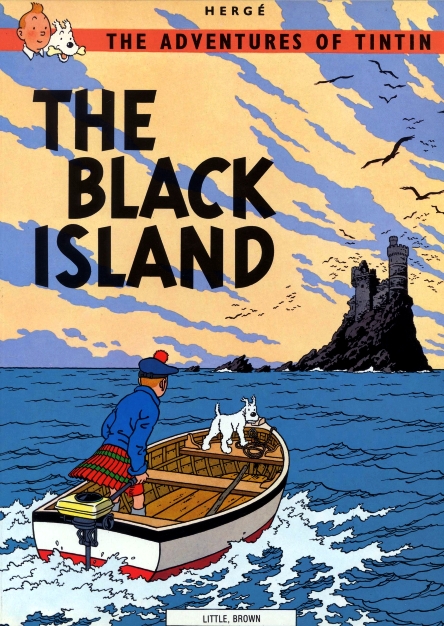

Off the coast of northern Scotland lies the Black Island, its ruined castle a grim warning to intruders. Those who set foot on the rocky shores are never seen again. No one will dare to venture there from Kiltoch. The dark secret must be uncovered, and it is Tintin, the boy reporter, who makes the attempt. A chain of mysterious events leads first to a house in Sussex, then to Scotland to combat the unscrupulous Dr. Müller.Comments:

The Black Island was first published in black and white in the Belgian children's newspaper supplement

Le Petit Vingtième between April 1937 and June 1938. Like many of Hergé's earliest Tintin adventures it was partially redrawn in the standard 62-page colour format in the mid-1940s. For over 20 years, the 1943 colour edition was the version available throughout Europe, but, when it came time for the book to be published in Britain in 1966, Hergé's English publishers, Methuen, requested that parts of it be revised, in order to eliminate instances where the England depicted looked rather outdated. Ever the perfectionist, Hergé sent his assistant, Bob de Moor, to Britain to conduct additional research and take reference photographs. Upon de Moor's return to Brussels, Hergé and his Studios Hergé team completely redrew the adventure for its English publication and it is this commonly available, second colour version from 1966 that I will be basing my review on.

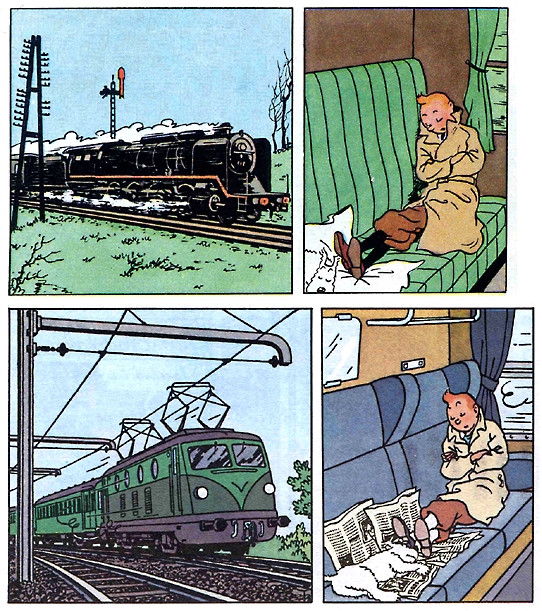

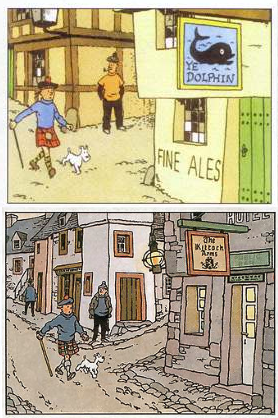

In terms of how the book was updated, a quick Google search has provided me with a couple of panel comparisons between the 1943 and 1966 editions, to illustrate just how much Hergé modernised and refined the story...

As can be seen, not only did Hergé update the vehicles and settings, but he and his team also added a lot of additional detail to each panel. As a result, this story has the look of a classic, late period Tintin adventure like

The Castafiore Emerald and

Flight 714. The motor cars and trains are all of a 1960s vintage, which causes a big jump in period detail between this adventure and the preceding

The Broken Ear. How much this sudden change from the 1940s to the 1960s – and then back again to the '40s for

King Ottokar's Sceptre – will bother you, if you're reading through the series in order, definitely depends on your own tolerance of such things. Personally, I'd be lying if I said that it didn't niggle me at least a little bit.

The Black Island has Tintin travelling to England and then on to Scotland in a gripping detective adventure which sees our hero on the trail of a gang of counterfeiters and a mysterious monster. The book is, for all intents and purposes, "

Tintin in Britain" and it represents the only time that we see the boy reporter visiting "this sceptred isle" (although

Flight 714 does have Tintin flying into Java from London, so he obviously visited England again, even though we don't actually see him there).

Without doubt, a lot of my fondness for

The Black Island stems from the fact that it's a real kick to see Tintin visiting my home country. Hergé, with help from his studio team, really does a fantastic job of conjuring an authentic looking, mid-60s version of South England. I was raised in semi-rural South East England and Hergé's depiction of this part of the country really looks very close to the England I remember as a child in the late '70s. The cars, trains, villages, roads and police constables all look very familiar to me in a hazy, nostalgic way. In particular, there's a panel of Tintin passing by an old black & white British road sign on page 11 that I love because, although most of these signs have today been replaced by ugly, reflective aluminium ones, there are still some examples of this old style signpost in the villages just a few miles from my house...

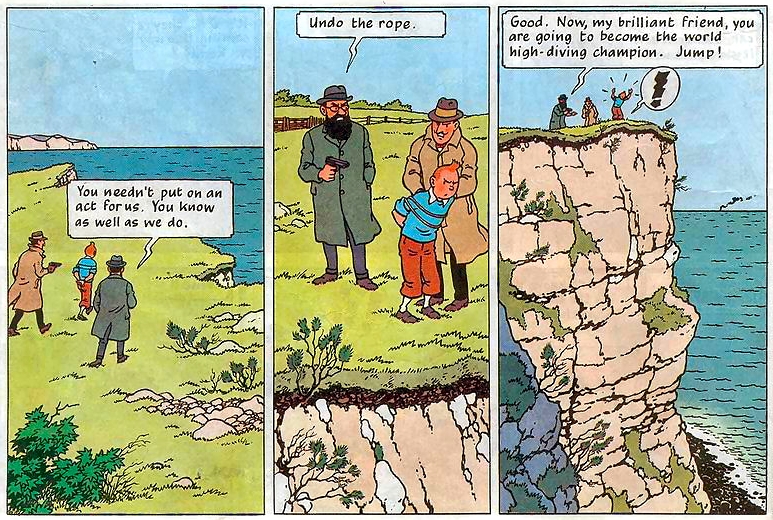

The early part of Tintin's British adventure begins in the county of Sussex, where our hero visits the town of Eastdown, which is perhaps based on Eastbourne? He also almost gets killed when the counterfeiting gang attempt to force him off Beachy Head cliff, which is a notorious spot for suicides here in England...

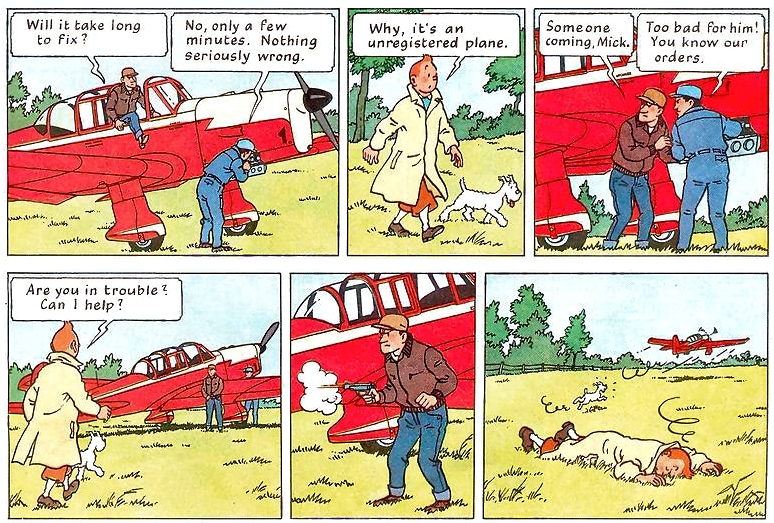

Prior to his arrival in the UK though, the story opens in Belgium in truly dramatic fashion, with our hero getting gunned down on the opening page! Luckily for the boy, it's only a graze, and he wakes up in hospital sometime later and discharges himself (the first of two instances of him doing this in the story), proving that he's obviously very fit. I can definitely recall how shocked I was as a child to see our hero seemingly shot dead on the opening page of the book, and it's certainly a dramatic way to start the adventure!

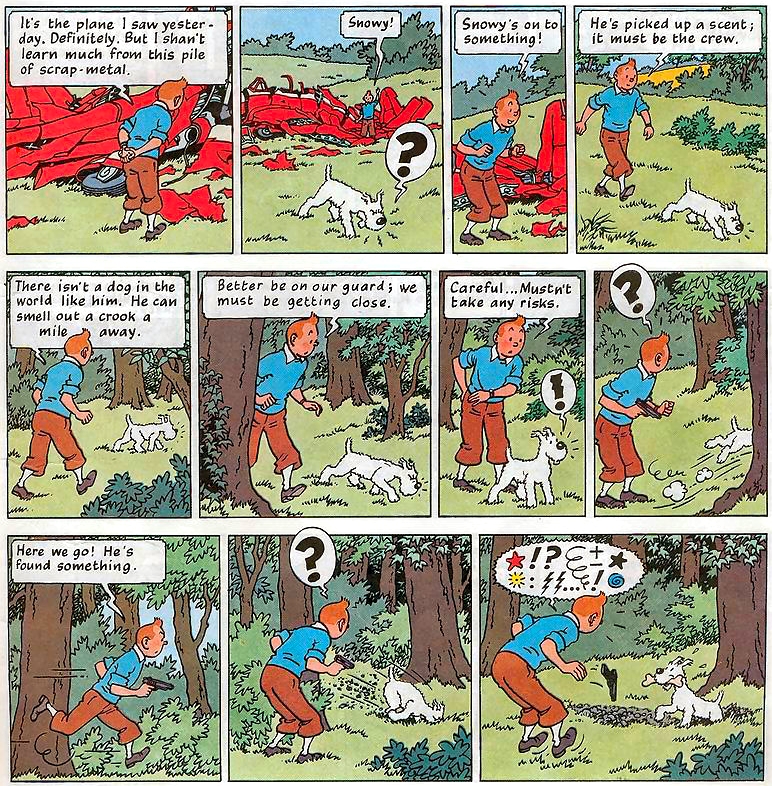

The red aircraft carrying the would-be assassins is traced to Sussex, where it crashes, and that's how Tintin finds himself in southern England. Actually, there's a really humorous scene involving Snowy, as the boy reporter and his dog locate the wreckage of the plane; Snowy goes off sniffing and hunting for what Tintin believes are clues, but which actually turns out to be an old bone!

This scene always makes me laugh and will no doubt strike a chord with many a dog owner.

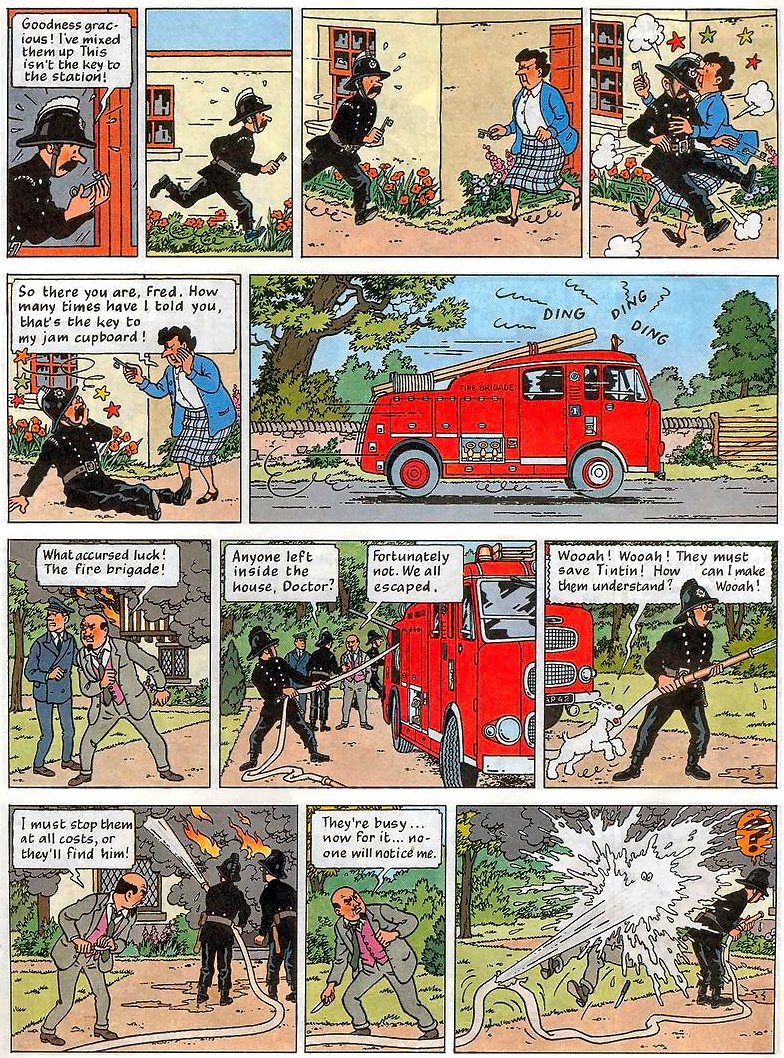

Actually, there's lots of humour in

The Black Island, with much of it being rather more farce-based than we are used to in the series. A good example of this farcical comedy involves the Eastdown Fire Brigade, who must be the world's most ineffectual fire fighting team. In fact, they appear to be more like the Keystone Cops than a serious fire and rescue service...

While I do find the fire brigade's antics to be highly entertaining, I must say that their scene serves as a slightly unwelcome distraction to the ongoing plot, since it slows down the pace of the story at this point considerably and kills some of the tension associated with Tintin's deadly confrontation with the mysterious Dr. Müller. Likewise, the scene later on in the book where the Thom(p)son Twins' hopelessly out of control aircraft gets caught up in an air show is very entertaining, but it does break the momentum of the story a little bit. Hergé also stretches credibility somewhat when the Thom(p)sons eventually land in Scotland, having been flying in their tiny two-seater plane for over 24 hours without refuelling!

Actually, while we're on the subject of the Thom(p)son Twins, this is the first Tintin adventure in which they really get a chance to shine. Their part in the story is sizeable and they are right there, trailing just behind the boy reporter, for pretty much the whole book.

Snowy also really shines in this adventure, with

The Black Island being arguably the story in which the little terrier plays the biggest part. Hergé gives the dog lots of character and shows what an asset he is to our hero, by having him save Tintin from a number of near death situations, such as a burning building and the counterfeiter's attempt to push him off of a cliff.

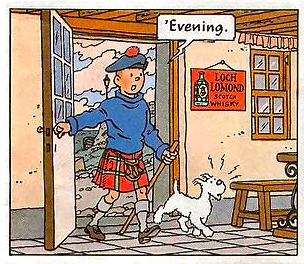

Incidentally, on page 33, Tintin and Snowy hitch a ride on a freight train that is carrying Loch Lomand whisky, which, later on in the series, we will find out is Captain Haddock's favourite tipple. Originally, the freight container was carrying a different brand of whiskey, but when he drew the 1966 edition, Hergé obviously wanted to insert a little reference to the Captain, retroactively making this the first chronological mention of the whisky in the series.

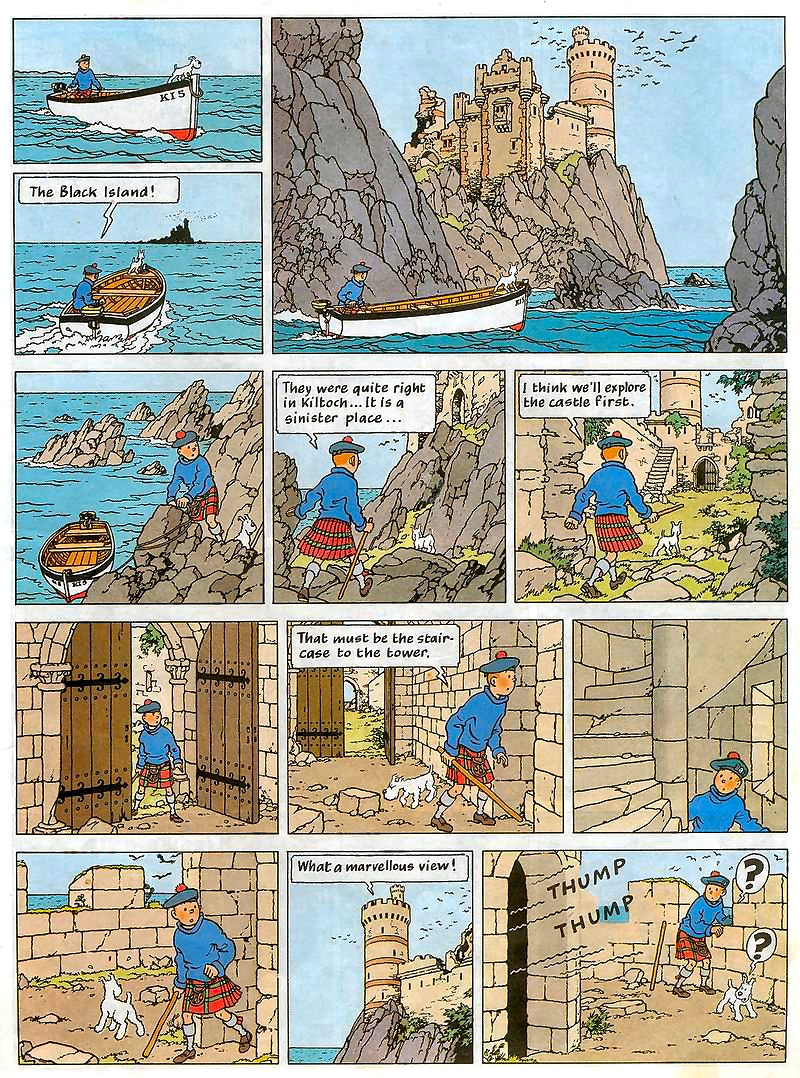

Once Tintin has arrived in Scotland and the village of Kiltoch, Hergé ramps up the mystery, with a masterful build up of tension, as the boy reporter hears ominous tales from the locals of "the beast" that supposedly lurks on the nearby island. Oh, and, of course, just like when Tintin has visited other countries, he has to don the national dress...

The story grows ever more suspenseful and gripping as Tintin approaches the deserted castle in a small boat, with the artwork in this part of the story conjuring a superbly sinister and foreboding atmosphere, as Tintin ties up his boat and begins to explore the ruined fortress...

The mysterious beast lurking within the ruined castle on the Black Island turns out to be a monstrous gorilla, which Wikipedia tells me was inspired by the classic monster movie

King Kong, which had been released in 1933. I love that Ranko, the gorilla, is afraid of little Snowy and is tamed by the terrier's angry bark, much like the lion in

Tintin in the Congo was. Then, in a deliciously comedic twist, we see that the "ferocious" Snowy is himself scared of a tiny spider on the floor!

The artwork in

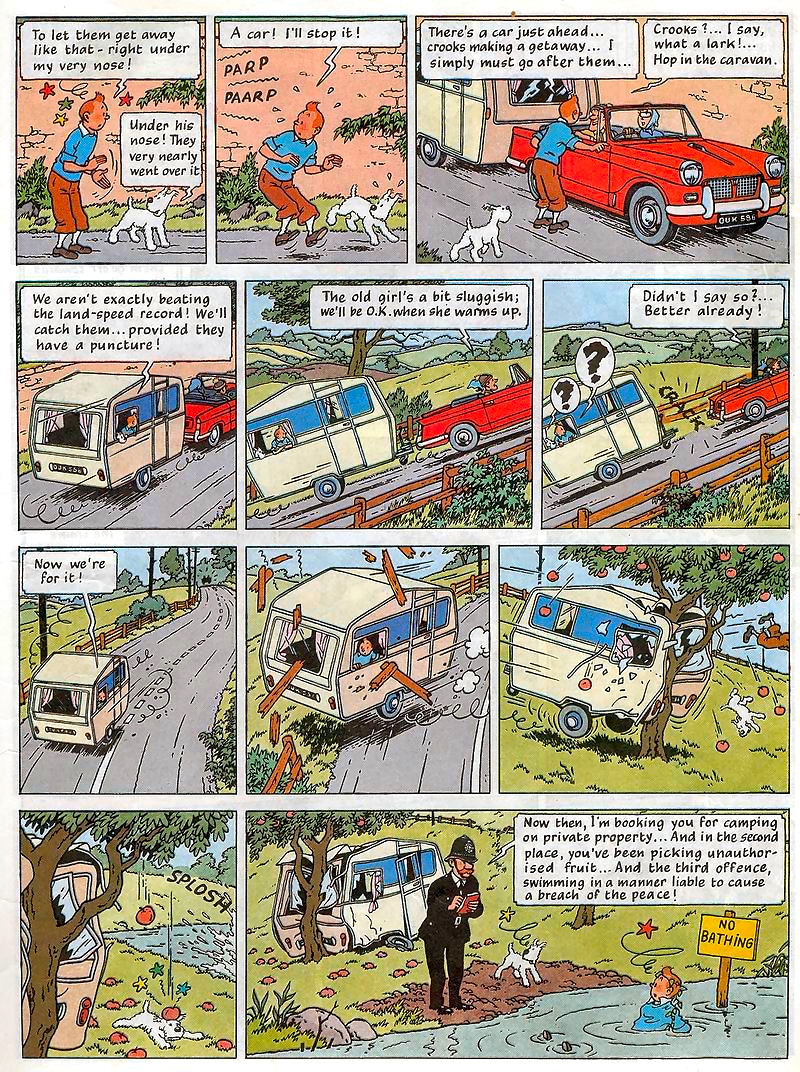

The Black Island is very, very good indeed. Stunningly good, in fact! There's an abundance of gorgeous detail and Hergé's intuitive way with sequential art ensures that every scene works superbly – especially the parts reliant on physical comedy. Just take a look at the dynamic "stunts" and comedic energy of this scene involving a holiday caravan...

Artistically,

The Black Island really is a classic example of Hergé and his studio team firing on all cylinders and, as a result, it's an absolute joy to behold. Nevertheless, I have seen some Tintin fans online saying that they prefer the artwork in the original 1943 version of the book. Their complaint being that, with its strict attention to accuracy and increased emphasis on detail, the art in the redrawn version is overly fussy, when compared to the first colour edition. I can sort of see what they're saying – not that I've ever read the original 1943 edition, mind you, but I've certainly seen enough of it online to form some kind of opinion – but, for me, the heightened detailing doesn't in any way detract from the momentum of the story and it's such a pleasure to cast your eye over the art that complaints of it being "fussy" are, to me mind, simply nitpicking.

Overall,

The Black Island is one of my absolute favourite Tintin stories. The "new", mid-60s artwork is very good and highly polished, with plenty of fascinating detail in which to lose yourself as you read. The book is a pulpy, detective-style thriller, that is, at once, firmly routed in the 1930s, while simultaneously looking like the 1960s, but nevertheless being a strangely timeless read.

The Black Island might be less serious and political than

The Blue Lotus, but it also might actually be a better overall read precisely for that reason. Certainly it's the more enjoyable of the two books, as far as I'm concerned.