King Ottokar's Sceptre (French:

Le Sceptre d'Ottokar)

Original publication dates: August 1938 – August 1939

First collected edition: 1939 (partially redrawn colour edition published in 1947)

Author: Hergé

Tintin visits: Belgium (Brussels), Germany (Frankfurt), Czech Republic (Prague), Syldavia (unidentified villages, Klow), Borduria.

Overall rating:

Plot summary available here

Plot summary available here.

Publisher's synopsis:

When Tintin and Snowy travel to Syldavia with Professor Alembick, they find themselves mixed up in a rebel plot to depose the Syldavian king. If the king does not carry King Ottokar's sceptre in the royal procession he will lose his throne, and when the rebels manage to steal the sceptre the detectives Thomson and Thompson are called in. Tintin and Snowy must act fast before it's too late for the king, and possibly themselves.Comments:

King Ottokar's Sceptre was initially published in the pages of the Belgian children's newspaper supplement

Le Petit Vingtième between 1938 and 1939, and was then redrawn by Hergé and his assistant Edgar P. Jacobs in the standard 62-page colour format in 1947.

The story holds a special distinction among The Adventures of Tintin, in that it was the first of the stories to be translated into English, when it appeared as a serial in the iconic British boy's comic, the

Eagle, in 1951. On that occasion, the story was translated by a professional Belgian interpreter whose name is now sadly lost to time. Interestingly, in this earliest English version, Snowy retains his Belgian name of Milou, while the bumbling detectives Dupond and Dupont are renamed Thomson and Thompson for the very first time. The "Thom(p)son" moniker was retained for the detectives by the series' official English translators, Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper and Michael Turner, when the Tintin books were translated by them. The commonly available English translation of

King Ottokar's Sceptre that you will find in shops today was translated by Lonsdale-Cooper and Turner when the book was published by Methuen in 1958, and it is this commonly available version that I will base my review on.

The first thing I want to mention is the book's cover. It's a striking image of Tintin and Snowy striding out through the portcullis of Kropow Castle in Klow, Syldavia, while two splendidly attired guards look on. As some of you may recall from my earlier reviews, I first encountered the Tintin books at my local library, and, as such, it wasn't always possible to borrow a particular book – you had to wait until it wasn't out on loan. The back of each book had illustrations of all the other volumes in the series and the cover of

King Ottokar's Sceptre always stood out to me and looked especially intriguing. Unfortunately, it proved to be quite elusive and I recall how frustrating it was as a young lad trying to track it down and check it out.

The story itself begins in Brussels, where Tintin finds a briefcase on a park bench, which leads him on an adventure to the fictional Balkan country of Syldavia. There, Tintin discovers a plot to force the Syldavian monarch, King Muskar XII, to abdicate, in order to facilitate an invasion of the country by the neighbouring fascist state of Borduria. This invasion is orchestrated by the Bordurian politician Müsstler and there's little doubt that the story is a none-to-thinly veiled commentary on, or satire of, Nazi Germany's annexation of Austria in March 1938. No doubt the vulnerability of tiny Belgium against Nazi Germany would have been weighing heavily on Hergé's mind at the time he worked on this adventure and, indeed, the author later admitted that Müsstler was directly inspired by, and named after, Hitler and Mussolini.

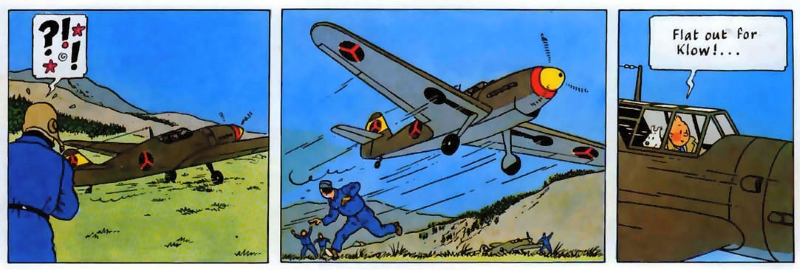

At one point in the story, after sneaking across the Bordurian border, Tintin steals a Messerschmitt 109, complete with Nazi-style emblems on its fuselage and underwings, further reinforcing the parallels between Borduria and Nazi Germany...

I kind of wonder what the Nazi's thought of this story when they invaded Belgium, but I guess they probably had bigger fish to fry than worrying about a children's newspaper comic strip. Although, having said that,

Le Petit Vingtième and its parent publication

Le Vingtième Siècle were both shut down, and

The Black Island and

Tintin in America were banned (due to their being set in Allied countries), when the Germans invaded in May 1940. So, the Nazi censors were certainly aware of the Tintin strip.

I must say, although it's a fictional country, Syldavia feels utterly authentic. The region is clearly implied to be in the Balkans and, having visited the Balkan countries of Macedonia, Albania and Bulgaria a few times back in the late 1990s, Syldavia certainly reminds me of that region. For example, the below panel depicts a village that looks very much like the ones I visited along the Macedonian and Bulgarian border...

Likewise, I remember seeing woodland areas in Macedonia that looked very much like these beautifully drawn panels...

At one point, Tintin reads a Syldavian travel brochure – whole pages of which are reproduced in the book itself for the reader to peruse. This functions as a clever way to impart lots of historical context and background information about the fictional country to the reader and is a really inventive touch. I think Hergé must have been pleased with the authenticity of his fictional location because he would return to Syldavia in the books

Destination Moon,

Explorers on the Moon, and

The Calculus Affair.

One little detail that does jar with me in this story is how, early on in the adventure, the villains haven't heard of Tintin and seem to know nothing of his reputation as a detective. In earlier adventures, we've seen that the boy reporter's fame has spread as far afield as Africa and China, but these criminals (who are residing in Brussels!) have seemingly never heard of him!

There's a particularly noteworthy introduction in

King Ottokar's Sceptre with the first appearance of the opera singer Bianca Castafiore, the "Milanese Nightingale", whose painfully piercing voice becomes a great source of comedy as the series progresses. Castafiore is important for being the only recurring female supporting character in The Adventures of Tintin, and she is very much a comedic creation. She will become a particular aggravation to Captain Haddock, who will be introduced in the next adventure. The well-intentioned opera singer's main character traits are vanity, garrulousness and her utter lack of awareness concerning the appalling shrillness of her voice. Right from Tintin's first meeting with her, Castafiore's voice is loud and painful enough to send men cowering and animals running in all directions...

I think it's safe to assume that Hergé wasn't a fan of opera!

Incidentally, note how, in the above panels, the car's window displays the British Standards' "Kite Mark" of safety. I have to assume that this emblem was inserted into the artwork specifically for the British publication of the adventure in 1958. Surely in other, non-English versions, this panel would feature a different safety symbol on the car window? Can

Roquefort Raider or anyone else confirm this?

While we're on the subject of the art, Hergé's work is of the usual high standard, but there is a noticeable lack of detail, when compared to the re-drawn version of

The Black Island that, to anyone reading the series in order, precedes

King Ottokar's Sceptre. As I noted in my review of

The Black Island, that book was re-drawn in 1966 and consequently has the look of a late period Tintin adventure, while

King Ottokar's Sceptre looks much more like mid-50's Hergé. Basically, we've been spoiled by

The Black Island and the art in this adventure suffers slightly by comparison.

Still, there's plenty of excellent cartooning on display here, with this gorgeous sequence, in which Tintin pursues a conspirator to the Syldavia–Borduria border, being a particular favourite of mine...

Like an awful lot of the artwork in this book, there's plenty of movement in the above panels, as Hergé effortlessly leads the reader's eye from dynamic panel to dynamic panel. The kinetic quality of the artwork really comes into its own during some of the book's more slapstick and physically comedic moments, such as when the Thom(p)sons attempt to demonstrate their theory about how thieves threw Ottokar's sceptre through the barred windows of the royal treasury. This hilarious sequence never fails to have me in stiches...

I don't know about you, but I can practically "see" and "hear" that branch bouncing off of the window bars and hitting poor Thompson in the face.

In a decidedly Hitchcockian move, Hergé drops in a sneaky cameo of himself and his assistant, Edgar P. Jacobs, during the concert given by Castafiore at the royal palace (on the far left of this panel)...

Overall, I'd have to say that the humour in this adventure is slightly less farce-based than in the previous one, but there's still plenty of laughs to be had. The Thom(p)son Twins, in particular, are funnier than ever in this book. Hergé even recycles a gag from

Cigars of the Pharaoh on page 13, when he has the two detectives fall off the back of a motorcycle as it pulls away.

Snowy has plenty to do in this adventure too, and there's a lovely moment on page 34 where the faithful terrier steals a giant bone from a dinosaur exhibit at the Natural History Museum in Klow, before losing possession of it to a pack of stray dogs. We also get a charming sequence in which the dog – who has picked up the royal sceptre, after Tintin accidentally dropped it – is tempted by a bone lying on the road. Unable to carry both the sceptre and the bone, we see the dog's internal dilemma and just how tempted he is by that delicious-looking bone. Ultimately, knowing how much his master would disprove of him leaving the sceptre, Snowy dutifully does the right thing and saves the day...

Another humorous – although simultaneously quite dark – moment occurs when Tintin and his faithful terrier enter a Syldavian restaurant, as part of their investigations. The young lad gets a shock when he momentarily thinks that he may've just eaten Snowy!

Of course, Snowy had simply been helping himself to some grub in the restaurant's kitchen. Let's just hope he didn't accidentally eat any dog while he was in there!

All in all,

King Ottokar's Sceptre is a really enjoyable book that is equal parts gripping espionage thriller, pointed political satire, and palace detective yarn – with an utterly intriguing locked-room mystery at its core. Of course, Hergé had flavoured his Tintin stories with the spice of real world politics before – most notably in

The Blue Lotus – but here there's a new sense of maturity to the authors' geopolitical commentary, very much capturing the sense of paranoia and foreboding in Europe on the eve of the Second World War. The introduction of Bianca Castafiore to the supporting cast is highly significant, within the context of the series, and we also get a dry run for the character of Professor Calculus (who will appear in

Red Rackham's Treasure) in the shape of Professor Alembick. Although the art isn't quite up to the impossibly high standards of the previous book, this is another very high quality Tintin story, which, perhaps more than most in the series, feels very much rooted in a particular time period.