To add to Farrar's excellent information re

The Brave and the Bold... This is

"reprinted" from an old thread of mine that you can find here:https://classiccomics.org/search/results?captcha_id=captcha_search&who_at_least_one=80&what_exact_phrase=+Brave+and+the+Bold&where_thread_title=Comic+Lover%27s+Memories&when_between_start=04%2F01%2F2014&when_between_end=12%2F12%2F2022&display_as=0&search=Search

Let’s get this out there before we go too much further and you can decide whether or not you want to stay.

I am nerdy.

As if posting this kind of stuff on this kind of forum weren’t enough of an indication.

There’s far more to the story.

Crossword puzzles.

Reading books about nearly anything.

White socks.

Cardigans.

English teacher.

Shakespeare nut.

I think that’s enough. If I say too much, I may be put on “Ignore” by everybody.

So, fair warning, and welcome to the Pequod.

In my obsessive desire to find out why The Brave and the Bold might have been given such a distinctive, “un-comicy” name, I decided to check into two areas: literature and popular culture.

(Oh, and don’t worry, to avoid the infamous “purloined letter syndrome,” I looked for any clues in the early issues. There were none. Kanigher ran text pages and humorous cartoons as fillers; there were no letters pages or Editor’s Notes.))

I’ll spare you the details of the research and boil down my findings.

I first wondered if there might have been an earlier story, poem or novel that might have been the source.

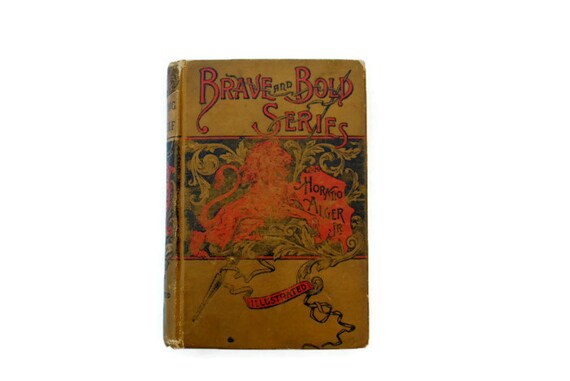

In 1872 the iconic author, Horatio Alger, wrote a novel (first serialized in the New York Weekly, called Brave and Bold.

Here’s a synopsis, if you’re interested, courtesy Pavilion Press, which publishes Alger reprints.

(Hope that kid is faster than that speeding locomotive!)

www.pavilionpress.com/products/Brave-and-Bold--by-Horatio-Alger.htmlWell, I thought, this is an interesting coincidence, but it’s far from proof that anyone at DC involved in the creation of B and B might have read this book as a kid.

It was Robert Kanigher who was tasked with coming up with a comic book in those days of falling superhero sales and the spectre of Dr. Wertham.

Might Kanigher have read that particular book, or just seen the title and filed it away when he was a kid? He was a New York kid, born in 1915, described himself as quite the reader. A new edition of Alger’s Brave and Bold came out in 1911, so it’s clear the book was still in some demand. No doubt it was stocked in the New York public libraries, which we can assume Kanigher frequented. (He was already a published writer as a teenager.)

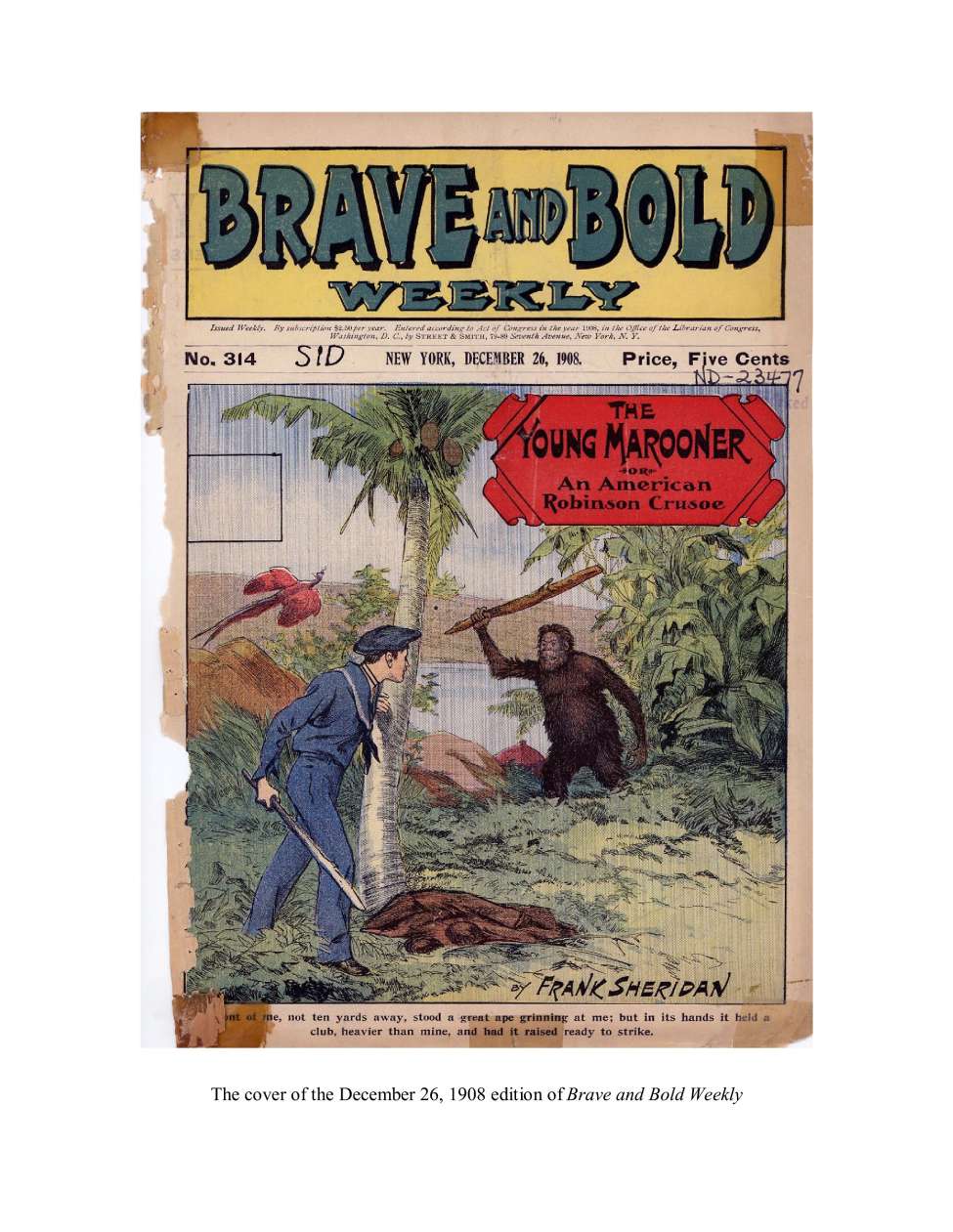

Less likely is that Kanigher saw any of the 429 issues of a weekly magazine (more properly a series of dime novels) published by Street and Smith from December 1902 through March 1911, devoted to reprints of adventure stories from previous Street and Smith magazines, like “The Young Marooner” (1908) by Edgar Rice Burroughs. The magazine was called was called Brave and Bold Weekly. (Maybe Street and Smith cribbed their title from Horatio Alger?)

This one has an unfurling banner, too, as quite a few of these covers did... Hmmmm.

Perhaps it’s possible that Kanigher knew of Brave and Bold Weekly. It’s not difficult to imagine that old issues might float around, passed from friend to friend or even treasured for a while by a young reader and then given away or tossed aside. I’m not sure a library would have stocked this sort of entertainment for its younger clientele, but maybe.

Later, some of Alger's books were sold in collected editions, called...

Medieval style there, isn't it? Hmmmm.

Might Kanigher have read these as a kid? Hmmm.

There was also an adventure movie in 1918 called Brave and Bold about a kidnapped war contractor, based on a scenario by Perley Poore Sheeran, who write stories and novels like those of Edgar Rice Burroughs (Kwa was his jungle guy and Captain Trouble one of his adventurous types.) as well as others in the horror and fantasy genres. Kanigher was only 3 when it was released, but maybe it was re-released and he caught it when he was older?

Now here’s another possibility for the phrase sticking in Kanigher’s young and receptive mind: “K-K-K-Katy,” the popular World War One (and World War Two, also) song...

whose very first verse reads,

“Jimmy was a soldier brave and bold,

Katy was a maid with hair of gold…”

Did the old song lyric stick with Kanigher?

Or had he read it as a school kid in New York, in the days when poetry was a much more important part of the curriculum from elementary school right through high school and college?

The phrase pops up here and there.

I thought maybe that the pairing of the words “brave” and “bold” had occurred somewhere in a poem or novel that someone of Kanigher’s age might have been exposed to, just as pairs of words like “cloak and dagger” (thanks, Charles Dickens) and “Stars and Stripes” (first used 1809) appear somewhere first and then become part of the lexicon.

Shakespeare (I had to check) used the two words in close proximity three times: in Henry IV, 2; in Henry VIII; and in his long poem “The Rape of Lucrece.” But never did he write it as the expression, “the brave and the bold.”

The earliest pairing of the two words I could find was in a poem in 1660:

“The Polish Nose is brave and bold,

And the Russes Nose is oft a cold.”

Doubt this was Kanigher’s inspiration.

But wait, there's more!

“He who is both brave and bold

Wins the lady that he would..."

Vicente Espinel wrote this in a Spanish poem in 1591 and I didn’t think it would be a likely candidate, either, but the name of the poem is “Faint Heart Never Won Fair Lady,” and I think, even from a quick check, that there's a good chance that the poem was widely anthologized. (I’m sure the English translator was loose with his translation of whatever Espinal’s title was in Spanish; the maxim goes way way back…)

“Honour rewards the brave and bold alone…” wrote Robert Lowth in “The Choice of Hercules,” published in 1743.

Tacitus wrote, “The brave and bold persist even against fortune; the timid and cowardly rush to despair through fear alone.”

And here’s one from Henry Ward Beecher: “No land ever, even in war, did so brave and bold a thing as to take from the plantation a million black men who could not read the Constitution or the spelling-book, and who could hardly tell one hand from the other, and permit them to vote, in the sublime faith that liberty, which makes a man competent to vote, would render him fit to discharge the duties of the voter. And I beg to say, as I am bound to say, that when this one million unwashed black men came to vote, though much disturbance occurred—as much disturbance always occurs upon great changes—they proved themselves worthy of the trust that had been confided to them.”

I don’t know if Kanigher would have been exposed to any of these works in school, but when I get obsessive, I say, “Leave no source unexplored!”

(That's the war-cry of the nerdy, by the way.)

And even if Kanigher had never run into any of these in school, I wouldn’t discount that he may have encountered them on his own. In an interview he gave to The Comics Journal back in 1982, Kanigher refers to Petronius (author of the Satyricon), Van Gogh, Gustave Doré Aubrey Beardsley and El Greco. He even alludes to Shakespeare’s As You Like It when he off-handedly describes a previous interviewer as “the lad with shining morning face.”

Clearly Kanigher was well read and absorbed what he read and was well acquainted with more than war comics. His wife was a NYC school principal, and his daughter took dance lessons at Julliard. This was not an unsophisticated man.

All right, got the pseudo-scholarly stuff out of the way.

On to popular culture.

According to the indispensable Mike, proprietor of Mike’s Amazing World (Saints and devils be praised!), the first issue of The Brave and the Bold appeared on newsstands on June 7, 1955.

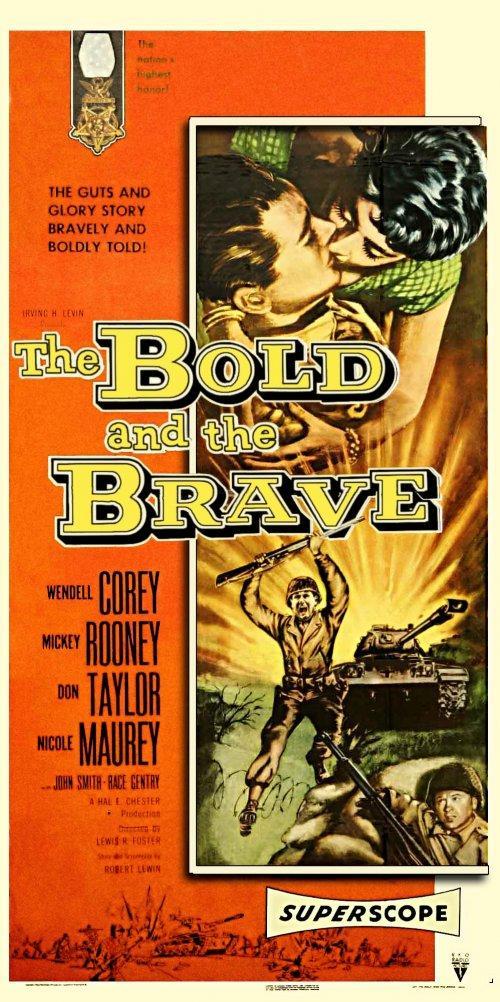

Less than a year later, in April 1956, a movie was released called The Bold and the Brave, a World War Two movie starring Mickey Rooney.

It was based on an original screenplay by Robert Lewin, who was nominated for an Oscar for it and later wound up writing for a jillion TV series, from The Munsters and Mission: Impossible to Star Trek: TNG, for which he also served as a producer with Gene Roddenberry.

Might Kanigher have heard about that movie being in preparation and liked the title?

We-e-e-e-ll, maybe. Then again, maybe Lewin or one of the movie’s producers saw a copy of the comic on the stands and liked the title…

Nothing either way here.

One last try:

From 1948-1957, The Philco-Goodyear Television Playhouse, one of early television’s landmark series, presented every Sunday night at 9 on NBC, live performances of classics like Cyrano and Othello and original productions, like What Makes Sammy Run and Marty. Featuring a roster of Hall of Fame directors, actors and writers, the show was one of the reasons that era is still referred to as the Golden Age of Television. Among the famous and soon-to-be famous who contributed to its success: Grace Kelly, Rod Steiger, Walter Matthau, Jose Ferrer, Steve McQueen, Arthur Penn, Delbert Mann, Paddy Chayevsky, Gore Vidal, and Horton Foote.

This would have been appointment television when there was no other option.

On Sunday, April 17, 1955, Philco presented an original teleplay (as it would have been called then) by Calder Willingham, who would later write the screenplays for such films as Little Big Man, The Graduate (with Buck Henry), One-Eyed Jacks, and Paths of Glory. Not too shabby.

Willingham’s story was set at a military school and centered on the conflict between an overly demanding commander and his son, a student at the school. Years earlier, some of its elements were contained in Willingham's novel,

and later became a part of the film

However, this version of the story was entitled “The Bold and the Brave.”

Is it possible that the very literate Kanigher saw this episode? Sure.

Is it possible that he liked the title, altered it a tad and used it as the title for the new comic that DC intended to hit the stands in less than a month? Sure.

But, would there have been enough time for him to have either replaced a previously created title or have at last found the title he wanted for the new book?

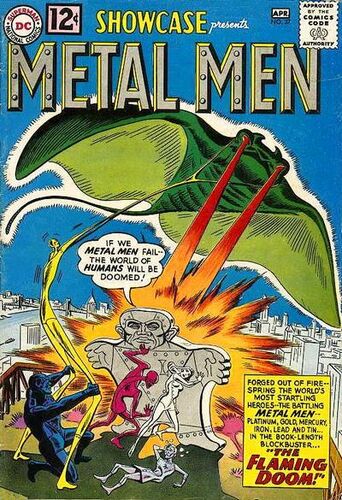

I’m going with possibly, especially given Kanigher’s part in the legendary creation of Showcase #37, a story frequently recounted.

For those who may not know, Kanigher was “volun-told” to produce a new feature 14 days before Showcase 37 was to hit the stands (Jan 30, 1962). Kanigher’s story is that he wrote it the next day after dropping off his daughter at Julliard for her dance class. Long story short, he, Ross Andru and Mike Esposito brought the Metal Men to life in 10 days.

Even allowing for exaggeration, it seems clear that a comic’s title and logo could be created and/or changed in the nearly two months between that episode of Philco Playhouse and B and B#1’s arrival on the stands.

Your mileage may vary, but I’m thinking that there’s at least a strong possibility that the program may have made an impression on Kanigher and that a quick switch in the word order, to avoid charges of plagiarism and to feed his (ample) ego, may have been the source of this uniquely titled comic.

End of lecture for this week's class in "Even Too Nerdy for Comics Fans."